Op-Ed: ‘Just to be safe’ is exactly the wrong reason to get a medical test

- Share via

In tennis parlance, I had my friend Stewart on a yo-yo, pushing the ball from side to side, front to back, forcing him into ever more desperate, lung-searing wind sprints just to stay in the point. On the penultimate exchange, I gently slid the ball rightward into the open court, convinced he’d never recover in time. After all, we’d been playing for more than two hours, and he was red-faced, gasping for air. And yet, recover he did. With a thunderous groan, this 56-year-old former collegiate linebacker lashed at the ball, driving it down the line for a winner. I didn’t even move.

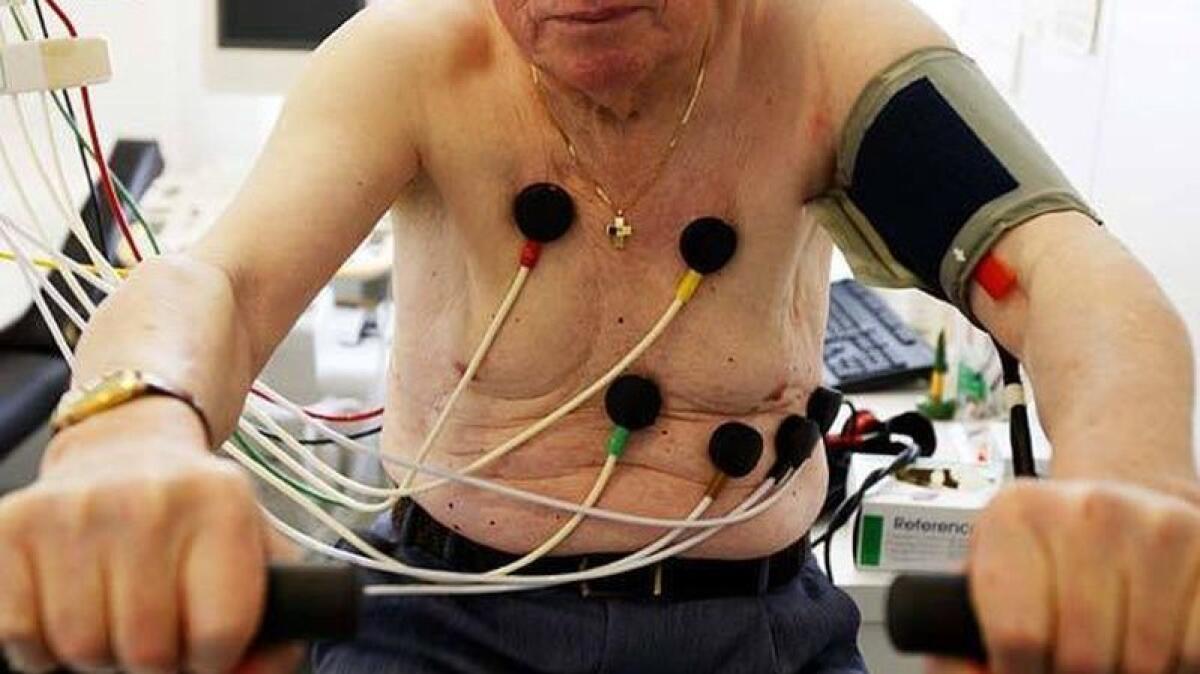

I’m telling you this story because a few minutes later, at courtside, he asked me a question that surprised me. “My doctor sent me to a cardiologist, and the guy wants me to do a treadmill test to rule out heart disease. What do you think?” Stewart’s father had died of a heart attack during his 60s. His family doctor and the specialist told him to have the test “just to be safe.”

“That’s ridiculous. You have the heart of a lion,” I told him.

I’m not Stewart’s doctor. I haven’t examined him or his medical records. And I’m not a cardiologist. But I wasn’t being cavalier either. I’ve been an emergency room physician for 30 years. He told me that his blood pressure and cholesterol numbers were good. And I knew that he’d never complained of chest pain or shortness of breath despite exercising vigorously five times a week. A first-year medical resident would have concluded what I did: Stewart didn’t have heart disease.

To be specific, even with a dad who died young of heart disease, a patient with Stewart’s qualities would have a roughly 4% risk of developing cardiac symptoms, and a 1% risk of death from heart disease, over the next 10 years. Despite Stewart’s fears, he had a 99% 10-year survival rate, before testing was even suggested.

But when a doctor’s recommendation comes with the phrase “just to be safe,” it is hard to ignore. So Stewart got his treadmill test. He passed with flying colors, lasting more than 18 minutes with no problems or changes on his cardiac monitor. Most healthy people can do only eight minutes.

Stewart’s situation made me realize how much I wish doctors would banish “just to be safe” from their lexicon. It contributes to the well-documented overtesting problem in American medicine. And overtesting not only increases healthcare costs; it actually exposes patients to unnecessary risks.

The most talked about triggers of overtesting in American medicine are profits and liability. Doctors face few barriers to ordering tests, which are generally perceived as efficient, remunerative and a safeguard when it comes to avoiding or winning lawsuits. But I think the overtesting phenomenon is more complicated than that. It’s rooted in a medical system that pushes doctors and patients to unconsciously reinforce each other’s weaknesses.

The harried doctor, short on time, may see testing as a way to bypass the hard work of explaining healthcare decisions to patients. Patients, encouraged by drug and healthcare marketing, may have unreasonable expectations about what medicine can offer. In this context, “just to be safe” can serve as cover, conveying a reassuring sense of caring and patient advocacy on the part of the doctor while also implying, de facto, that the benefits of testing outweigh the dangers.

But maybe I am being unsympathetic here. Patients like Stewart worry. In turn, doctors see themselves as patient advocates. Why not do the treadmill test? In a word, because medical tests can lie. They may over-call the presence of a particular condition or miss it entirely. They are far from perfect.

The accuracy of any test depends on the likelihood that the patient has the disease in question — before the test is performed. The lower this pre-test probability, the more likely a positive result will be a false positive. If you have a small chance of having the disease in the first place, testing is likely to do more harm than good through a combination of misinformation, additional testing, unnecessary treatment that can carry its own dangers (think surgical procedures, chemotherapy) and unnecessary costs.

For my friend Stewart, how did this play out? Studies show a treadmill test correctly identifies roughly half of patients who have coronary heart disease (that’s right, missing the other half altogether), and it is positive in about 15% of patients who have no coronary artery disease at all. Stewart’s negative result merely confirmed what was already known; a positive test would have been an almost guaranteed false alarm.

Stewart’s doctors surely knew all this, but they also knew that while his chance of having heart disease was tiny, it wasn’t zero. Testing seems to offer certainty, comfort that all avenues have been pursued. A normal test can be celebrated as “good news”; an abnormal test that is shown by more testing to be spurious is brushed off because “we got to the bottom of this and everything is OK,” ignoring the inconvenient truth that the initial test might have been avoided entirely.

To solve the problem of overtesting, we have to realign doctors’ incentives toward better outcomes rather than simply more care. That’s an existential challenge, but in the meantime, both players in the drama can go through a checklist. What are the likelihood and the consequences of a given disease for me/this patient? Does testing make sense given the pre-test probabilities of the disease? How corrosive is my/the patient’s worry?

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute from L.A. Times Opinion »

The “just to be safe” paradigm virtually ensures that none of this will get done. It also turns us away from logic toward irrational uncertainty and dependency. It seems like patient-centered care, but it actually ignores the unique circumstances and values of each patient.

Maybe you can guess what Stewart did next. The treadmill test, while negative, left a sliver of uncertainty. He underwent more testing: A nuclear medicine test came back with a small spot — probably an artifact but possibly something real. Finally, a coronary angiogram was performed and was normal, earning him an A grade from his cardiologist and a discharge to resume his weekly battles with me on the tennis court.

Stewart’s odyssey took three weeks and cost thousands of dollars, even after insurance. It filled him with anxiety. And it put him at a higher risk of a medical event than doing nothing at all. “Just to be safe” in this case meant staying out of the way of modern American medicine. To stay healthy, for now, my friend needed only a tennis racquet.

Dr. Eric Snoey is vice chair of emergency medicine at Alameda Health System-Highland Hospital in Oakland.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinionand Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.