Giving credit where it’s due — but not on TV

- Share via

Welcome to the Wide Shot, a newsletter about the business of entertainment. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

Times film business reporter and Wide Shot founder Ryan Faughnder is on paternity leave; veteran media reporter Meg James is filling in.

This week, the Wide Shot tackles a topic that has prompted showrunner pushback, a Change.org petition and lingering resentments in living rooms across Los Angeles — and beyond.

You’ve probably noticed that closing credits of movies and TV shows have been shrinking, speeding up and, in some cases, disappearing entirely. A TV show or movie ends, and just as the credit sequence starts to roll, Netflix or another streamer cuts to the next episode of the program. Linear TV networks have also squeezed film credits to a small box, dedicating much of the on-screen real estate for a promo for another episode or a commercial for insurance or some other product. It can be maddening when credits, downgraded to a corner of the screen, fly by at lightning speed.

“It’s just insulting. These channels are denigrating the credits by making them so small that you can’t read them,” fumed Jason Squire, a film expert and author of “The Movie Business Book.” He likes to watch old episodes of “Law & Order” on the Sundance TV channel and feels that the AMC Networks channels, among others, have trampled on his joy.

The practice is a blow to a Hollywood filmmaking tradition: inviting viewers to pause for a few minutes when a program ends to pay homage to the hundreds of workers — particularly below-the-line crews — who toiled to make the movie.

This is not a new phenomenon, but it is one that tugs at an age-old debate: Is a film more art than commerce? Or the other way around?

Dissing the credits underscores the difficult balancing act for TV networks and streamers. Sure, programmers support bringing a filmmaker’s creative vision to the screen as long as it doesn’t interfere with their ability to make money and hold onto viewers during a challenging time for the industry.

Four years ago, story editor Mark Boszko launched a Change.org petition with the headline, “Netflix, We Want to Watch the Credits.” More than 13,500 people signed his petition.

“I do like to watch the credits, then listen to the music and kind of be in the space of the movie,” said Boszko, who now lives in Los Angeles. “It just gives me a minute to think about what I just watched. I feel like it’s a little disrespectful to just shrink the credits down into this tiny box. And it’s not just Netflix; the other streaming services are doing this now.”

Netflix does offer a “watch credits” button, but it vanishes in seconds — often before you can fumble with the remote. Hulu and other streaming services offer the ability to change a user’s default settings so that film fans can watch the credits.

That’s not possible on linear television.

“Our networks are employing ‘the squeeze,’ because the credits have become so much longer now, particularly for movies,” said one television executive who did not want to be identified speaking ill of the closing credits.

Representatives of Netflix and AMC Networks declined to comment.

But programmers say viewers have short attention spans. They worry that audiences will flee if they are asked to watch several minutes of credits before another episode begins. Networks, which have witnessed a dramatic migration of viewers, are challenged to keep audiences tuned in.

The Wide Shot asked Raphael Bob-Waksberg, who is running for the board of the Writers Guild of America, West, whether restoring credits to prominence was a plank of his campaign. Not exactly, said the creator of “BoJack Horseman”; who is also an executive producer on “Undone,” for Amazon Prime and “Tuca & Bertie” for Netflix.

But he has strong feelings on the topic and has fought for the credits when negotiating deal points.

“My request that I try to work into my contracts is that networks and streamers will not distort, shrink, cover up or automatically skip the credits,” Bob-Waksberg said. “But whenever I make that request, the people I’m negotiating with say, ‘No, we will not guarantee that.’ ”

So he pushes the issue further.

“Sometimes I’ll ask for a penalty of some sort,” he said. “If you can’t promise me that you’ll run the credits, then I want you to pay some of amount of money to all of the people whose names that you’re skipping. The deal that [crew members] agreed to is to work partially for pay and partially for credit. And if you are not offering them that credit, then I think you are not fulfilling your end of the bargain.”

The problem, Bob-Waksberg said, is that the WGA contract doesn’t require credits to be visible, so individual creatives lack leverage.

“Clearly, they have numbers, they’ve done research and there’s a reason that all these streamers and networks do this,” Bob-Waksberg said. “But I feel it’s disrespectful to the people who make the shows. It sends the message that we don’t actually care about these people.”

Makers place great pride in every element of an episode, often including closing sequences. Occasionally, there’s a message to viewers, a sly wink from the makers after an episode’s final scene. Good luck trying to read showrunner Chuck Lorre’s famous vanity cards at the end of a cable repeat episode of “The Big Bang Theory” or “Young Sheldon.” It looks more like chicken scratches.

“I find that when I’m watching something, the streamer immediately shuffles me off to the next episode or to some ad for a product, then I forget that feeling that I just had,” Bob-Waksberg said. “It cheapens the art.”

Stuff we wrote

— Anousha Sakoui reported that two of Hollywood’s biggest unions are blaming the major studios for failing to enact legislation that would regulate guns on film sets after the October shooting on the “Rust” movie set. The story followed her piece from last week about how the latest effort in Sacramento to regulate the use of firearms on movie and TV sets in California had failed to gain support from both Hollywood unions and the film industry. Last-ditch efforts failed to produce common ground.

— Stephen Battaglio explains why Warner Bros. Discovery has taken aim at children’s programming on HBO Max, including episodes of the family favorite “Sesame Street.” When trying to cut $3 billion in annual costs, you have to start someplace.

— The Producers Guild of America elected its first woman of color, Stephanie Allain, to serve as president of the organization that represents Hollywood producers, Sakoui wrote. Allain, a former executive at 20th Century Fox and Columbia Pictures, was elected president alongside former Paramount Pictures President Donald De Line to lead the guild, whose history dates back to 1950.

— Sports writer J. Brady McCollough travels to Tennessee to profile ESPN broadcaster Kirk Herbstreit, who is excited for the return of college football and joining the announcing team, along with legend Al Michaels, for Amazon Prime Video’s “Thursday Night Football.” Herbstreit suffered a major health scare last spring when a cluster of blood clots passed through his heart and settled in his lungs.

— Rick Carter is an Oscar-winning film production designer and instrumental in creating fantastic worlds depicted in “Avatar,” “Back to the Future,” “Star Wars: The Force Awakens” and “Forrest Gump.” Carter told me that he was delighted that a retrospective of his work at El Segundo’s art lab, ESMoA, turned into a platform for eight young artists, who along with Carter, created a giant collage that remixes blockbuster movie iconography.

— Longtime baseball writer Mike DiGiovanna took us inside the Los Angeles Angels’ lost years filled with questionable decisions, cost-conscious management and Arte Moreno’s influence. Despite boasting two of the biggest starts in baseball, the Anaheim club is near the bottom.

Number of the week:

This Saturday, tickets will be just $3 in the vast majority of American movie theaters as part of “National Cinema Day,” a new campaign launched by the Cinema Foundation, a nonprofit arm of the National Assn. of Theatre Owners. The national discount day, which will be observed in 3,000 cinemas and on more than 30,000 screens, seeks to stimulate interest during a lull in the movie pipeline that is hurting theater chains.

Catch-up reading...

Last week, the Wall Street Journal’s Joe Flint broke the news that NBC is considering scaling back its primetime hours to two from the traditional three. The Comcast-owned network is considering ceding the 10 p.m. hour to its owned stations, like KNBC-TV Channel 4, or its affiliate station partners so they can run local news or their own programming. The effort would be a way to dramatically cut costs.

The 10 p.m. hour has long been reserved for a network’s prestige programs — scripted dramas — and more provocative fare. The thinking used to be that most kids were in bed by then, so programs could tackle more adult themes.

If NBC shrinks the primetime block to two hours (8 to 10 p.m.), it would mean fewer slots in the schedule for show creators. And if CBS and ABC were to follow suit, that would erase 21 hours a week in prime-time real estate. Fox Broadcasting has always scheduled two hours a night in primetime.

NBC hasn’t officially discussed the matter with its board of affiliate TV stations, Flint wrote. The bulk of the advertising for the upcoming season has already been sold. The earliest such a shift could take place would be fall 2023.

Vox’s Peter Kafka looks at changes at CNN and the long shadow cast by John Malone, a legend in the cable TV business and the godfather of sorts to Warner Bros. Discovery Chief Executive David Zaslav. Kafka writes that people close to the two men insist that Zaslav is remaking CNN for both business and editorial reasons — and not because of pressure from Malone .

The New York Times’ Jeremy Peters writes that Sean Hannity has joined the list of Fox News heavy-hitters who have been or will soon be questioned by lawyers representing Dominion Voting Systems in its $1.6-billion defamation suit against the Rupert Murdoch-controlled network.

Bloomberg’s Lucas Shaw, in his newsletter, writes about cultural cognitive dissonance. Moviegoers seem to think this has been one of the best years for blockbusters this century. Critics think it’s been one of the worst. The two camps agree on the quality of only two of the year’s biggest films, “Top Gun: Maverick” and “The Batman.”

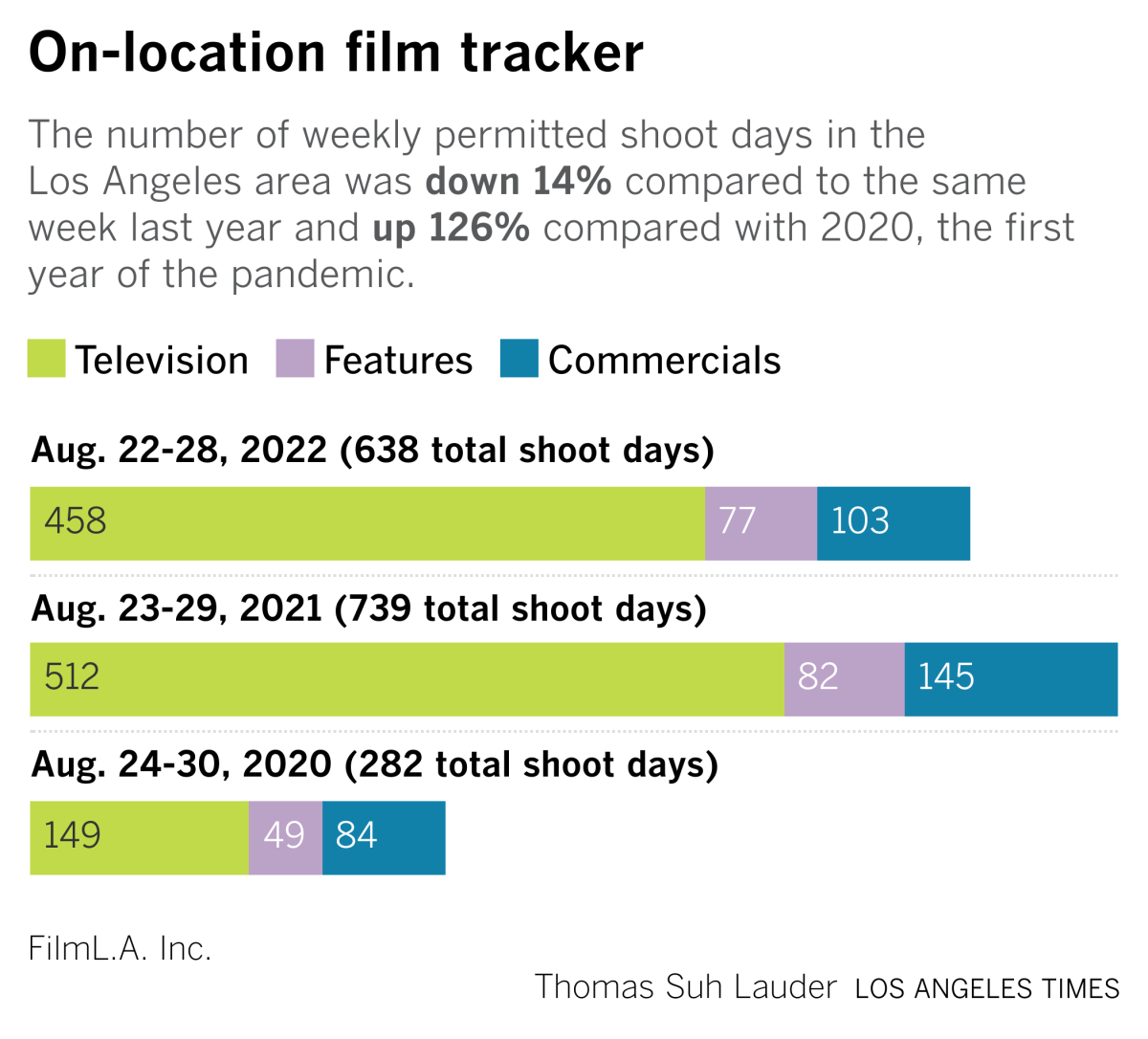

On Location

Finally ...

“Steep, icy and ‘vicious.’” In this case, we’re not talking entertainment corporate politics but rather the treacherous trip up California’s Mt. Shasta. This story, deeply reported and written by enterprise reporter Jack Dolan, took my breath away. Dolan chronicled how a day of climbing turned deadly for an experienced guide. The story was accompanied by magnificent visuals produced by Myung J. Chun, Robert Meeks, Steve Saldivar, Karen Foshay, J.R. Lizarraga, Sydney Burton and Lorena Iñiguez Elebee.

Credit where credit is due.

One more click! Please follow me on Twitter.

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.