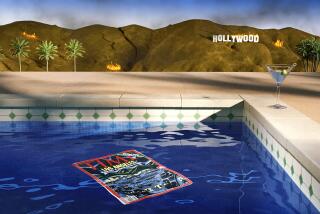

KING CASE AFTERMATH: A CITY IN CRISIS : Violence Colors the Ways Blacks, Whites Interact : Racial relations: Anglos and African-Americans say the images from the streets have caused something profound to happen between them.

- Share via

Blacks and whites together. Has the eruption of violence in Los Angeles altered the way people of different races deal with one another?

Yes, said Kate Rubin, a 33-year-old law clerk who was riding in an elevator Thursday night with a primly dressed black woman leaving work in a Woodland Hills office tower.

“I wanted to say hello,” Rubin said. But she was hesitant because she remembered the hostility between racial groups after the riots in her hometown of Detroit in 1967.

She finally did so anyway, and the other woman nearly broke down in gratitude.

“I’m so glad you talked to me,” the woman said. She told Rubin that the white people in her office had not talked to her all day. She thought they were worried that she might defend the rioting, even though she thought it was as crazy and wrong as anyone. The woman was so upset, she said, that she couldn’t go home. She planned to spend the night at a friend’s house.

The conversation made Rubin feel a lot better too. When the elevator reached the floor level, both women thanked each other for talking and said goodby.

But that wasn’t the end of it. Rubin went to an electronic bank machine to withdraw money. A black man was in line. Rubin couldn’t help noticing the way everyone else kept looking at him, sidelong.

“There’s just such a sense of anxiety and distrust out there now,” Rubin said.

Something profound has happened, both whites and blacks agreed as they shared beers in San Fernando Valley restaurants, stocked up on goods and conducted the myriad other small business dealings that bring people together in public settings.

Just what it will mean over time and how it will change lives is still not clear. The events have not sunk in far enough. The images, one man said, are still in our eyes and not yet part of our selves.

There was fear, however, that the pictures of wanton destruction would tug apart the tendrils of understanding and mutual cooperation that have grown over nearly three decades since the Watts riots. Already, as Rubin saw, there is fertile ground for anxiety and suspicion.

“There is a difference in perception between blacks and whites,” Ricardo Starks, 44, a black real estate broker from Studio City, said Friday as he sat alone and drank a beer at Zach’s Italian Cafe.

“If you’re not raised white, you can’t understand white values,” he said. “If you’re not raised black, you can’t understand black values.”

That, he said, is why the two groups must continue to talk; otherwise, they will never reach common understandings.

In the first hours after the violence began Wednesday in South Los Angeles, one thing had changed in the hip little clubs along Ventura Boulevard that offer late-night meals and soft jazz. There were no black faces in the audience as small combos played at the Baked Potato and La Ve Lee, which are usually filled with a relaxed, mixed-race crowd.

On Thursday night, the clubs were closed. A dusk-to-dawn curfew had taken effect. The empty streets gave an eerie, after-the-apocalypse feeling to the usually choked boulevard. A small and hearty crowd formed at Jerry’s Famous Deli in Studio City, despite the occasional blasts from police loudspeakers ordering, “Get off the streets.”

Charles Grimes, 45, of North Hollywood, who is black, sat watching riot reports on a big-screen television in the bar with his friend, Don Segura, 48.

“I was in the ’65 riots,” Grimes said. “I think this is wrong. We’re burning down our own community. Twenty-five years to get where we are now, and in two days it’s gone.”

Just then, a television station broadcast a report about a white motorcyclist who was shot and killed by rioters in Long Beach.

“See? This is what I mean.” Grimes said. “It’s not worth it.”

His friend, Segura, chimed in, offering an explanation for the violence Grimes was denouncing. It was as if the two men were so eager to find common ground that they had reversed roles.

“The real problem is the economy,” Segura said. “When black people can make what I make, we’ll get over this.”

The two men said they both shared a belief about what was wrong in America and confidence that they knew what it was: bad juries and aimless violence. Their skin colors were irrelevant, they said.

Skin color matters, said Tasha Houlihan, 33, who is black. Despite the curfew, she was keeping the Happy Mart store she owns with her white husband open late.

“I haven’t gotten the impression” people are looking at her differently, she said.

She and her husband are in agreement that prejudice in America still exists, despite improvement in race relations over the years. She complained bitterly that the King case verdicts were the last straw in a chain of events that she traced to the fatal shooting of a black teen-ager by an Asian grocer. Then she said she would be working late that night to protect her Asian clerk from any looters who might come in.

“You’ve got to take people one-on-one” and not judge entire groups, said Starks, the real estate broker.

One of the other women in his office is Korean, he said, describing an argument they had about the grocery shooting. “My Korean friend told me children don’t talk back to adults in Korea,” he said.

That opened his eyes. Then he described his view of the incident, how you just can’t shoot somebody for talking back. “You may be right,” she said. They have become close.

“Racism affects everybody,” he said. Then he paused over his beer. “It will be interesting to see where we are in 2000.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.