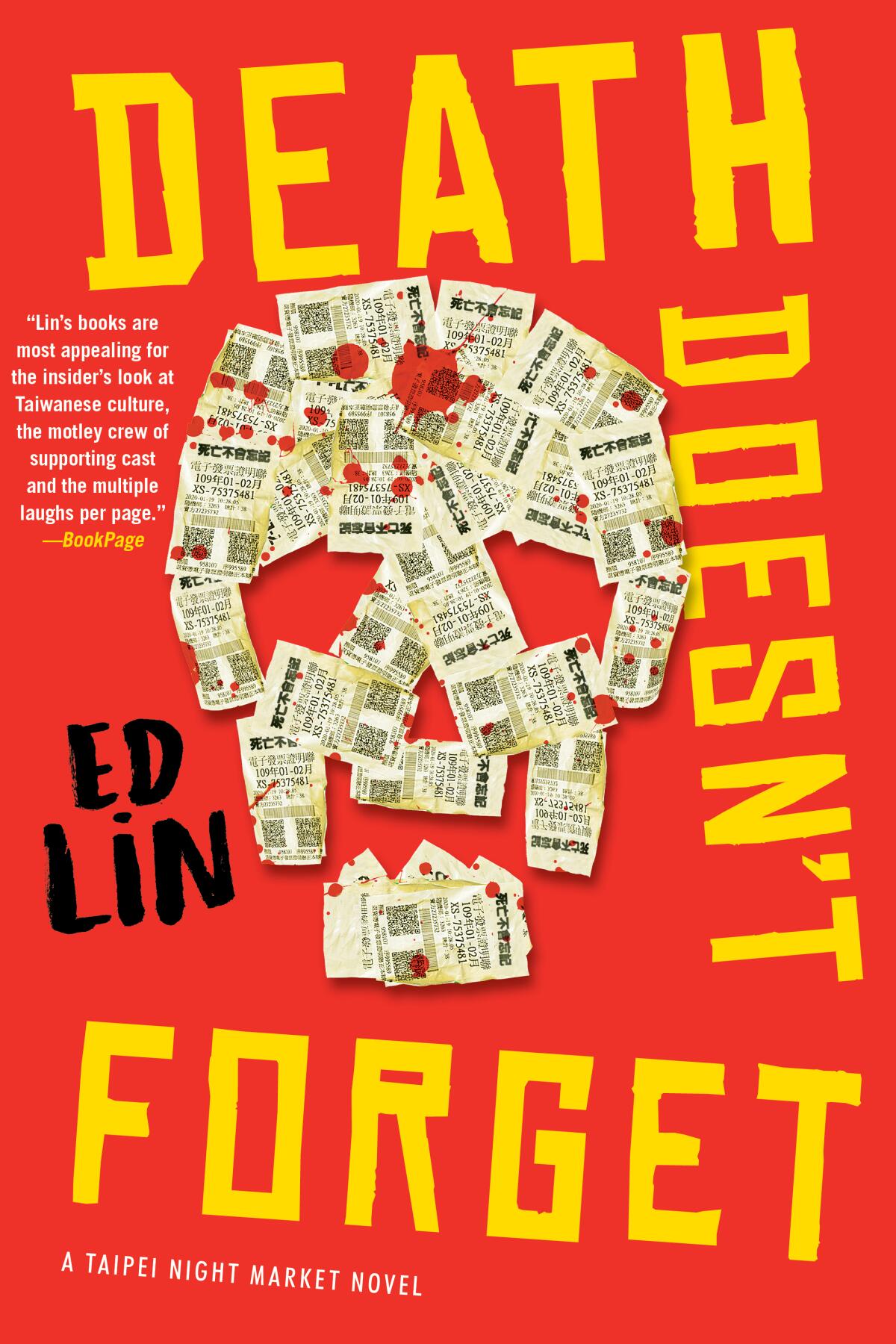

Review: A master of Taipei noir proves every good crime novel is a social novel

- Share via

The crime novel is, by its nature, a social novel. Among its most necessary characters is setting, which functions not as backdrop but milieu. “The detective story, so peculiar to the modern city, can involve an extraordinary range of humanity, from the very rich to the very poor,” Frank MacShane noted in his 1976 biography “The Life of Raymond Chandler.” What was true in MacShane’s (or Chandler’s) time remains so now.

As Ed Lin writes in the opening pages of “Death Doesn’t Forget,” his fourth Taipei Night Market novel, “Every paper receipt in Taiwan is a lottery ticket for cash prizes from the government. It’s the Ministry of Finance’s way of ensuring that people ask for receipts for their purchases. When the QR codes are scanned for lottery winnings, they create electronic trails of taxable income that can be checked against businesses that try to cheat.”

That’s a necessary bit of information because “Death Doesn’t Forget” begins with a low-level hood named Boxer winning 200,000 New Taiwan dollars — the equivalent of about $6,700 American. But it’s also a reminder that Lin’s novel takes place in a landscape where everyone wants a piece of the action and nothing is quite what it seems. Boxer represents a case in point: If not a MacGuffin, exactly, he is something of a red herring, a dead end. Although the book starts with him, he is soon dead in a derelict apartment, “head split nearly in half.”

If there’s something oblique about Boxer as a point of entry — as in Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho,” it lets us sidle into the main narrative — it’s also fitting because it mirrors the offhand way Lin introduces his true protagonist, Chen Jing-nan. At 25, with “the longish face of an anime hero, but fatter, because he was human,” Jing-nan runs the food stand Unknown Pleasures at a Taipei night market; he was the last person to see Boxer alive. When a cop is also killed, he becomes a suspect in both deaths.

L.A.’s authors, from 19th century novelists to Wanda Coleman to Steph Cha, have always pushed genre boundaries and dissected California myths.

This too is a MacGuffin, as the detectives working the case admit the evidence does not add up. “We know you probably had nothing to do with the murder,” one tells Jing-nan. “But there is the fact that his appointment with you was his last order of business for the day. We wanted to know if you could tell us anything that might help the investigation.”

The effect is like a fun house mirror, in which even the facts can seem distorted, and neither Jing-nan nor the other principals — his girlfriend, Nancy; her bar-hostess mother, Siu-lien, who lived with Boxer; and his employees, Dwayne and Frankie — can be certain where they stand. “Nothing made sense,” Jing-nan reflects in the middle of the novel. “The past two days were like a crime film with no imagination, budget, or second takes.” Such uncertainty — or unpredictability — extends to the characters themselves. Nancy, for instance, is a graduate student, estranged from her mother until Boxer’s death gives them an opportunity to reconnect. Frankie is a former political prisoner who supports Indigenous peoples’ rights. Together, their backstories weave a tapestry that also frames the cultural and political landscape: the crime novel as social novel again.

All of this comes into focus after Jing-nan and Nancy decide to volunteer at “an assisted-living facility … serving aboriginal people” — which not only helps them resolve the mystery but also highlights the divisions that define contemporary Taipei.

Lin is nuanced with these details. Taiwanese American, he was raised in New York and wrote a series of crime novels set in that city’s Chinatown before publishing the first Taipei Night Market book, “Ghost Month,” in 2014. Working from his food stall, Jing-nan offers an inspired take on the outsider detective, recalling Walter Mosley’s Easy Rawlins or Naomi Hirahara’s gardener-investigator Mas Arai. What is the market, after all, if not a crossroads?

Naomi Hirahara’s “Clark and Division,” set in Chicago, shines a light on the little-known aftermath of internment. It’s a crime novel only she could have written.

Lin makes this explicit in the scenes at Unknown Pleasures, which reveal the complexity of its proprietor’s world. “Jing-nan turned his attention to what the stall would be offering tonight,” Lin writes in one such moment. “As he did most nights, Jing-nan pondered the ultimate questions: What would tourists visiting Taiwan believe was authentic, and what price point would they be willing to pay for a bite of this authenticity?”

Here we see the character in perhaps his most essential incarnation: as an entrepreneur intent on a successful business, for whom the resolution of the killings is, if not incidental, then one among a series of overlapping concerns.

For Lin, this is the whole idea: to set the murders within a larger frame. It’s not that he ignores the investigation, just that the most compelling dramas remain (intentionally) the most personal and human: Siu-lien’s complicated reckoning over Boxer; Dwayne and Frankie’s efforts to discover themselves. Most vivid is the relationship between Jing-nan and Nancy, which ebbs and flows in the way of real love. “They didn’t tell each other little things, anymore,” Lin writes. “Maybe they would begin to talk less about everything. They could end up as one of those older couples that dined in silence. … Maybe they were at the point where something terrible happens — such as the death of Siu-lien’s boyfriend — that makes them put everything on pause, and meaningfully reconnect.”

This sort of conditionality motivates a lot of crime fiction, although mostly on existential terms. What differentiates “Death Doesn’t Forget” is its sense not of despair but of equanimity. The future is unwritten, in other words; it must be lived to be revealed. Even as the novel reaches its conclusion, Lin leaves open a number of questions about what will happen, what the characters will choose. In part, this is a convention of the series, since everyone must live to animate another book. But that’s too reductive for what Lin has done here, which is to write a crime novel as a slice of life. “It’s like any other job,” Frankie tells his wife when she wonders what it’s like to operate at the edges of the law. “It’s mostly mundane, but once in a while, it’s someone’s birthday and you get a slice of cake.”

Part of the joy of reading is the way it can disturb us.

Ulin is a former book editor and book critic of The Times.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.