Column: A claim that a cure for cancer is a year away shows the limits of scientific flapdoodle

- Share via

Desperate people suffering from intractable diseases are the easiest marks in the world for unscrupulous promoters. That’s why scarcely a week passes without someone claiming to have found a cure for some terrible malady or other — and some credulous journalists parroting the claim as the real thing.

This week it’s an Israeli company called Accelerated Evolution Biotechnologies, and the Jerusalem Post. On Monday, the newspaper published an article quoting the company’s chairman, Dan Aridor, as saying: “We believe we will offer in a year’s time a complete cure for cancer. … Our cancer cure will be effective from day one, will last a duration of a few weeks and will have no or minimal side effects at a much lower cost than most other treatments on the market.”

The Post, to give it a teeny bit of credit, remarked, “It sounds fantastical.” But the truth is that the claim is so fantastical that it should never have made it into print, let alone on a news outlet’s “Health & Science” page.

The ‘cure for all cancers’ is an inherently implausible claim. ... Cancer is not one disease, but a category including many related diseases.

— Steven Novella, Yale medical school

Aridor’s bold assertion provoked furious reactions by real cancer scientists that have appeared in print and online in such profusion that they can’t be missed by anyone, no matter how innocent, looking into the assertion.

But it also has generated counter-counterclaims online by conspiracy mongers on the theme of: “See, cancer can be cured but the medical establishment and drug companies will never let this one see the light of day.”

The whole affair is another test of the adage that a lie can get halfway around the world before the truth can get its boots on. To put it another way, once you let an extreme claim like this out in the open, it can be difficult to get it back in its cage.

We’ve seen that in the exploitation of the magic of the term “stem cell” to relieve desperate patients of thousands of dollars at a time for treatments with no known scientific validity.

Bold, ambitious claims that cures for serious diseases lurk just around the corner aren’t only the province of charlatans. Political leaders often fall prey to the same impulse — witness President Nixon’s War on Cancer and President Obama’s Cancer Moonshot, both predicated on the notion that a serious funding surge would, in Nixon’s words, conquer “this dread disease.” California’s own $6-billion stem cell program was sold to voters in 2004 with the promise of cures, for spinal cord injuries, Parkinson’s, diabetes, and much more, that haven’t emerged with the sureness or speed that Californians were led to expect.

It’s true that the money made available through these programs has funded important, legitimate research; indeed, cancers once thought incurable have yielded to treatments that have extended patients’ lives by years or decades. But these programs all were based on a misconception of how quickly science can progress and the nature of the disease targets themselves.

That may be especially true in cancer’s case. “The ‘cure for all cancers’ is an inherently implausible claim,” observes the veteran quack-hunter Steven Novella of Yale medical school, responding to the AEBi claim. “Cancer is not one disease, but a category including many related diseases. Different cancers involve different tissues, different mutations, and different behaviors and features. While some treatments are effective against a variety of cancers, there is no one treatment effective against all cancers (let alone a cure for all cancers).”

With that in mind, let’s take a closer look at Aridor’s statement. To begin with, he’s not a scientist, but an investment marketer. He has a degree in economics and business management from Israel’s Bar-Ilan University and some time spent in an MBA program at Columbia. (It’s unclear if he ever got a degree from Columbia; his CV states only that he was an “MBA student” there.)

AEBi does bring some science to the table in the person of its founder and CEO, Ilan Morad, who claims to have scientific training from Tel Aviv University and Harvard.

Morad has been a bit more circumspect than Aridor about his work, but not by much. “We are working on a complete cure for cancer,” he told The Times of Israel this week. “We still have a long way to go, but in the end we believe we will have a cure for all kinds of cancer patients and with very few side effects.”

But its credibility doesn’t go much further. Aridor’s statements bootstrap some established scientific facts to an extreme promise. According to the Jerusalem Post, “the company’s achievements involve the use of ‘several cancer-targeting peptides’ targeting every cancer cell at the same time, combined with a strong peptide toxin that would kill cancer cells specifically.”

The newspaper, presumably taking its lead from Aridor, points out that the ostensible cure is based on a lab technique that won the Nobel Prize last year. The peptide theory, by the way, isn’t new but has been under study in the field for nearly 20 years.

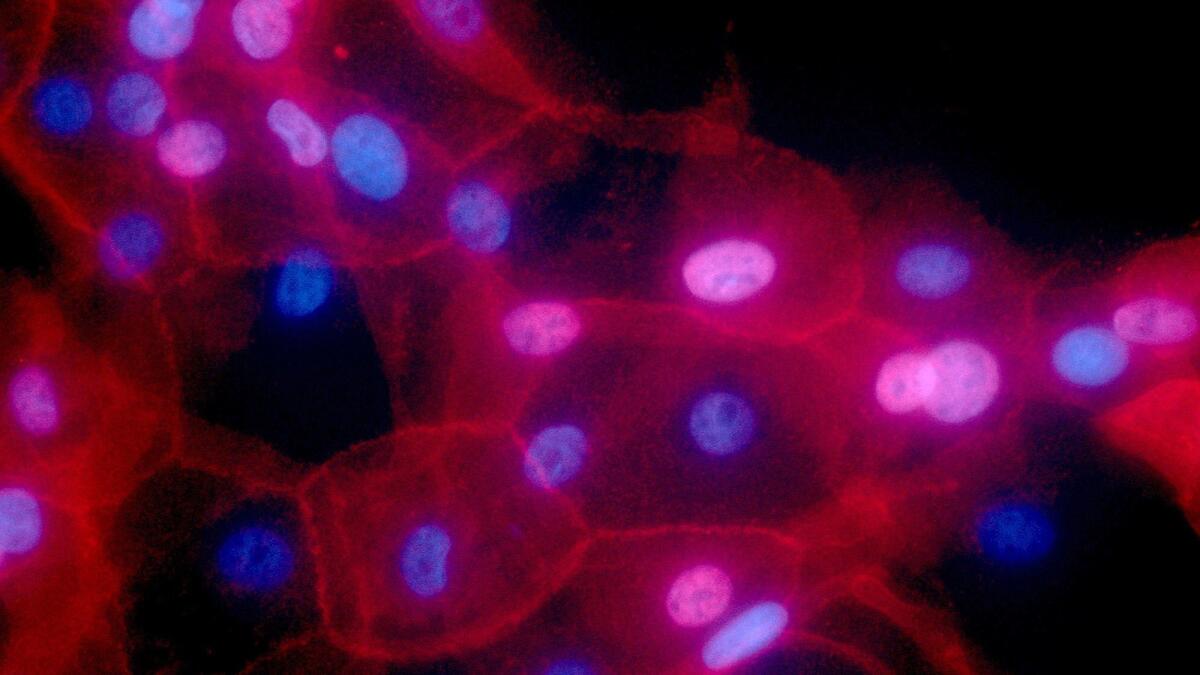

The company acknowledges that it has not tried its treatment on humans, only mice and human cells in the lab. Morad said it hadn’t published any results in medical journals because it “can’t afford” to do so, but said the results it had had were “very good.” The results posted on its website, one cancer expert says, are “underwhelming at best. … They’re selling unicorns.”

Even taking Morad and Aridor at their own level of self-esteem, it’s obvious that their approach would require years of further study, including through rigorous human clinical trials, before being judged ready for patients.

So any claim that would require not just one step, but multiple steps, happening largely in secret in one lab over a relatively short period of time stretches credulity.

Without them, asks Novella, “How does Aridor know that his alleged treatment will have the features he boasts? … In other words — he is just largely making up all those claims. He may suspect that his treatment will be as effective as he says, but he really has no idea.”

The only remotely encouraging aspects of the publicity surrounding the AEBi claim is how quickly it was debunked by legitimate scientists, and the rapid education that credulous journalists and readers received in the realities of trying to cure cancer. There’s hope that the public may someday learn that the more extreme the claim, the greater the doubt it deserves.

“Beware Holy Grail perfect products that just seem too good to be true,” Novella writes. “You will never go wrong being skeptical of hyped claims.”

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email [email protected].

Return to Michael Hiltzik’s blog.