George Floyd’s death in Amy Klobuchar’s home state renews scrutiny of her criminal justice record

- Share via

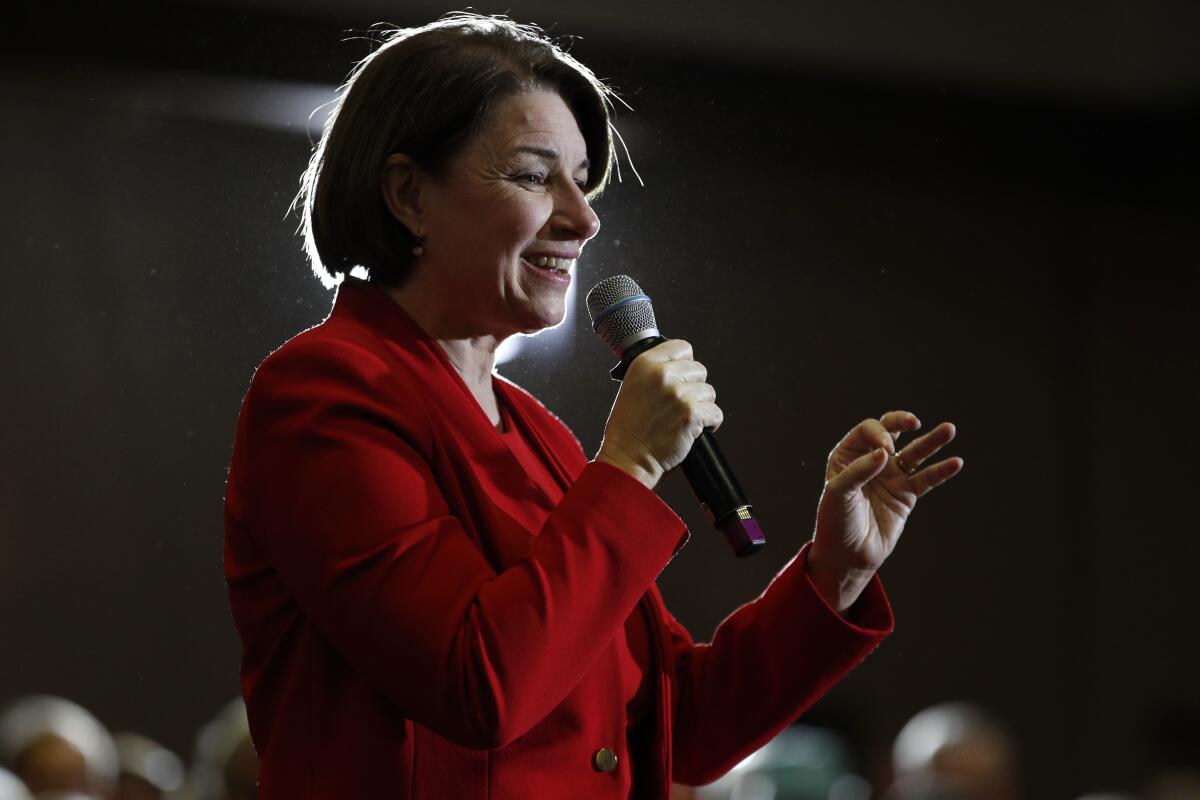

Amy Klobuchar has long been seen as a top contender to be Joe Biden’s running mate, albeit with a glaring liability: her weak standing with black voters, a core Democratic constituency.

That vulnerability became even more acute this week after George Floyd, an African American man, died after being pinned to the ground by police in Klobuchar’s home county. The death highlighted once again her record as a prosecutor and sharpened questions of whether the Minnesota senator would be the best choice in this moment of national racial anguish.

“She would be the absolute worst pick at this point,” said LaTosha Brown, co-founder of the group Black Voters Matter, adding, “In light of what is happening now, it would be an absolute slap in the face of black folks. And the party will pay dearly for that.”

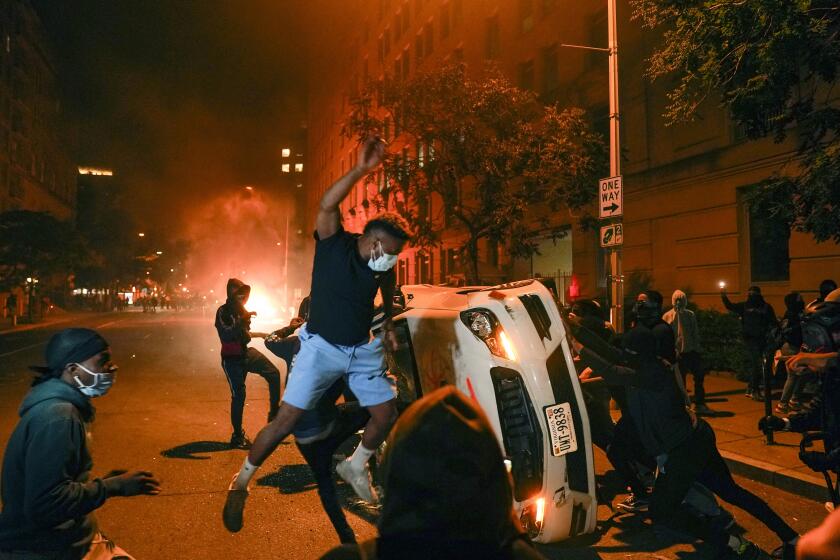

Floyd was videotaped as he gasped for air while handcuffed on the ground with a Minneapolis policeman pressing his knee into his neck for about eight minutes as three other officers looked on. His death Monday sparked days of destructive protests locally and across the country. Activists describe a black community at a breaking point, frayed by the recent high-profile police killings and violence and threats from white Americans captured on video, as well as bearing the disproportionate brunt of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“If George Floyd’s death has any legacy — because he will never be brought back — it should be systematic change to our criminal justice system,” Klobuchar said in an MSNBC interview on Friday.

She demurred when asked whether she should withdraw from consideration for vice president, calling it “Joe Biden’s decision.”

In an interview Friday on MSNBC, Biden dodged a question about whether Klobuchar’s record disqualified her as a vice presidential pick. “What we’re talking about today has nothing to do with my running for president or who I pick as vice president, it has to do with an injustice we all saw take place,” Biden said.

U.S. Rep. James E. Clyburn of South Carolina, one of the most influential voices in the Democratic Party, told reporters that Klobuchar’s chances probably had diminished in light of the upheaval in Minnesota.

“This is very tough timing for Amy Klobuchar, who I respect so much,” he said. “The timing is tough.”

Some of Klobuchar’s backers see her as an unfair target for anger over the killing.

“She had nothing to do with that officer putting his knee on this young man’s throat and killing him,” said Cordelia Lewis Burks, a longtime African American political activist and current vice chairwoman of the Indiana Democratic Party.

Lewis Burks, who favors Klobuchar’s pragmatic approach, said that many Democrats have had to acknowledge changing attitudes about criminal justice issues. As time passes, she said, “there is the chance to look at your record and say, ‘This was not what I should have done; I wish I had done something else.’”

Demonstrators break into a Minneapolis police precinct station after the department abandoned it, setting it ablaze, as protests spread nationwide.

The incident comes at a precarious time for Klobuchar, whose struggle to appeal to black voters dogged her presidential bid.

Hailing from a predominantly white state, she was a relative unknown to black voters in the Democratic primary. As her profile rose, so did hard looks into her record, such as the flawed prosecution of a black teenager, Myon Burrell, for murder. (She has since called for an independent review of the case.)

Klobuchar built a tough-on-crime image as prosecutor in Hennepin County from 1999 to 2007, but police accountability advocates say that tenure has fostered the discontent that exploded into the uprising this week in Minneapolis.

“As far as I’m concerned, she’s a racist [who] basically made our prisons the blackest place in this state,” said Michelle Gross, president of Communities United Against Police Brutality, a longtime activist group that has collected records on police deaths in the Twin Cities area over the last two decades. “She turned nonviolent drug offenses into major felonies. She locked up all of these black men in prisons really to fit her agenda.”

Klobuchar has said that she supervised 10,000 to 15,000 cases a year as Hennepin County attorney, “and I cannot account for everything that happened in every case,” she told the Los Angeles Times editorial board in an interview earlier this year. “I do know that the African American incarceration rate, if you look at the pure numbers, went down 12% since I got there.”

In the 1990s and 2000s, when she came to political power, mainstream expectations were different for so-called law-and-order Democrats. Many Democratic prosecutors used their records to successfully run for higher office, as Klobuchar did in winning a U.S. Senate seat in 2006.

But that political atmosphere changed in the 2010s, when dropping crime rates and an uprising in Ferguson, Mo., over the police killing of an unarmed 18-year-old black man unleashed a national reckoning over the impact of tough policing and the mass incarceration on black Americans.

Suddenly, former Democratic prosecutors such as Klobuchar and California Sen. Kamala Harris found their records coming under fresh scrutiny as they sought the presidency.

Rashad Robinson, executive director of the racial justice group Color of Change, said Klobuchar, unlike Harris, did not make herself available to activists and reporters to explain her record.

“This has not been a priority for her,” Robinson said.

According to records compiled by the Minneapolis Star-Tribune, 30 people died after encounters with the police under Klobuchar’s watch; her office did not charge any of the police involved in the incidents.

That included Officer Derek Chauvin, who is at the center of this week’s protests in Minneapolis for kneeling on Floyd’s neck and who had been involved, with five other officers, in the fatal shooting in 2006 of Wayne Reyes, who allegedly pulled a shotgun on the officers after a stabbing, according to records collected by Communities United Against Police Brutality.

Records from Minneapolis police internal affairs show that Chauvin had been subject to at least 17 complaints over his 19-year career, though only one of them was sustained after investigation. He was charged with third-degree murder and manslaughter for Floyd’s death on Friday.

The 2006 shooting of Reyes happened during Klobuchar’s tenure, just days before she was elected to the U.S. Senate. It was not until 2007, after she moved on to the Senate, that a grand jury decided not to press charges against the officers.

Klobuchar denied that she declined to prosecute Chauvin, calling such claims “a lie.” A spokesperson for the Hennepin County attorney’s office said Klobuchar had “no involvement” in the prosecution of that case.

But Klobuchar acknowledged larger concerns about her policy as a prosecutor to refer every police shooting to a grand jury. The once-common practice has been reconsidered by criminal justice reformers, who see it as a way for prosecutors to avoid accountability. She now says prosecutors should take responsibility to make charging decisions themselves.

Any association between Klobuchar and Chauvin is radioactive, said Cornell Belcher, a Democratic pollster who worked with President Obama, recalling the political maxim: “If you’re explaining, you’re losing.”

Joe Biden has a testy exchange with a prominent black radio personality over the Democrat’s support among black voters and his running-mate decision.

As Democrats debate potential running mates, many insist Biden must find a way to energize voters of color, especially young African American men, who did not vote for Hillary Clinton in 2016 after voting for President Obama four years earlier.

“Folks who decided to sit out 2016, the people who decided to vote third party in 2016, the people who voted in the primary and just didn’t vote for Joe Biden or Amy Klobuchar — all of those sets of voters are going to be important to pull back in,” said Adrianne Shropshire, executive director of BlackPAC, a political group focused on mobilizing African Americans. “Those also happen to be the very voters that are out in the streets protesting what just happened.”

Klobuchar supporters say she brings her own strengths to the ticket, such as her appeal in the pivotal Midwestern states of Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota. Ed Rendell, the former governor of Pennsylvania, said that while Klobuchar had her drawbacks, so did all the other prospects for the job.

“Is Amy Klobuchar the first choice of most African American voters? Probably not. Will that stop them from voting for Joe Biden against Donald Trump? Definitely not,” he said.

Even though the unrest in Minneapolis has brought Klobuchar’s strains with black voters back to the forefront, some activists said it could provide the moment to reframe that relationship.

“This could be a chance for her to be proactive about where she wants to take us,” Robinson said. “But at the end of the day, it would have been much better to do this not under the specter of a job interview.”

Times staff writer Janet Hook in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.