Ten Commandments Aren’t Gun Control

- Share via

Instead of enacting a Senate-approved bill requiring a three-day background check for gun show purchases, the House has voted to permit states to allow the posting of the Ten Commandments in schools, courtrooms and other government buildings. The Ten Commandments Defense Act Amendment was approved Thursday by a vote of 248 to 180.

These 248 congressmen violated their oaths to support the Constitution by voting for a bill that clearly violates the 1st Amendment.

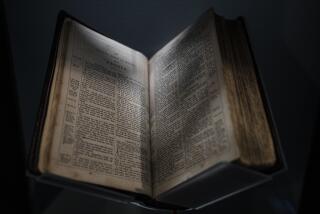

Let us recall what the Ten Commandments actually say. Most Americans believe that they are limited to the famous “thou shalt nots”--kill, commit adultery, steal, bear false witness and covet. But they also include theological statements and religious requirements.

According to the Jewish version, the First Commandment is “I am the Lord thy God.” Then, before we get to the “thou shalt nots,” there are other specific rules such as, “Thou shalt have no other Gods before me,” “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image,” “Thou shalt not bow down thyself to them nor serve them,” “Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain” and “Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy.”

No wonder the Supreme Court held in 1980: “The preeminent purpose for posting the Ten Commandments on schoolroom walls is plainly religious in nature. The Ten Commandments are undeniably a sacred text in the Jewish and Christian faiths, and no legislative recitation of a supposed secular purpose can blind us to that fact.

“The commandments do not confine themselves to arguably secular matters, such as honoring one’s parents, killing or murder, adultery, stealing, false witness and covetousness. Rather, the first part of the commandments concerns the religious duties of believers . . . .”

Not only are the Ten Commandments explicitly religious, they favor one kind of religion, monotheism, derived from the Bible and accepted as sacred only by the Abrahamic triumvirate of Judaism, Christianity and Islam over the hundreds of other religions practiced by minorities in our heterogeneous nation.

Moreover, there is considerable theological disagreement even among the Abrahamic religions as to what constitutes the Ten Commandments and how they are to be numbered and divided. Literally read, the Decalogue includes 19 different commands and prohibitions. The Jews begin with “I am the Lord thy God,” whereas Christians regard that verse as merely a preamble and begin with, “Thou shall have no other Gods before me.”

Even within Christianity, there is no consensus. According to the Anchor Bible Dictionary, “Christians do not generally adopt the Jewish division of the Ten Commandments into five positive and five negative commandments. Nonetheless, they differ among themselves in the enumeration of the commandments and their consequent distribution in two tablets. The Roman Catholic, Anglican and Lutheran traditions generally consider that three commandments relate to one’s relationship to God and seven to one’s neighbor, thus treating Exodus 20:4-6 as a single commandment and Deuteronomy 5:21 as two commandments. The Reformed tradition divides the commandments into a group of four and a group of six, separating the First from the Second Commandment and treating Exodus 5:17 . . . as a single precept.”

So let the religious wars begin, as Jews and Christians vie for their particular version of the Ten Commandments to be established as the official, state-sponsored account of what was written on the twin tablets that Moses brought down from Sinai amid thunder and lightning.

This is precisely the kind of religious warfare our founding fathers sought to prevent by including in our Bill of Rights the prohibition against any law respecting an establishment of religion. When the 1st Amendment was enacted, we were a nation of Protestants, with small Catholic and tiny Jewish minorities. There were also many deists--believers in God who rejected formal religion--among our founding fathers. Now we are a far more diverse nation, which includes believers in hundreds of religions.

Authorizing the state to post in its classrooms and courtrooms a sacred symbol of one (or two or three) religions and giving it the power to establish one version of that symbol as the official one, will not solve the problem of violence in our schools. It may indeed contribute to an atmosphere of conflict and division.

How should a teacher respond to a student who seeks to post a different religious symbol, say an Islamic declaration of creed, an atheist statement of disbelief, or a Christian proclamation that Christ died for our sins? Does the majority rule when it comes to matters of faith? These kinds of unanswerable questions require the sensible conclusion that personal and often divisive matters of faith belong in homes and places of worship and not in our schools and courtrooms.

Religious control is not a constitutionally acceptable alternative to gun control.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.