Far from Lake Powell, drought punishes another Western dam

- Share via

This is the May 12, 2022, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

Water is flowing through two of three hydropower turbines in a blockish building at the base of Flaming Gorge Dam, so I can feel the floor buzzing — vibrations pulsating through my body — as Billy Elbrock leads me past the blue-and-yellow Westinghouse generators. The warehouse-like space is adorned with an American flag, and with the 1965 logo of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

For the record:

3:16 p.m. May 12, 2022An earlier version of this article misstated the location where the Green and Colorado rivers meet. Their confluence is in Canyonlands National Parks.

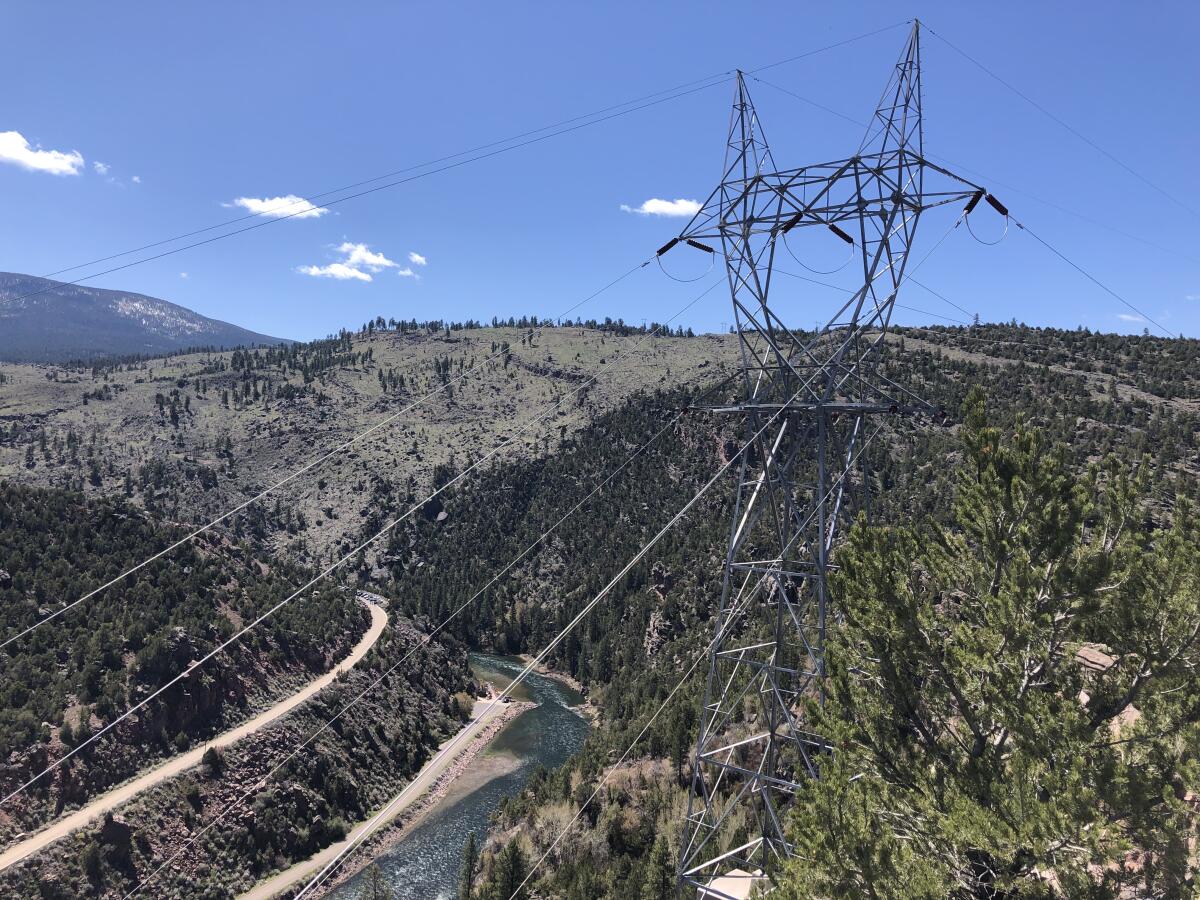

The electricity generated here, in northern Utah near the Wyoming state line, helps keep the lights on across 10 states. It’s made possible by a dam that interrupts the Green River, which flows into the Colorado River in Canyonlands National Park hundreds of miles downstream before meandering southwest to Lake Powell, and then to Lake Mead — meaning as an Angeleno, I’ve been drinking this water my whole life.

Even with everything I know about the ecological damage wreaked by dams, I can’t help but be impressed.

Flaming Gorge is clearly a marvel of engineering, from pendulum-like “plumb lines” that help Reclamation employees ensure the 60-year-old concrete structure isn’t moving around too much, to “weep holes” that reduce pressure buildup by allowing water to seep through fissures in the canyon walls on either side of the dam. Electric lines extend upward from the blockish power plant, soaring out of the canyon through a series of transmission towers that send carbon-free energy to the Black Hills, Burbank and beyond.

I get a small thrill when Elbrock, the dam’s acting manager, tells me I can put my hand on the spinning bit of machinery connecting one of the hydropower turbines below our feet to the electricity generator above. The rotor is spinning four times per second.

“This is the lifeblood of the West — water,” says Jaydee Guymon, a high-voltage electrician with the Bureau of Reclamation, as we stand on a walkway at the foot of the dam, watching the swirling pools of water where the Green River emerges from the turbines. “The earlier settlers knew that. So they started damming up their little [rivers] and streams, because that is the lifeblood.”

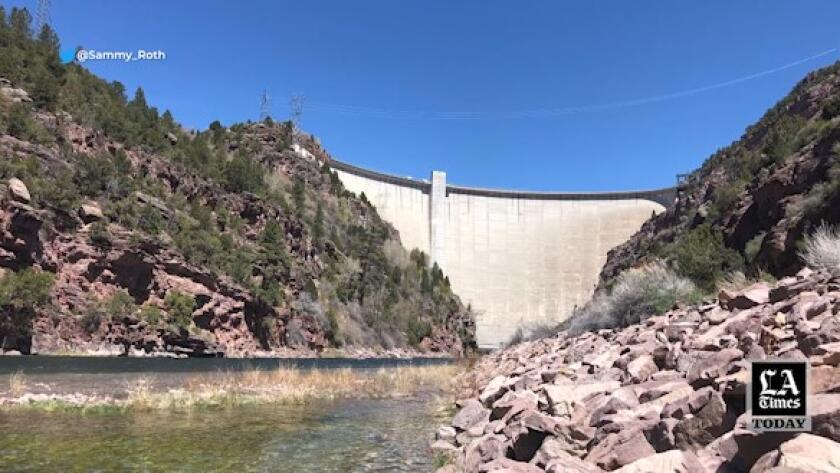

That’s one vision of the West — a civilization made possible by water and power behemoths such as Flaming Gorge Dam, which stretches 502 feet from top to bottom. But it’s a vision that’s challenged by aridification and climate change.

Guymon acknowledges as much when I ask him whether any semblance of normalcy will ever return to this place.

“The trend’s more dry, isn’t it?” he says. “We’re crossing our fingers. We hope that it gets wetter. That keeps us in business.”

Flaming Gorge has been in the news lately because of its increasing role in propping up Lake Powell — the nation’s second-largest reservoir, and a crucial source of drinking water and electricity for tens of millions of people.

The Biden administration said this month it would release an extra 500,000 acre-feet of water from Flaming Gorge Reservoir over the next year, as part of a desperate effort to stop Powell from falling so low that Glen Canyon Dam can no longer generate power. That’s on top of the 125,000 acre-feet that Flaming Gorge contributed to Powell in a first-of-its kind series of releases last year.

Even before 2021, the 65-square-mile Flaming Gorge Reservoir — which is mostly in Wyoming — was feeling the consequences of a two-decade megadrought made worse by fossil fuels. Flaming Gorge’s “bathtub ring” isn’t as stark as the infamous white strips along the edges of Powell and Mead, showing how far water levels have fallen. But it was still one of the first things I noticed when I arrived at the artificial lake last week after driving an hour north from Vernal, Utah, with Times photographer Robert Gauthier.

Rob and I were following the route of a planned 732-mile electric transmission line that will ferry wind power from Wyoming to Southern California. But as a Western energy, water and history nerd, I couldn’t help but schedule a side trip to Flaming Gorge.

I was rewarded by the sight of a plaque indicating the dam had been dedicated by Lady Bird Johnson, wife of President Lyndon B. Johnson. I also got access to places that hardly anyone gets to go, especially since the pandemic put an end to guided tours.

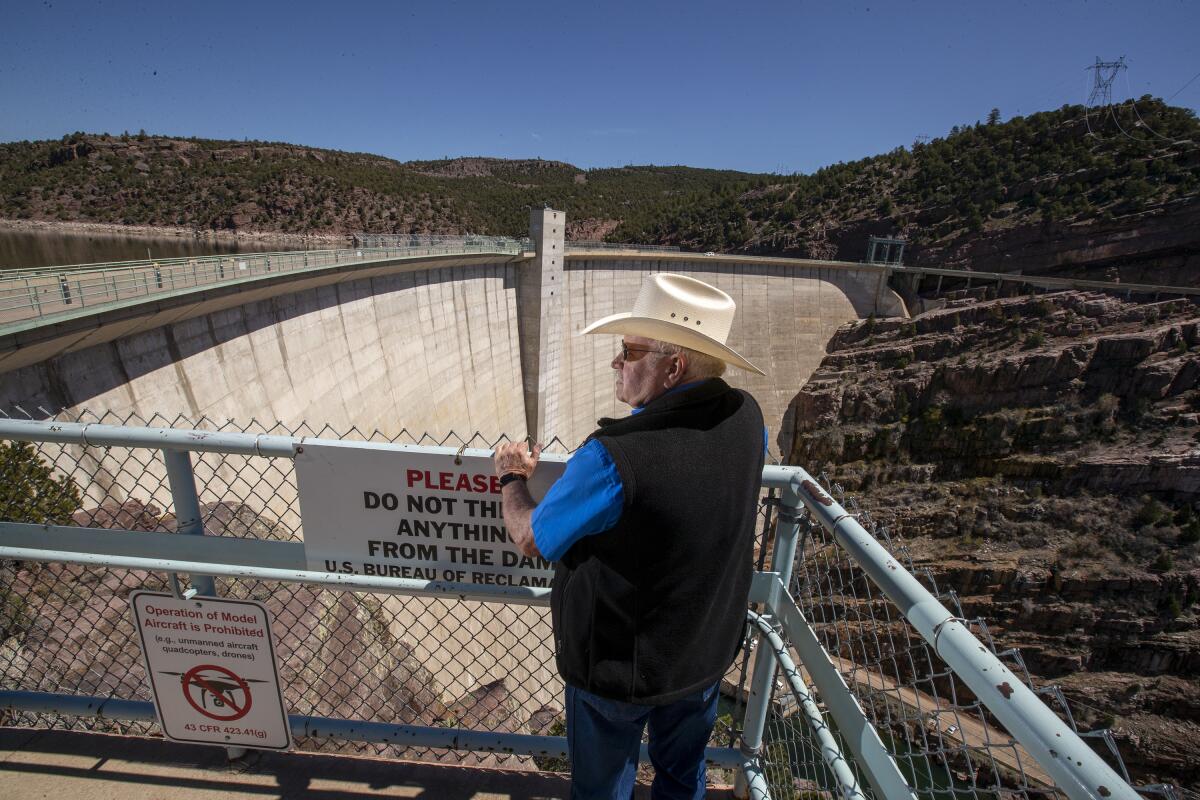

“It’s a beautiful dam. It’s a beautiful reservoir. It’s too bad we can’t share it,” Elbrock said.

A 32-year Bureau of Reclamation veteran with a cowboy hat and white handlebar mustache, Elbrock seemed pleased to show off the facility. As we stood at the foot of the dam, on the downstream side, he fetched some crackers and encouraged Rob and me to toss them to trout in the Green River below, where the nonnative fish swarmed to feed. He also talked about the intense flooding of 1983, when so much runoff flowed into the reservoir that he remembers water splashing onto the highway atop the dam.

Elbrock would love to see that much water pouring into the Green River again, although it doesn’t seem likely anytime soon. Before drought began punishing the West around the turn of the century, Flaming Gorge Dam typically generated more than 500,000 megawatt-hours of electricity each year. Over the last 20 years, it’s averaged more like 425,000 megawatt-hours.

The extra releases over the next year could boost hydropower production in the short term, with longer-term decreases as the reservoir drops. But really, what matters most to Western cities and farms is whether those releases are enough to protect Lake Powell. If Powell gets so low that Glen Canyon Dam can no longer generate electricity, an energy and water crisis could ensue.

“If the lake were to decline, that capacity to release water lessens,” Bureau of Reclamation official Daniel Bunk said at a meeting in Phoenix last week, as reported by my Times colleague Ian James. “There’s a lot of uncertainty with operating below that level.”

The water risks are straightforward: If the 40 million people and 5 million acres of farmland that draw from the Colorado River and its tributaries keep trying to use more water than is available, someone is going to lose out. A lot of someones, really.

The energy risks require a bit more explanation. Hydropower has long been a backbone of the Western power grid, with rivers from the Colorado to the Columbia fueling the growth of cities including Los Angeles, Phoenix and Seattle. And even as some environmental activists campaign to demolish certain dams and restore the ecosystems they destroyed, hydropower turbines have become an increasingly valuable tool for keeping the lights on after sundown, when solar panels stop generating electricity.

The threat of power shortages is real — especially on stiflingly hot summer evenings when the entire West is baking, and people have no choice but to keep blasting their air conditioners after sundown. Those are the kinds of conditions that prompted rolling blackouts in California in August 2020, with state officials warning that the potential for outages could be worse this summer.

California has been at the vanguard of this challenge — but it’s far from alone. As coal plants shut down and heat waves get worse, many states could have trouble keeping the lights on this summer, as Katherine Blunt reports for the Wall Street Journal.

Long term, there are plenty of ways to keep the lights on while phasing out fossil fuels, as I’ve written previously. Just this week, a unique new analysis concluded that California can reach 85% clean electricity by 2030 — up from 55% today — while maintaining a reliable electric grid. The key is quickly ramping up geothermal and offshore wind power, Jeff St. John writes for Canary Media.

But all the research I’ve seen suggests that continued use of hydropower will be needed to eliminate fossil fuels. For the West, one of the trickiest parts will be balancing energy needs with water needs. As Reclamation official Nick Williams reminded me this week when we discussed Flaming Gorge and other dams, “power is there because of the water — and not the other way around.”

“We only have a limited supply of water to drive these plants, and so we have to operate within limits,” he said.

Some of those limits are designed to protect fish, and reverse at least a smidgen of the harm dams have done to ecosystems and tribal cultures. At Flaming Gorge, a 2006 “record of decision” helps determine when water is released, with a goal of supporting four fish protected under the Endangered Species Act: the bonytail, Colorado pikeminnow, humpback chub and razorback sucker.

The extra releases to prop up Lake Powell may benefit the Flaming Gorge ecosystem a bit, by giving biologists more chances to test out strategies for supporting native fish and disrupting invasive species, as Chris Outcalt reports for the Colorado Sun.

But that kind of experimentation is a small mercy for rivers that dams have irrevocably altered. Sierra Club leader David Brower famously regretted striking a deal that allowed for the construction of Glen Canyon, Flaming Gorge and other reservoirs in exchange for protecting Dinosaur National Monument from a dam — a deal Brower called his “greatest mistake, greatest sin.”

Tinkering with water release schedules also doesn’t change the reality that there’s less and less water to go around in the West.

“This drought is unprecedented in modern times, but not unanticipated,” my L.A. Times colleague Corinne Purtill wrote last week, in a story meditating on the decline of Lake Mead. “In that [United Nations] report from two decades ago, the authors predicted that if we did nothing to halt climate change, we’d see exactly the kinds of conditions the West is experiencing now: higher daily average temperatures, more heat waves, longer and more frequent droughts, poorer water quality, and more forest fires.”

Corinne began her story by noting that human remains had just been discovered in a barrel as Mead receded, calling the news a “grimly apt” metaphor for “the uncomfortable truths this drought has laid bare.” The next day, more human remains were found.

“No one can follow the trail I have followed the last four days without catching the spirit of the West,” Lady Bird Johnson said on Aug. 17, 1964, when she dedicated Flaming Gorge Dam. “It has been the spirit of adventure which made bold pioneers and brave frontiersmen — the spirit of optimism which caused men and women to dream big and build big.”

Those Western adventurers — colonizers, some would call them — did all sorts of terrible things, such as massacring Indigenous Americans, stealing their land and wiping out buffalo and other wildlife. But they did dream big, just as we do today. Only today, we dream less about conquering Western landscapes and more about protecting them — from ourselves, and for ourselves.

“Americans have always felt that the tomorrow of our children should be better than the yesterday of our parents,” Lady Bird Johnson said at Flaming Gorge. “We share a faith in life that the best is yet to come, that we must build our future, not belittle it.”

Let’s keep the faith, if we can.

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

Support our journalism

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Subscribe to the Los Angeles Times.

Here’s what else is happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

With drought getting worse — California’s largest reservoirs are at critically low levels — it’s time for residents to step up their conservation game, officials say. So far, it isn’t happening; water use rose in March, possibly because of drought fatigue, my colleague Jaimie Ding reports. But new restrictions taking effect June 1 might change the game. Los Angeles will limit outdoor watering to two days per week, and other places are taking even more aggressive action, per The Times’ Hayley Smith. As much as homes were able to cut back on water use during the last drought, there’s still a lot more we can do, with Las Vegas and Israel offering possible models for further savings, Hayley and Ian James write. If you’re looking for advice, Jeanette Marantos explains how to keep your veggie garden alive while using less water, and how to take care of your lawn — or get rid of it. And if you’ve got advice of your own — or tore out your lawn — The Times wants to hear from you. Fill out this form and we’ll share your tips!

Prompted by an L.A. Times investigation into the water well-drilling frenzy in California’s San Joaquin Valley, a lawmaker is looking to strengthen oversight of groundwater aquifers. New legislation from state Assemblymember Steve Bennett, a Ventura Democrat, would block local governments from approving new wells unless the local groundwater sustainability agency signs off, Ian James reports. Here’s our original investigation from Ian, Maria L. La Ganga and Gabrielle LaMarr LeMee, which found that more than 6,200 agricultural wells have been drilled in the San Joaquin Valley since 2014. In another contentious water debate, Times columnist Steve Lopez urges the California Coastal Commission to reject a desalination plant in Huntington Beach.

Southern California regulators are blaming the federal government for not improving air quality fast enough. The region’s powerful but little-known South Coast Air Quality Management District is threatening to sue the Environmental Protection Agency for not doing more to slash pollution from airplanes, trains and ships, The Times’ Tony Briscoe reports. The district’s critics don’t necessarily disagree, but they say state and local officials could also be working harder to reduce emissions from cars and trucks. One reason that’s so difficult? Opposition from organized labor. As my colleagues Liam Dillon, Ben Poston and Rachel Uranga report, construction trade unions are opposing a bill that would block freeway expansions in heavily polluted neighborhoods, with one labor leader saying, “We’re not the organization of ‘no’ when it comes to climate change. We’re the organization of ‘slow.’”

POLITICAL CLIMATE

Under pressure from Gov. Gavin Newsom earlier this year, the California Public Utilities Commission shelved its December proposal to cut rooftop solar incentives, at least temporarily. Now the commission seems to be gearing up for a revised decision, announcing this week it will solicit additional public feedback on several key issues over the next month. It’s still far from clear what the agency will do next, though, as Canary Media’s Jeff St. John explains. In related news, Seth Rosenfeld wrote an important, thorough story for the San Francisco Public Press showing how the utilities commission systematically subverts public records law, fighting tooth and nail to keep information about wildfire safety, utility companies and more out of the public eye.

L.A. City Council ordered more testing for potential toxic waste at the site of a Lincoln Heights housing development, following a community uproar over possible gentrification and a history of illegal dumping. Here’s the story from The Times’ Jonah Valdez. Jonah also wrote about the tension that can exist between building more apartments near public transit — which the region desperately needs — and respecting the needs and desires of disadvantaged community residents, such as those in Lincoln Heights. In another conflict over housing, voters in the East Bay city of Martinez face a choice: Should they tax themselves to buy and protect the Alhambra Highlands, where the famed environmentalist John Muir owned a ranch and grew pears and apples? Or should they let a developer build homes on the property? The San Francisco Chronicle’s J.K. Dineen lays out the arguments.

Is there any chance of Congress passing a climate bill this year? My colleague Anumita Kaur takes a look, and offers a rundown of the clean energy policies in President Biden’s Build Back Better legislation, which has been blocked by 50 Republican senators and West Virginia Democrat Joe Manchin. The Atlantic’s Robinson Meyer isn’t optimistic, writing that the Democratic Party “doesn’t even seem to realize that it’s blowing a once-in-a-decade chance to pass meaningful climate legislation.” In California, meanwhile, regulators unveiled a draft five-year climate plan that activists say isn’t strong enough, as Nadia Lopez reports for CalMatters.

AROUND THE WEST

The actor James Cromwell glued his hand to a Starbucks counter to protest upcharges for dairy milk alternatives — and climate was on his mind. “Producing cow’s milk generates three times more greenhouse gases than producing vegan options,” Cromwell said in a live feed, my colleague Nardine Saad reports. At least in theory, climate pollution from dairies could be reduced; California just approved a new cattle feed designed to limit methane in cow burps, per the San Francisco Chronicle’s Tara Duggan. At the same time, methane isn’t the only environmental consequence from raising cows; cattle ranching can degrade habitat for at-risk wildlife such as the sage grouse, conservationists say. Speaking of which, sage grouse numbers have continued to fall across the West this year, raising the likelihood of Endangered Species Act protections, Scott Streater reports for E&E News.

New Mexico continues to burn, with a major fire scorching more than 370 square miles and growing 50 square miles in a single day. More details here from Susan Montoya Bryan at the Associated Press. In a bitter irony, that fire stems in part from a prescribed burn getting out of control. As Raymond Zhong writes for the New York Times, prescribed burns are meant to reduce fire risk, but climate change is making them more dangerous. It’s super unfortunate, especially in light of a new study finding that California’s destructive 2020 blazes were fueled in part by a history of fire suppression — the exact problem prescribed burns are supposed to help solve. Also unfortunate: Climate change appears to be weakening the coastal marine layer clouds that give Southern California its “May gray” and “June gloom,” potentially worsening wildfire danger, The Times’ Paul Duginski reports.

America’s National Conservation Lands don’t get a lot of love — but these 35 million acres are some of the most pristine and scientifically important areas overseen by the federal government, advocates say. If President Biden wants to protect 30% of U.S. lands and waters by 2030, boosting this program could help, Scott Streater writes for E&E News. A bill from Sens. Joe Manchin and John Barrasso, meanwhile, would lead to more parking spots, more target shooting and more internet access on public lands; the National Parks Conservation Assn. has some concerns, per Kyle Dunphey at the Deseret News. Elsewhere on public lands, Jimmy Carter filed a brief asking a court to overturn a Trump-era land exchange that would allow a road to be built through an Alaska wilderness area. It’s an unusual move for a former president, Mark Thiessen writes for the Associated Press.

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

Stanford University got a $1.1-billion donation to open a climate and sustainability school. The money comes from venture capitalist John Doerr and his wife Ann, with energy systems expected to be a major focus, my colleague Colleen Shalby reports. While the news generated plenty of excitement in academic and environmental circles, I also saw an undercurrent of skepticism given that the climate school will work with — and accept donations from — fossil fuel companies, and that its inaugural dean has helped lead an energy institute named for veteran oil executive Jay Precourt. More discussion here from Protocol’s Brian Kahn.

The San Jose solar manufacturer whose tariff petition has thrown the brakes on the U.S. solar industry produces panels that may be defective. And it’s not producing nearly as many panels as claimed, according to Canary Media’s Eric Wesoff, who has been investigating Auxin Solar. Climate advocates say the Commerce Department’s investigation into Auxin’s tariff petition has compounded the pain of President Biden’s failure to deliver on key climate promises, Dan Gearino writes for Inside Climate News. In other federal news, the Biden administration won’t require electric water heaters in new commercial buildings — but its rule mandating more efficient gas water heaters is still facing pushback from the gas industry, per Miranda Willson at E&E News.

The growth of solar power has prompted San Francisco to release less water through its hydroelectric generators in the Tuolumne River when the sun is shining — with the side effect of making it harder to raft down the river during daylight hours. The smaller amounts of water flowing through the Tuolumne have created a challenge for rafting guides, with one telling the San Francisco Examiner’s Jessica Wolfrom, “I can’t really put flashlights on the handles of paddles.”

ONE MORE THING

Warning: This section contains spoilers for “Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness.” Consider yourself warned!

Between the climate crisis, numerous wars and many other injustices, we live in grim times. So grim, in fact, that moviegoing audiences “may be uniquely willing to imagine worlds within worlds that could have gone differently in incalculably varied ways,” writes Ryan Faughnder in our Wide Shot newsletter, while discussing the alternate realities portrayed in the latest Marvel film.

Ryan has a point. Personally, I was intrigued by the eco-friendly version of New York City that Benedict Cumberbatch and Xochitl Gomez wander through in the “Doctor Strange” sequel, with greenery everywhere and little streams flowing through the city.

You could call that escapist fantasy, but I prefer to think of it as inspiration. If we’re going to solve the problems we’ve created — including climate change — it can start with envisioning a world where we’ve made good choices, and working backward from there. Even if there’s only one future out of millions where everything works out, it’s a future worth imagining — and fighting for.

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.