Trial of Former Enron Chiefs Starts Today

- Share via

HOUSTON — It used to bother Ken Horton that his fellow former Enron Corp. employees weren’t as upset as he was about what had happened to them.

“It almost made me angry that they seemed so laid back,” said Horton, 42, a finance whiz who worked in Enron’s risk management operation. Along with about 4,000 co-workers, he lost his job and retirement savings when the company collapsed in a financial scandal.

“It definitely pushed my retirement back a good five or 10 years,” Horton said of his loss of hundreds of thousands of dollars in savings and stock options.

Yet Horton has “moved beyond a lot of the initial anger” and today finds himself wanting something he couldn’t have imagined wanting a few years ago: a fair trial for his former bosses.

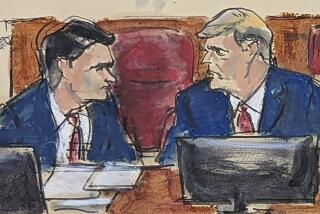

Jury selection begins in federal court here this morning in the fraud and conspiracy trial of former Enron Chairman Kenneth L. Lay and Chief Executive Jeffrey K. Skilling. Four years have passed since Enron’s Dec. 2, 2001, Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing, but now things are moving fast.

U.S. District Judge Sim Lake said he expected a jury to be chosen in less than a day, and he told Assistant U.S. Atty. John C. Hueston -- a federal prosecutor in Orange County before joining the Justice Department’s Enron Task Force -- to be ready to deliver his opening statement first thing Tuesday morning.

The Lay-Skilling trial is the capstone of the recent corporate fraud cases, which followed scandals that darkened such names as WorldCom Inc., Tyco International Ltd., Adelphia Communications Corp. and HealthSouth Corp. and have prompted tough new laws to hem in corporate excess.

The stakes in the downtown Houston courtroom could scarcely be higher. Lay and Skilling could spend the rest of their lives in prison if convicted of all charges. And for many people, this single verdict will determine whether the government’s anti-corruption crackdown has been a success or a failure.

The defendants’ legal teams have argued strenuously -- and unsuccessfully -- that they can’t get a fair hearing in Enron’s hometown.

“Unlike anyplace else in this country, the Houston community feels uniquely betrayed and ashamed by the demise of Enron,” Daniel M. Petrocelli, Skilling’s lead lawyer, said in a court motion this month. He asked to have the trial moved to a city such as Atlanta, Denver or Phoenix, where fewer people were hurt by the downfall of the energy trading giant.

Petrocelli, a partner in Los Angeles firm O’Melveny & Myers, cited some of the responses of the 280 prospective jurors who answered a lengthy pretrial questionnaire sent out by the court.

“They are all guilty as sin -- come on now,” wrote one. Wrote another, “Mr. Skilling is the biggest liar on the face of the earth.”

Lay and Skilling are accused of lying to Enron employees and the public as part of a conspiracy to hide the truth about Enron’s shaky financial position. Their goal, according to the government, was to prop up the company’s stock price and continue profiting on their own vast shareholdings.

Petrocelli and Michael W. Ramsey, Lay’s chief lawyer, will argue that there was “a very small pocket of fraud” at Enron, mainly confined to former Chief Financial Officer Andrew S. Fastow, former Treasurer Ben F. Glisan Jr. and former Fastow aide Michael J. Kopper -- all of whom have pleaded guilty to felonies and pledged to cooperate with the government. Fastow and Glisan are expected to be prominent prosecution witnesses in a trial that is expected to last four months.

Fastow and his accomplices weren’t interested in fooling the public or boosting the stock price, Petrocelli said Friday. Their only aim was to steal from the company, he said, but when their dealings were exposed, it started a panic reaction in the markets that ultimately toppled an otherwise healthy Enron.

That’s the defense’s case, but Petrocelli said it was hard to persuade people whose minds have already been made up.

He also was frustrated that Judge Lake wanted to complete jury selection in a single day. Petrocelli noted that in the civil case against O.J. Simpson -- a wrongful-death suit in which the family of murder victim Ron Goldman won a $33.5-million judgment -- jury selection took a month.

Skilling said Friday that his fate hinged on seating an unbiased jury.

“If we get a jury willing to listen to the facts, then yes, I’m very confident we’re going to be vindicated,” he said during an interview in O’Melveny & Myers’ temporary offices overlooking the squat federal court building where the Enron Task Force was toiling.

Judge Lake hasn’t bought the defense’s claim that an impartial jury cannot be seated in his court. He excused from the panel scores of potential jurors whose answers to the questionnaire showed bias. That, plus exclusions for hardship, winnowed the pool to about 165 people, of whom 125 have been ordered to show up in court this morning.

Lake said there should be ample time today to probe the remaining candidates for evidence of bias or other disqualifying factors.

The responses of Ken Horton and several other former Enron employees interviewed over the last week seemed to support Lake’s view.

Tracy Michel, 39, a former information technology worker, said she found Lay “friendly and approachable” when she bumped into him in the lobby or an elevator at Enron’s high-rise headquarters.

By contrast, “you didn’t get the warm and fuzzies” from Skilling, she said, adding that she was suspicious of the former CEO because it was he who had hired Fastow.

“If there’s evidence that he did something,” Michel said, she would like to see Skilling punished. At the same time, she felt positive about her Enron experience despite losing her job and several thousand dollars’ worth of stock options and severance pay.

Rob Collier worked for Enron Energy Services, which helped large organizations manage their electricity use. The division, like a start-up company, required constant infusions of cash, but it was never profitable as far as Collier could tell. Even the individual contracts he saw all seemed to lose money. Managers weren’t overly worried about such details, he said, because they believed they were building a business that would be a profit monster just a short way down the road.

“At Enron, everything was the big picture,” said Collier, 46. “It wasn’t like a cautious [research-and-development] approach. You had to go in head over heels.”

Collier, a veteran of the gas pipeline industry, had been laid off before, so he trusted his instincts. He didn’t hold Enron stock in his retirement account. His losses were confined to stock options that became worthless when the company went bust. In what turned out to be another bad break, however, he jumped from Enron to a job in Houston with San Jose-based Calpine Corp., which filed for bankruptcy protection in December.

“Do I want them to get jail time?” Collier said of Skilling and Lay. “I don’t know. I’m not bitter. Hopefully the truth can be finally known.”

The year after Enron’s bankruptcy filing was a grim one for Houston, said Minnette Boesel, a downtown real estate broker active in historic preservation. The city’s self-image took a blow, and the pain of the layoffs and lost savings was still fresh.

“It’s so unfortunate, sort of a bittersweet thing. All the charities that depended on Enron and Ken Lay had a hard time for a while,” she said, noting that Lay had been one of the city’s most energetic fundraisers. But other donors have stepped up, she said, and with the passing of time, the trauma of Enron’s collapse has faded.

Horton, the finance expert, now works for a consulting firm that advises companies on how to comply with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, the reform law adopted in the wake of the Enron scandal.

“The Houston mentality is a little bit special,” Horton said. “You hit a gusher one day, you go bankrupt the next and you start a new company the day after. It’s not too surprising we’ve moved on.”

Skilling said that although the news media have “demonized Enron and demonized Ken and me,” he isn’t treated like a pariah in Houston, where he still lives.

“If I walk into a restaurant and have a conversation and somebody finds out that I was the president of Enron, they’re usually surprised that I’m not like they thought I’d be,” Skilling said.

“People expect me to have a pitchfork and a spiked tail.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.