- Share via

When Shasta Dam was built on the Sacramento River in the 1940s, the government also established Coleman National Fish Hatchery about 30 miles away on the tributary Battle Creek, aiming to make up for the loss of upstream habitat by raising fish for release.

The hatchery’s staff runs an elaborate spawning operation that this year is raising 12 million fall-run Chinook salmon, supporting California’s commercial and recreational fisheries. The hatchery also raises other types of salmon and steelhead.

The adult salmon swim up the Sacramento River and into Battle Creek, then up a fish ladder to the hatchery’s holding ponds. Mechanical screens in the water are used to move the fish to the spawning building.

The fish are placed into a bath with carbon-dioxide in the water, which enables the staff to handle them. Workers lift the salmon from the water in nets, check to see that they’re ready for spawning, and separate females from males.

They club the fish and send them sliding down a metal chute. One worker hangs each female salmon from a hook, inserts a needle in its abdomen and sends air flowing to push out the eggs, which land in a colander. Another worker grabs each male fish and twists the tail, squeezing out milt that will fertilize the eggs.

“We’re here to support the fishery,” said Brett Galyean, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s project leader. “Without the hatcheries, there probably wouldn’t be much fishing or any fishing in the Sacramento River.”

At the base of Shasta Dam, a different sort of spawning operation at Livingston Stone National Fish Hatchery focuses on boosting the population of the endangered winter-run Chinook salmon.

The winter-run salmon are captured in a trap at the base of Keswick Dam, loaded onto a truck and driven to the hatchery. Each winter-run Chinook is genetically tested and given a number, and each pair of male and female is selected. After spawning, the tiny fish are raised until they’re large enough to be released in the Sacramento River.

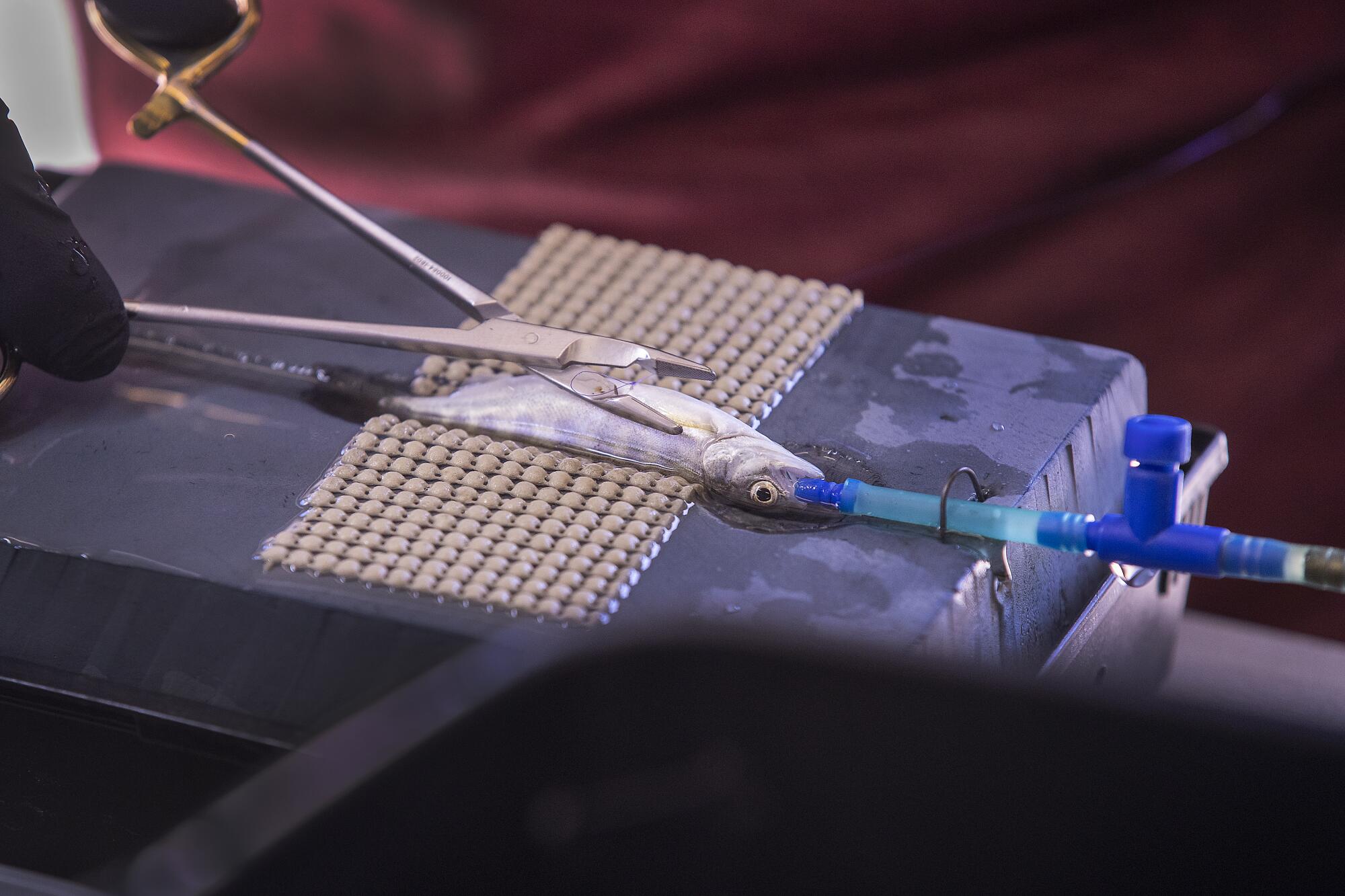

Several hundred winter-run Chinook also have tiny transmitters inserted by hand. This operation was performed on recent afternoon by Arnold Ammann, a biologist with the National Marine Fisheries Service.

Wearing black gloves, he lifted a finger-sized salmon from a bucket and laid it on a padded mat. The salmon was stunned with an anesthetic and lay motionless.

Ammann cut an incision in the abdomen and inserted the cylinder-shaped transmitter, called an acoustic tag. The device emits a high-frequency signal, enabling scientists to track the fish’s movements as they swim to the Pacific Ocean.

“They heal up pretty quickly,” Ammann said. “It has a minimal effect on them, and we can get good information on their movement and survival.”

Related: California salmon are at risk of extinction. A plan to save them stirs hope and controversy