Editorial: Beyond Bruce’s Beach is the tarnished American dream for Black Americans

- Share via

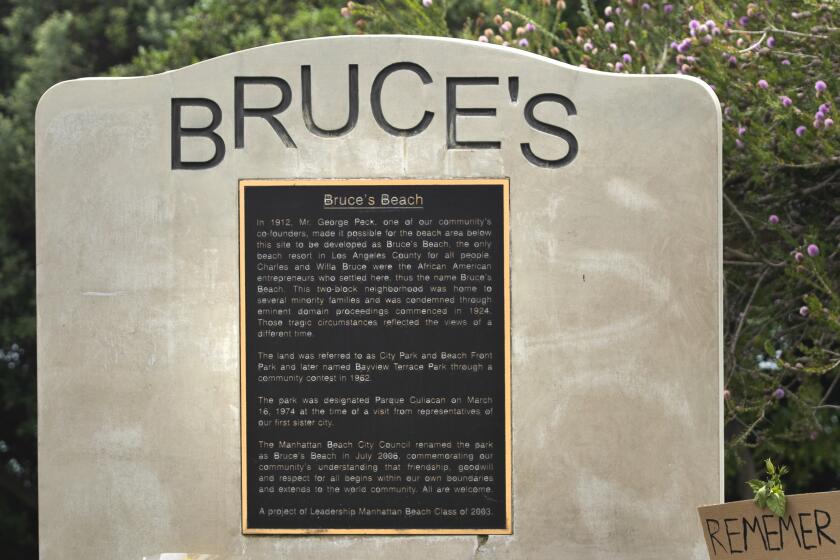

The significance of the Bruce’s Beach saga should not be underestimated or mischaracterized. The unfolding series of events that will return the Manhattan Beach property to the family that purchased it, built it into a thriving business venture and then lost it to anti-Black bigotry nearly a century ago is a mark not merely of some new progressive consciousness but of solid, time-tested American values.

When Willa and Charles Bruce purchased the beachfront property in the early years of the 20th century and built a resort that catered to Black residents, they were adhering to very conservative principles of citizenship and success: Invest. Better your circumstances. Work hard. Build a business, and know and serve your customer base. Build a legacy based on a store of family wealth that may enrich future generations.

It is the American creed and the American dream.

For the Bruces and countless other Black Americans, adhering to that creed and following that dream were undermined not by creeping socialism or foreign attack but by the cancer of racism, which grew side by side with the founders’ assertion that all men are created equal.

This return of property in Manhattan Beach should be seen as the beginning of a program to make reparations to correct injustices of the past.

The property belonging to the Bruces and other Black residents who owned land nearby was condemned when the white leaders of Manhattan Beach ostensibly discovered that they had insufficient public space and decided to seize Black-owned land to create a park.

Eminent domain and forced sales are among the banes of conservative thinkers who caution against governmental intrusion into private ownership. Had the Bruces and their neighbors been white, they could have counted on support from property rights advocates. But racism turns everything on its head, and the Bruces’ right to own land free of undue government intrusion was swept aside — just as it was elsewhere in California for Americans of Indigenous, Chinese, Japanese and Mexican descent, in one form or another, in the latter part of the 19th century and through much of the 20th.

The Bruces sued for compensation, which is another very American response to injustice. But they were awarded only a small portion of the land’s value.

The family that could have sprung from a Horatio Alger story (again, if it were white) and that might have built a resort empire lost its economic legacy but was not completely erased from history. Stories lingered. Books on local history and race included sections on Bruce’s Beach. The Times wrote about it in 2002. Manhattan Beach finally named the park for the Bruces in 2006.

The return of my family’s land will let us do what countless American families have done since our country’s founding: inherit property and build wealth.

But little of substance changed until the May 2020 killing of George Floyd and the racial justice protests that followed. Times staff writer Rosanna Xia wrote about the injustice visited upon the Bruce family, and this time, her deeply reported and engagingly written stories fell on attentive eyes and ears. The land had passed from Manhattan Beach to the state to Los Angeles County, and Supervisor Janice Hahn made restoring the property to the Bruces a priority. Transferring public land to private parties — in essence, reversing eminent domain — was not permitted under California law, and state Sen. Steven Bradford (D-Gardena) wrote and shepherded a bill to make the necessary changes. Gov. Gavin Newsom signed it into law last week.

The county operates a lifeguard training center on the property and will (in consultation with the Bruces) determine how to proceed. The title of the land most likely will be transferred, with the county paying fair market rent to its new landlords.

Compensation, consideration or damages for property unfairly confiscated by government, or for other injustices committed in government’s name, is also a bedrock conservative principle — just like pulling oneself up by one’s bootstraps — even when we use the word “reparations” instead of all those other terms.

California has a reparations task force to consider proposals for Black Americans. It has a special focus on compensation for descendants of people who were enslaved, but its purview goes beyond that, in recognition of losses incurred after emancipation. The Bruce family experience exemplifies just such post-slavery loss.

Any such attempt to right past wrongs should take a cue from truth and reconciliation commissions around the globe. First comes truth: an honest account of a city’s or a state’s or the nation’s government betraying its values and its creed to the detriment of a person or community. Reconciliation is at the far end of the process and can never be guaranteed. In between is reparation — or repair, restoration or some other process to compensate Americans for things improperly taken from them by a government grounded in the rule of law.

Of course Manhattan Beach and Los Angeles County should return Bruce’s Beach to the family from which it was wrongly taken, or else pay for the land. This kind of acknowledgement and reparation necessarily raises all kinds of questions about thefts from others, including land from indigenous Californians and labor and dignity from Black Americans, but the controversy over those questions is no reason to slow redress for the historically recent racist taking of the Bruces’ land.

The notion is unsettling when the damage done is intergenerational, as in the case of the Bruces. We are, after all, a nation that acknowledges the rights of individuals rather than families or communities. Besides, it is impossible to determine with any degree of certainty what a great-great-grandparent’s nest egg would have become had it not been unfairly grabbed by government.

But all individuals, even if created equal, proceed in life based at least in part on the blessings bestowed on them by their forebears. And if we can identify part of a legacy that we (because every American is a participant to some degree in our democratic government) unjustly took away, the least we can do is give it back if it is within our power.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.