Ed Asner had too many credits to print. Here’s why Lou Grant best captured his genius

- Share via

A young woman is applying for a job as a secretary at a Minneapolis local news program. Although the job has been filled, she finds herself in the office of the news director who, wanting a drink and not wanting to drink alone, offers her one as he pulls a bottle of Scotch from a desk drawer. (“All right,” she says, finally, “I’ll have a brandy Alexander.”) Seeming to interview her anyway, he asks what even then would have been considered inappropriate questions, and when she stands up to him, he comes close and says, smiling, “You’ve got spunk.” When she takes that as a compliment, he adds, frowning, “I hate spunk.”

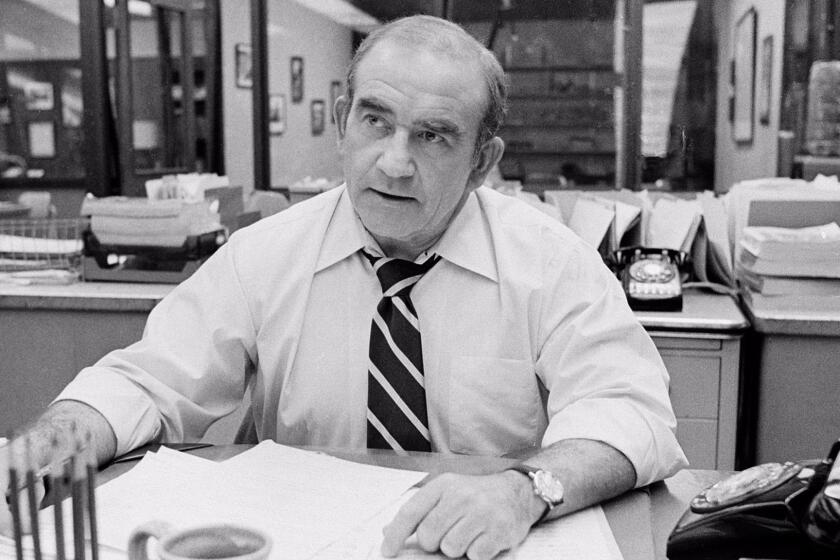

Thus did Ed Asner, who died Sunday at the age of 91, deliver the best-remembered line from “The Mary Tyler Moore Show.” (Shifting back into neutral, he hires her as an associate producer, on a whim.) That series, which ran from 1970 to 1977, would earn him three Emmy Awards — better said, he would earn the series three Emmys, to which the spinoff “Lou Grant,” which aired from 1977 to 1982 and transported the character from a multi-camera sitcom set at a TV station into a single-camera newspaper drama (not without humor), would add two more. Asner would earn another two Emmys while he was still playing Lou, one for the 1976 miniseries “Rich Man, Poor Man,” as an immigrant patriarch, and one for “Roots” the following year, as the morally conflicted captain of a slave ship, as if to remind viewers that he had taken on other sorts of roles before and announcing that he would again.

Ed Asner, the versatile actor who starred on TV in ‘The Mary Tyler Moore Show’ and ‘Lou Grant,’ and movies such ‘Elf’ and ‘Up,’ dies at 91.

Asner was just past 40 when “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” debuted and less than a third of the way through his career. He would work regularly through his 80s and when he died had several projects in pre- and post-production.

In broad terms, his career followed a trajectory not uncommon to the era: theater in college, a little acting in the Army, local stage work. He was a founding member of the Chicago-based Playwrights Theater Club, which would become the Compass Players, which would give birth to Second City. This was followed by a move to New York in the mid-1950s for theater and television work, and then a move west, alongside television production itself, in the early ‘60s.

Through the ‘60s, in the era before “Mary,” Asner worked tirelessly; he would have been familiar to anyone who paid even a little attention to the character actors who make up the bulk of screen roles at a time when television, being highly episodic, brought in sizable guest casts every week. Now and again he would score a recurring role; sometimes he would return to the same show as different characters. “Naked City,” “The Defenders,” “Dr. Kildare,” “The Untouchables,” “Route 66,” “The Outer Limits,” “Gunsmoke,” “The Fugitive,” “Medical Center,” “The Rat Patrol,” “The Wild, Wild West,” “Mission: Impossible,” “The Virginian,” “Run for Your Life” — this is a sliver of Asner’s appearances in those years. You could fill paragraphs just listing them. There were movies too: “Kid Galahad” (Asner’s first feature) with Elvis Presley and “Change of Habit,” again with Presley (and Moore, though they had no scenes together); “They Call Me Mr. Tibbs!” with Sidney Poitier; shot by John Wayne in “El Dorado.” And, again, more.

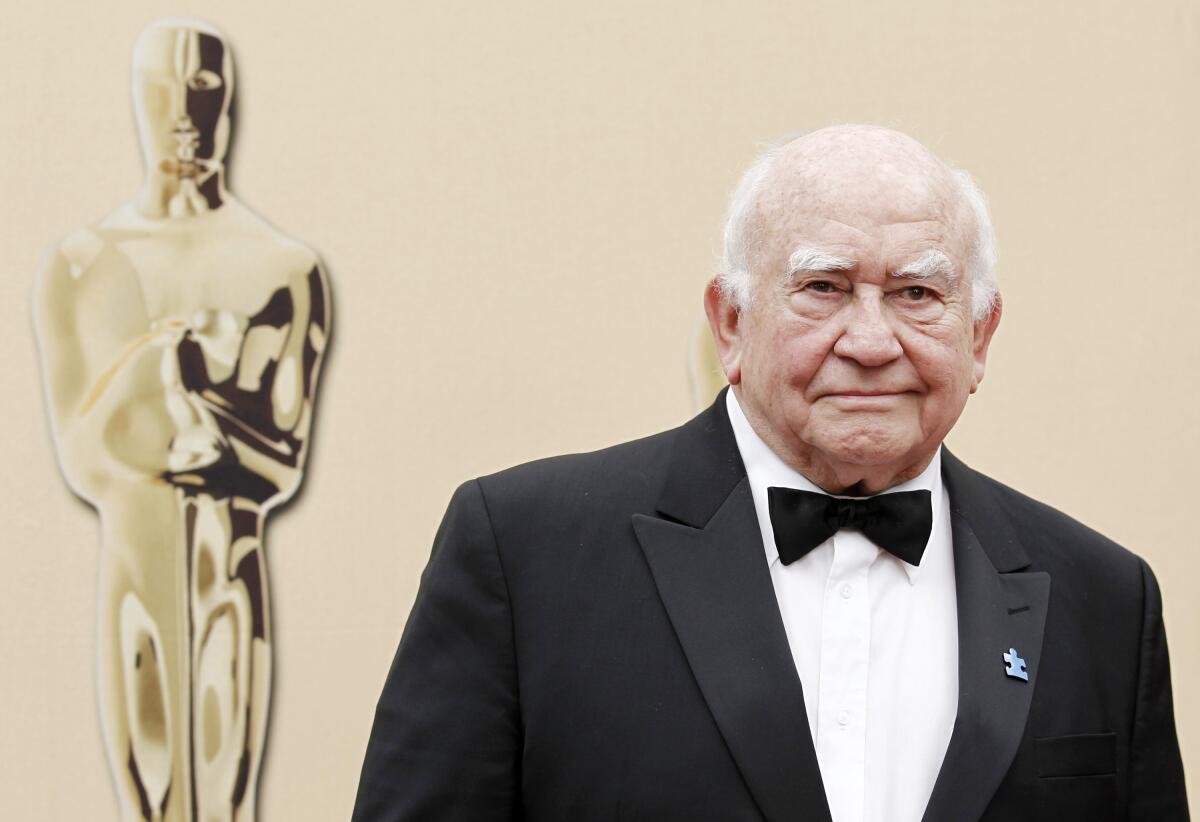

Then there is the period after “Mary,” decades in which every appearance comes accompanied by years of banked goodwill; he is famous, not merely familiar, not just an actor but a friend. His presence feels like a benediction. There were regular parts in several less successful sitcoms, recurring roles in well-established programs, voiceover work (lots of bit parts in superhero cartoons and a starring role in the Oscar-winning “Up”) and documentary narration — usually something related to the left-wing politics whose expression, Asner believed, led to the cancellation of “Lou Grant.” There was stage work as recently as 2019; if a pandemic hadn’t gotten in the way, there might have been more.

On television he continued to show up in interesting and varied places. In the last decade alone, you could find him on “Grace and Frankie,” “The Good Wife,” “Blue Bloods,” “Bones,” “Modern Family,” “Doom Patrol,” “The Boondocks,” “The Glades,” “Dead to Me,” “MacGyver,” “SpongeBob SquarePants,” “Cobra Kai,” “Mom,” “Royal Pains” and, to reunite with Betty White, “Hot in Cleveland.” And, again, more. (I apologize to every Asner appearance not mentioned here. There is only so much room.)

And of course, of course, of course, there was his Santa Claus, a role he played more than once but most notably, and perfectly, opposite Will Ferrell in “Elf.” Really, the best Santa ever.

With a résumé as dense as Asner’s, it’s difficult to develop a unifying theory as to his work, but the key may in any case be in his contradictions. All good actors contain multitudes, but Asner seemed to embody them; even the fact that he was raised as an Orthodox Jew (he rebelled) in Kansas City, Kan., feels somehow appropriate. An everyman who didn’t look like everybody, he was physically formed to be a character actor. Built like a Eugene O’Neill coal stoker, with ears that stuck out and heavy eyebrows above kind eyes, he could read as cuddly or threatening, or even cuddly and threatening, as necessary. But he didn’t play single attitudes; he could make the expected or unexpected choice from moment to moment without ever seeming out of key. If you think of him as “gruff,” an adjective that easily springs to mind, you only have to watch for a minute and you might revise your estimation to “practical,” “boyish” or “shy.” His transitions from one state to another are seamless; they overlap, blend, form chords. His businesslike characters are also dreamers; the weary ones are balanced by wistfulness. His Santa has an edge to cut the sweetness. His comedy calls on a well of hurt.

By virtue of a long life, consistently good writing and a genuinely bonded cast, “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” developed a kind of gravitas over the years, ripened and matured, without dulling the comedy; the end is deep and moving. In the penultimate episode, Mary, whose dating life has been serially unsatisfying, decides perhaps the thing to do is to date Lou. Theirs has been a relationship with almost no sexual tension, yet in most every other sense they are clearly significant others. (“We’re not a man and a woman; we’re friends,” says Lou, when she asks him out. “We care for each other a great deal. How can two people like that date each other?”) After a lot of teenage awkwardness, they finally kiss, seriously, and slowly, mutually collapse into giggles.

Mary Tyler Moore, who died Wednesday at age 80, was the second great woman of television.

The final “Mary Tyler Moore,” in which the station’s new owner fires the staff (except for Ted Knight’s Ted Baxter, the world’s worst news anchor) is still something to behold; watching it again last night, it struck me as maybe the most intimate thing I’d ever seen on television. You’re watching the actual end of something, not merely actors enacting the end of something; the tears are real. Asner is particularly brilliant as Lou keeps warning Mary away from expressing something that will make him break down, only to break that dam himself: “I treasure you people.” When they embrace — eventually it’s a group hug — you want to turn away. (Of that group, only Betty White remains.) Eventually a joke breaks the tension: They move as a unit to grab some tissue, because no one wants to let go.

And so we come to another ending, still not wanting to let go.

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.