Editorial: After Theresa May’s humiliating Brexit defeat, it’s time to send the referendum back to a vote

- Share via

British Prime Minister Theresa May suffered a humiliating, historic defeat on Tuesday when the House of Commons refused to approve the voluminous Brexit agreement she painstakingly negotiated with the European Union. The 432-202 margin was even more lopsided than some had expected, and led to a motion by Labor Party leader Jeremy Corbyn for a vote of no-confidence in her government that will be debated on Wednesday.

May is expected to survive that challenge. But Tuesday’s vote will make it difficult for her to salvage the idea of a carefully negotiated withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union. She is free to seek further concessions from the EU, but European leaders have little incentive to offer any. So far, they have resisted making significant changes in the deal, including in the controversial provisions affecting Northern Ireland. After the vote in Parliament, European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker said: “I urge the United Kingdom to clarify its intentions as soon as possible. Time is almost up.”

If nothing is done, the U.K. will move inexorably toward a “no-deal Brexit,” a nightmare scenario in which it leaves the EU in March without the cushion of transitional trade arrangements with Europe and measures to prevent the reestablishment of a hard border between Northern Ireland, a U.K. province, and the Republic of Ireland. Such an outcome would send shock waves through the British economy.

Brexit was never going to be a simple process. And once the concept of “Leave” was replaced by a detailed blueprint, opposition inevitably arose.

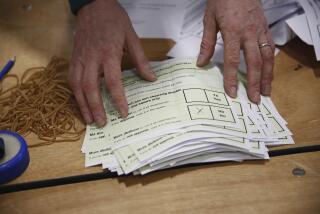

But there remains the possibility of another, more hopeful, alternative: a new referendum — a rerun, in effect, of the June 2016 vote in which British voters chose to leave the EU with what it now seems obvious was an insufficient understanding of the consequences of such a drastic step.

May is being criticized for failing to convince members of Parliament, including some former members of her own government, about the merits of the deal, particularly a “backstop” provision that, under some circumstances, could allow rules to be imposed on Northern Ireland that wouldn’t apply to the rest of the U.K. That disparate treatment was anathema to so-called Unionists in Northern Ireland who have supported May’s government and also to some members of her Conservative Party. (Ironically, as long as the U.K. remains in the EU, Northern Ireland is treated the same as England, Scotland and Wales.)

Perhaps the prime minister could have been more persuasive in lobbying her colleagues or winning additional concessions from Brussels. But the truth is that, given decades of integration between the U.K. and the rest of Europe and the importance of the Northern Ireland peace process, Brexit was never going to be a simple process. And once the concept of “Leave” was replaced by a detailed blueprint, opposition inevitably arose.

The 52% of voters who supported “Leave” in 2016 might have thought that withdrawing from the EU would be a simple proposition. Scandalously scant attention was paid, for example, to the implications of Brexit for the Northern Ireland peace process. (The fact that both the U.K. and the Republic of Ireland were members of the EU contributed significantly to the easing of tensions between north and south and between Catholics and Protestants within Northern Ireland.)

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute »

Since the vote, however, it has become clear that disentangling the U.K. from the EU is a complicated economic and political undertaking with the potential to create massive disruption in the lives of ordinary British people. That’s why May was so determined to negotiate a detailed agreement for an orderly withdrawal. So far, her efforts have been unsuccessful.

Rather than getting swept along into a “no-deal” Brexit, her government should seriously explore the possibility of giving the voters an opportunity to revisit the basic issue now that the practical and political difficulties of implementing Brexit have been made clear.

European leaders have indicated that they would be willing to extend the March 29 deadline for the U.K.’s withdrawal from the EU. Delay could allow for further negotiation on a withdrawal agreement that might win the support of a majority in Parliament, but it could also allow the needed time to call another “people’s vote.” Willingness to admit a mistake is a virtue in individuals; it also reflects well on a nation.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinionand Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.