Tapes Tell a Tale of Japanese Teachers’ Lessons for Americans

- Share via

As part of the Third International Math and Science Study, the first results of which were released last year, UCLA psychology professor James Stigler conducted the first-ever extensive video survey of math teachers in Germany, Japan and the United States.

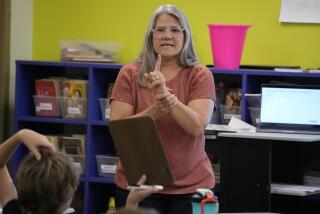

By videotaping classrooms, Stigler and his colleagues were able to describe how lessons differ from country to country. He discussed some of his insights with a gathering of legislators, professors and administrators convened by California State University’s Institute for Education Reform. Asked how the American approach to lesson planning differed from that of the Japanese, he said:

“I once asked a group of American teachers to create a lesson plan. They took 15 minutes to do it. I asked them: ‘Is this all the time you need?’ and they said, ‘Yes, we’ve planned it all out. First we’re going to do this, and then we’re going to do this and then this.’ The American plans always say what the teacher is going to do. The Japanese plans ask what the students are going to think if the teacher does this. If they think A, then the teacher’s next step should be X. If they think B, then the next step should be Y and so on.

“Then I asked one of the American teachers to teach the lesson, and we all went to watch. It was a complete disaster; everything went wrong. Then I asked them to revise the lesson, and this time it took them two months. Suddenly, after having had the opportunity to watch the lesson unfold in the classroom--and later, to review a tape of it--they found it wasn’t a stretch at all to spend eight weeks, two hours a week, figuring out what the lesson’s flaws were and determining the best ways to fix them. We ended up going through the test-teaching-and-revision process twice more.

“The culture issue here is that American teachers don’t have any experience jointly talking about instruction. When they get together, they don’t talk about lessons. They talk about all manner of other professional and personal issues, but almost never discuss how they actually teach their students. Japanese teachers, on the other hand, have a very theoretical approach to teaching. They are very practiced at going through and analyzing a lesson. Furthermore, they have a common research literature, so that when a teacher goes to plan a lesson, he or she has a very good idea what the probable outcomes of posing a particular problem are. The emphasis on invention and forcing students to think problems through in Japanese classrooms really isn’t a matter of the teacher not knowing what the student’s response may be. He or she almost always already studied the potential answers and inventions and anticipated them.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.