In Fresno, Sikhs and Oaxacans unite to pass caste discrimination ban

- Share via

As a teenager picking apples in the Central Valley town of Mendota, Miguel Arias was puzzled when Mexican farmers yelled the insult “Oaxaquita” at Oaxacans working in the fields.

His parents explained that in Mexico, the system of casta persisted, with some people looking down on those with darker skin or Indigenous heritage.

“As a Mexican immigrant, I just thought we were all Mexicans, and we were all immigrants,” said Arias, a Fresno City Council member who immigrated from Michoacán when he was 2 years old. “Discrimination that Indigenous people in Mexico got … for lack of a better description, it was the dirty secret among our Mexican immigrant community.”

On Thursday, Arias and his council colleagues voted to make Fresno the first city in California to ban discrimination based on caste or Indigenous heritage, while a similar bill sits on Gov. Gavin Newsom’s desk.

The state bill, which passed the Legislature in early September, was intended to protect supposedly lower-caste people of South Asian descent as well as Indigenous people like Oaxacans. It has sparked intense support, as well as opposition from those who say it singles out Hindu Americans as potential perpetrators of discrimination.

In Fresno, the push for the ban was led at first by Sikh residents, whose religion rejects the idea of castes, and the Ravidassia community, who are followers of a 14th century Indian guru who preached caste equality. People of Oaxacan descent soon joined them, as discrimination against those with ties to the southern Mexican state gained widespread attention with the leak of a recording that captured three Los Angeles City Council members and a labor leader in a racist conversation.

‘I thought we had made great progress in the last three years in gaining recognition,’ said one Oaxacan, who criticized remarks by Nury Martinez.

“These proposals in Fresno are trying to say we have an opportunity to address ... this historical legacy of discrimination against untouchables and against Indigenous people,” said Gaspar Rivera-Salgado, a Oaxacan American who is director of the Center for Mexican Studies at UCLA, as well as a board member at the Binational Center for the Development of Oaxacan Indigenous Communities, which was among the groups advocating for the Fresno ordinance.

When Spain colonized Mexico, it established the Sistema de Castas, according to Rivera-Salgado. Those born in Spain as “pure Spaniards” were at the top, followed by Spaniards born in Mexico. Indigenous groups were near the bottom, along with Black people.

“During the colonial period, the Spaniards implemented this system that resembled very much the system of India,” where Brahmins are at the top and Dalits, or untouchables, are at the bottom, Rivera-Salgado said.

In the leaked recording, then-L.A. City Council President Nury Martinez described Oaxacans as “little short dark people” and “tan feos” — so ugly. Then-L.A. County Federation of Labor President Ron Herrera referred to them as “Indios,” or “Indians.”

“They were speaking disparagingly about Oaxacans. Why?” State Sen. Aisha Wahab (D-Hayward), author of the state caste discrimination bill, said of Martinez and Herrera. “Because caste systems exist all over the world, and they may have a different look or a vibe to it, but the discrimination happens, and I think Oaxacans can appreciate that this bill would also protect them in some regard as well.”

Luis López Resendiz, program director for the Indigenous interpreter program at the L.A. Indigenous organization CIELO, said his dad insisted that he “dominate” Spanish as a way to hide his Indigenous identity. His father had often been called Indio or Oaxaquita.

“People hated me when I was speaking my own language in the streets,” López Resendiz recalled his dad telling him. “People tried to shame me because of who I am. I don’t want that for you.”

But schoolmates still made fun of López Resendiz, guessing that he was Oaxacan from the design of his huaraches, he said. Only in college did he begin to speak openly about his background.

As a Mexican American, I love being from two worlds. I’ve thought more about my roots and what it means to be Oaxacan. Then came the L.A. City Council audio leak.

Advocates for the Oaxacan community have long pushed back against the discrimination. In 2012, the Oxnard school district prohibited the words “Oaxaquita” and “Indito,” or little Indian, from being used on school property.

Arcenio López, executive director of Mixteco/Indigena Community Organizing Project, which pushed for the resolution in Oxnard, recalled hearing the epithet Oaxaquita when he came to California from Oaxaca in 2003 and worked in the strawberry fields.

“Many of those youths were facing similar experiences I faced as a farmworker, but in the classroom,” he said. “They felt they didn’t belong to the school system, because other classmates were making fun of them.”

Tens of thousands of Sikhs and Oaxacans, many of them farmers or farmworkers, live in Fresno County and the Central Valley. The two communities have worked together for years.

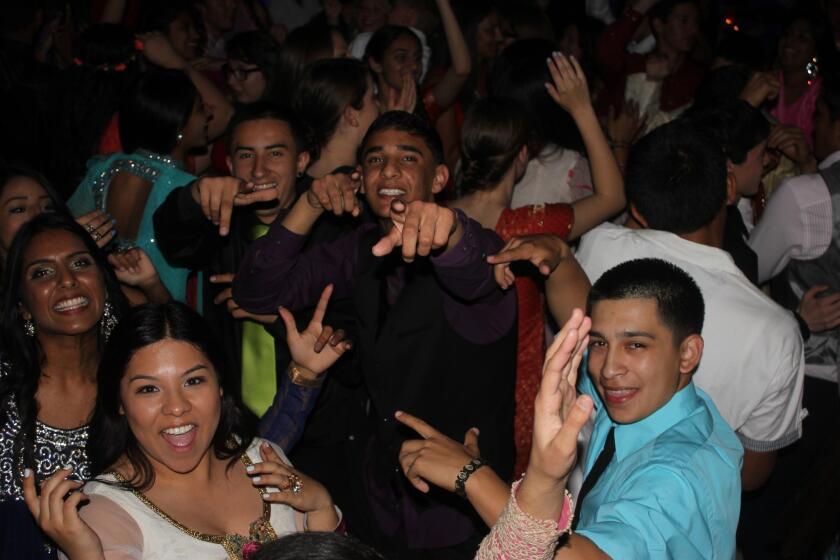

It’s not always easy being a turban-wearing Sikh in Central California. But at Fowler High School, Punjabi students came together to create a special night.

The racist audio leak in L.A. and the passage of a caste discrimination ban in Seattle inspired the two groups to push for the Fresno ordinance.

“When groups have shared a common experience of inequity and being treated as less than, right away they can understand each other’s pain,” said Deep Singh, executive director of the Jakara Movement.

But the state caste discrimination bill, SB 403, has provoked outrage from some Hindu residents.

Satish Vale, a national convenor with Americans4Hindus and an IT consultant in Santa Clara, said existing laws already protect against discrimination based on caste. The bill imposes the idea of caste, when Indian Americans are trying to move away from it, he said.

“When we came from India, we don’t have the caste anywhere represented in our identity cards or in our passports or in our degrees,” Vale said. “Caste is like an N-word for us.”

In Fresno, there was little opposition to the city caste discrimination measure, which passed 6 to 0.

At a news conference Thursday after the City Council vote, leaders of the Jakara Movement and the Binational Center for the Development of Oaxacan Indigenous Communities called for Newsom to sign SB 403.

Thenmozhi Soundararajan, who has been on a hunger strike for nearly a month as she awaits Newsom’s decision, was among the advocates for the bill who joined the news conference.

“When we think about things like the casta system, things that led to genocide, things that led to the othering of Indigenous people, we see ourselves in their struggle as caste-oppressed people,” Soundararajan said, “because we, too, have been oppressed for centuries.”

Times staff writer Suhauna Hussain contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.