Op-Ed: Mike Huckabee’s rhetoric of religious victimization

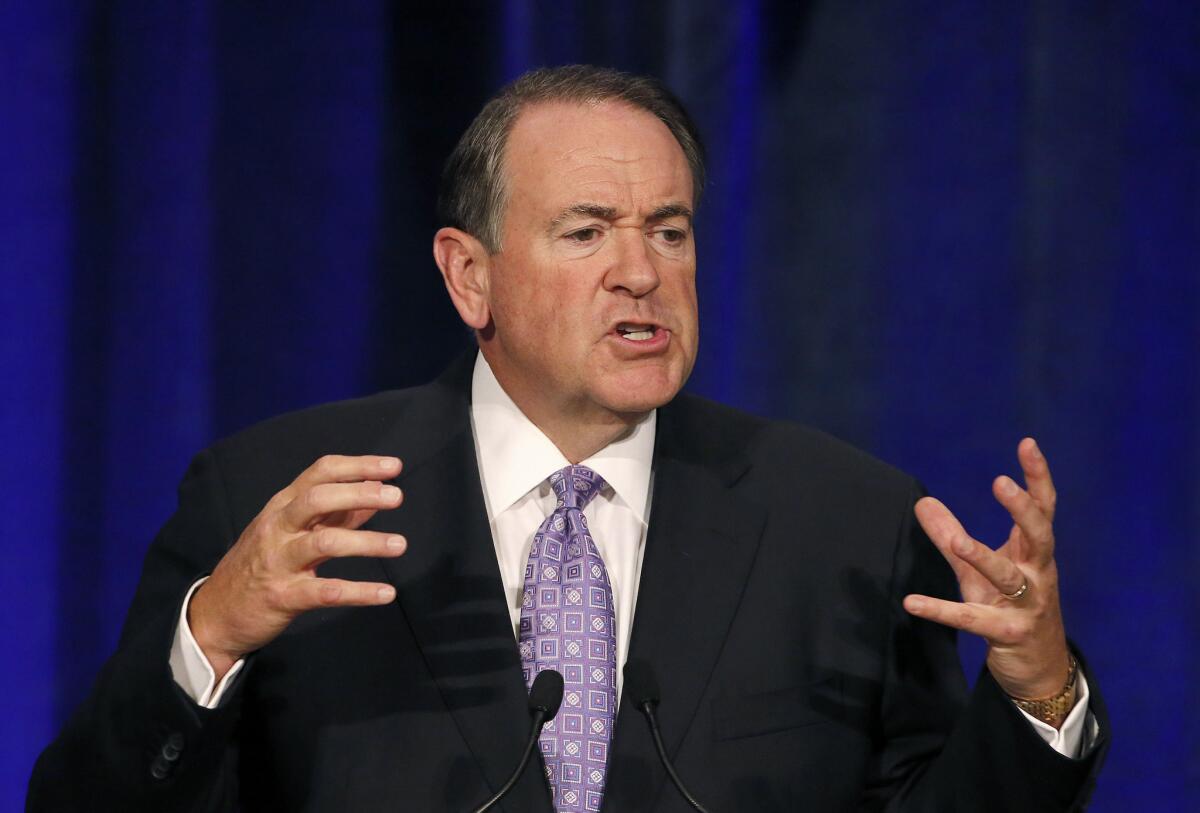

Mike Huckabee in Scottsdale, Ariz. earlier this month.

- Share via

Just prior to announcing his candidacy for the Republican presidential nomination, Mike Huckabee addressed the Iowa Faith and Freedom Coalition in Waukee. “We are criminalizing Christianity in this country,” Huckabee declared. “We cannot stand by silently.” The Southern Baptist minister, former governor of Arkansas and Fox News host went on to sympathize with those who are “scorned” or “mocked” for what they believe and suggested that they might be jailed. “That’s the fear that we better face,” he concluded.

Most voters outside of Republican primaries will find these assertions less than persuasive, even paranoid, but also, perhaps, familiar. With his entry into the race, Huckabee is bringing back into the national political conversation the sounds and tropes of the religious right. Whereas the tea party, which has come to dominate the grass-roots movement, broadcasts anger, the religious right stresses victimization.

Huckabee’s statement in Waukee was eerily reminiscent of the sentiments I encountered among activists on the religious right in the run-up to the Iowa caucuses in 1988. At that time, Iowa’s evangelicals were still relatively new to the political process, still learning the ropes. But they were already fluent in the language of ill-treatment.

“The enemy would just come in like a flood if we didn’t stand there,” one activist told me.

For much of the 20th century, America’s evangelicals felt marginalized. They hunkered into a subculture of their own making — congregations, denominations, Bible camps, Bible institutes, private colleges, seminaries — to protect themselves from the depredations of an outside world that they believed was both corrupt and corrupting.

When they emerged into the political arena in the late 1970s, enraged by the rescission of tax-exempt status for segregated schools and later galvanized by opposition to abortion, they came to believe that their values were under attack. Despite their numbers and their growing political influence, they still felt, in Huckabee’s words, scorned and mocked.

By the 1980s, abortion was the issue that politically conservative evangelicals talked about most — and they did so in terms that suggested an almost preternatural identification with the innocence and the vulnerability of the fetus.

“The most dangerous place to be these days,” the president of the Iowa chapter of Concerned Women for America told me in 1988, “is inside a mother’s womb.”

An antiabortion radio commercial airing around that time began: “First we had abortion, and they said that was all they wanted.” The ominous voice continued: “Then we had infanticide, killing handicapped newborn babies. Now we have euthanasia, killing the elderly and sick.” Then, after a pause: “Will you be their next victim?”

“They” and “their” were never specified, and the radio spot offered no evidence of infanticide or euthanasia. But the rhetoric of vulnerability need not be accurate to be effective.

Huckabee is deploying the same sort of rhetoric now as he advances his presidential prospects and tries to mobilize conservative evangelicals.

Whereas a candidate such as Sen. Rand Paul of Kentucky worries about personal liberties, Huckabee warns about religious persecution. “I came to New Hampshire to announce that I will fight for your right to be left alone,” Paul declared at the beginning of his campaign.

Huckabee’s approach is less philosophical and more visceral. “I think it’s fair to say that Christian convictions are under attack as never before, not just in our lifetime, but never before in the history of this great republic,” Huckabee told pastors on an April conference call arranged by the Family Research Council.

Of course, Huckabee’s linguistic style is part and parcel of his political strategy. In his 2008 book, “Do the Right Thing,” Huckabee noted that whenever the religious right “was energized and turned loose, they made the difference in elections.” Conversely, “when the GOP somewhat put us back in the attic and out of the way, we lost.”

Huckabee’s argument to Republican primary voters is that the religious right, beginning with Ronald Reagan and continuing with George W. Bush, has a better track record of electing presidents than the tea party. When politically conservative evangelical voters have been indifferent about the Republican nominee — George H. W. Bush’s run for reelection in 1992, John McCain in 2008, Mitt Romney in 2012 — the party’s fortunes have faltered.

At yet another event in Iowa last year, Huckabee took aim at those within his party who want to avoid social issues. They only want to talk about “liberty and low taxes,” he complained.

The anger of tea party activists, in Huckabee’s assessment, might attract media attention, but blind fury tends to be more evanescent than moral passion or the conviction that your values are endangered.

This is the sentiment that lies behind the so-called religious-freedom laws making their way through Republican-dominated state legislatures — laws that would allow individuals and businesses to refuse service on the basis of religious convictions. Our values are under attack, they insist. Huckabee warns darkly of incarceration.

Huckabee’s own path from the attic back into the mainstream of presidential politics will not be easy. Resuscitating the rhetoric of victimization that religious right voters found so compelling in the 1980s, he must persuade them that their way of life is under siege. His electoral prospects may ride on his success in doing so.

Randall Balmer, an Episcopal priest, is chairman of the Religion Department at Dartmouth College. His most recent book is “Redeemer: The Life of Jimmy Carter.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.