For black Americans, Trump’s ‘shithole’ comment was an insult to their histories

- Share via

Reporting from Atlanta — The president’s question was this: “Why are we having all these people from shithole countries come here?”

Technically — in its own crass way — it was a policy question. Specifically, President Trump was asking why the U.S. should accept immigrants from Haiti, El Salvador and African nations instead of immigrants from wealthy Norway, according to reports of the president’s remarks to congressional lawmakers at a Thursday meeting.

Yet for many black Americans, the president’s remarks, as so many times in the past, seemed to draw a bull’s-eye on their skin color.

As they saw it, the president was essentially asking that government policy prioritize white foreigners over black and brown foreigners.

And beyond policy, for many black Americans, “shithole countries” was not just a diplomatic insult to several foreign nations. It was a deeply personal insult to the stories and histories of how their own parents and ancestors immigrated — or were kidnapped and forcibly trafficked — to the U.S.

“They just worked and worked and worked my whole life,” Ike Ndolo, 34, of Phoenix said Friday, recalling what it was like to grow up in Columbia, Mo., as the son of two parents from Nigeria — immigrants from one of Trump’s “shithole countries.”

Ndolo’s father immigrated to the U.S. 36 years ago for college and earned a master’s degree in engineering at the University of Missouri. His mother, while eight months pregnant, followed him to the U.S., where she would go on to work in day-care, caring for other Americans’ children.

“Seeing my parents struggle, and seeing the comments yesterday … I think I’ve been angry since last November, [but] this was especially outrageous,” said Ndolo, a musician.

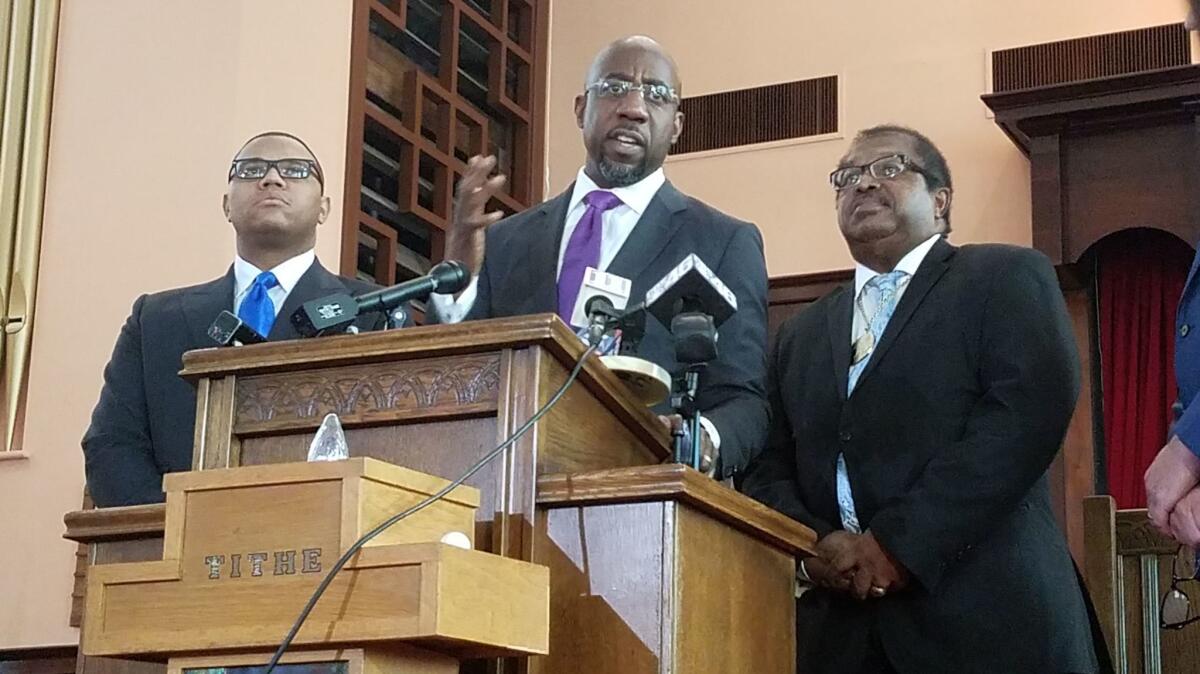

On Friday in Atlanta, an interfaith coalition of religious leaders took to the pulpit of the Ebenezer Baptist Church, where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was baptized as a child, to condemn Trump’s statements on the eve of the King holiday weekend.

The Rev. Timothy McDonald, pastor of the First Iconium Baptist Church in east Atlanta, wondered about people who heard Trump’s remarks.

“What concerns me is the silence of all the other people, the other people who were in the room,” McDonald said. “Where are their voices? The other senators who sat there and listened. What did they say? What did they think?” (Though Trump tweeted Friday that he did not say “shithole,” some senators said he did, while other senators said they didn’t recall the comment.)

The Rev. Raphael G. Warnock, senior pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church, who believes his ancestors came to the United States as slaves from Cameroon in central Africa, said that Trump’s comments were deeply personal.

“I serve as pastor at a church that is filled with people from far corners of the globe, certainly from throughout the African diaspora,” Warnock said in an interview. “I mean, where would America be without its African descendants? There would be no jazz, the only original music coming from America. There would be no blues. We wouldn’t have the genius of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. without reference to the African continent.”

Kimberly Atkins, the Washington bureau chief of the Boston Herald, recently did a DNA test “that pretty much confirmed my heritage is 100% the result of the slave trade,” she wrote in a private message on Twitter. “Eighty-seven percent from western coastal African countries and 13% European, all migrated by way of the American South.”

She traced part of her heritage to an ancestor who fought in the Union during the Civil War to guarantee his freedom and the abolition of the U.S. slave trade. “My ancestors did not come from shithole countries,” she tweeted. “They were neither tired nor poor. They were forcibly brought here to live in a shithole created for them.”

Trump’s singling out of Haiti was particularly frustrating for descendants from the Caribbean nation, coming as the nation mourned the eighth anniversary of an earthquake that killed hundreds of thousands of residents.

“Haiti is not unacquainted with racists or white supremacists. We defeated our share of them in 1804 when we became the world’s first black republic,” Haitian American author Edwidge Danticat wrote in a post on Facebook, expressing her frustration that Haitians’ mourning was being diverted by an insult from Trump.

Danticat’s father came to Brooklyn, N.Y., to drive a taxicab “sometimes sixteen hours a day, so that my three brothers (two teachers and an IT specialist) and I could have a better life,” Danticat wrote.

Danticat added: “We are also the country that the United States has invaded several times, preventing us from consistently ruling ourselves. If we are a poor country, then our poverty comes in part from pillage and plunder.”

Clint Smith, a writer and PhD candidate Harvard University specializing in sociology and education, said that he hoped that at least the president’s remarks would prompt a fuller conversation about past U.S. and European involvement with the countries Trump mentioned — countries still troubled by the legacy of colonial rule and military interventions.

“You can’t understand the economic conditions in which Haiti exists now without understanding the centuries and centuries of direct imperialism and violence and economic exploitation that the country experienced after the Haitian revolution of 1804,” Smith said. “We can’t have a real conversation about what is happening, why Salvadorans are coming here, without discussing how the U.S. contributed to the civil unrest in that country.”

The larger conversation, Smith said, “is not often enough taking into account the way that U.S. policy directly contributed to the condition in which so many of these so-called shitholes are currently existing.”

Matt Pearce is a national reporter for The Times. Follow him on Twitter at @mattdpearce.

Pearce reported from Los Angeles and special correspondent Jarvie from Atlanta.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.