Coronavirus Today: A back door to vaccinate younger children

- Share via

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Friday, Aug. 27. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

There’s a tradition that when a medicine is approved by the Food and Drug Administration, doctors can prescribe it not only for its intended purpose — the one indicated on the label — but for just about any reason a physician thinks would be helpful.

This happens all the time. For instance, it’s not uncommon for a chemotherapy drug approved to treat one type of cancer to be used for another, especially when patients have run out of other options.

Sometimes a drug produces an unintentional but valuable side effect. This is why the diabetes drug metformin is often prescribed for weight loss. It’s also why the blood pressure medication minoxidil, which happens to stimulate hair growth, took off as a treatment for baldness. (It’s now better known as Rogaine.)

These “off-label” uses are so routine that the FDA has a page on its website to assure Americans that the practice is above-board.

Now that the COVID-19 vaccine developed by Pfizer and BioNTech has received full FDA approval for people 16 and older, some parents are hoping it can be used off-label to immunize children who are too young to get it through official channels.

Adolescents as young as 12 are eligible to get the vaccine — now called Comirnaty — through the emergency use authorization issued in May. But that authorization doesn’t extend to those who are 11 years, 11 months and 29 days old. And why stop there? There are plenty of 11-year-olds (and 10-year-olds) who are the same size as (or bigger than) 12-year-olds.

Pedro Brugarolas, a chemist who lives in Boston, told my colleague Amina Khan that he would ask his pediatrician about getting Comirnaty for his son, who is only 2½. Considering how fast the Delta variant is spreading, he said, “anyone who’s not vaccinated is likely to catch it sooner or later.”

Officials at the FDA anticipated such requests, and they were quick to discourage this type of thinking. Dr. Janet Woodcock, the agency’s acting commissioner, said at a post-approval briefing Monday that “it would not be appropriate” to give this vaccine to children under 12.

The American Academy of Pediatrics weighed in as well. While acknowledging that it is now “legally permissible for physicians to administer the vaccine off-label for children aged 11 and younger,” the organization said it “strongly discourages that practice.”

Here’s why it’s dicey: The dosage currently available was selected with adults in mind, and while it also works in kids ages 12 to 15, there’s uncertainty about younger children.

Pfizer and BioNTech is testing its vaccine in volunteers as young as 6 months. That series of clinical trials began in March, and if all goes well, the companies plan to seek emergency use authorization for 5- to 11-year-olds in September or October. A version for infants and toddlers could follow “soon after,” the companies say.

Until data from those trials come in, doctors would have little to go on if they were to offer the vaccine to younger patients.

It’s not simply a matter of adjusting the dose based on body weight, said Dr. Lauren Crosby, a pediatrician in Beverly Hills.

“Little kids are not little adults,” she said. “Their lung size is different, their heart rate is different … [their] metabolisms are totally different. The liver breaks things down differently, the kidneys run through your blood quicker because your heart rate is quicker, and they filter things faster.”

Crosby said requests for off-label vaccinations started coming in just hours after the FDA granted full approval to Comirnaty. With the Delta variant fueling a fourth wave of infections just as kids are returning to school, the queries are understandable. But they’re also premature said Dr. Sean O’Leary, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital Colorado.

“I absolutely get where the concern comes from,” he said. Unfortunately, he added, “we don’t really have any data on the vaccine’s use in that age group.”

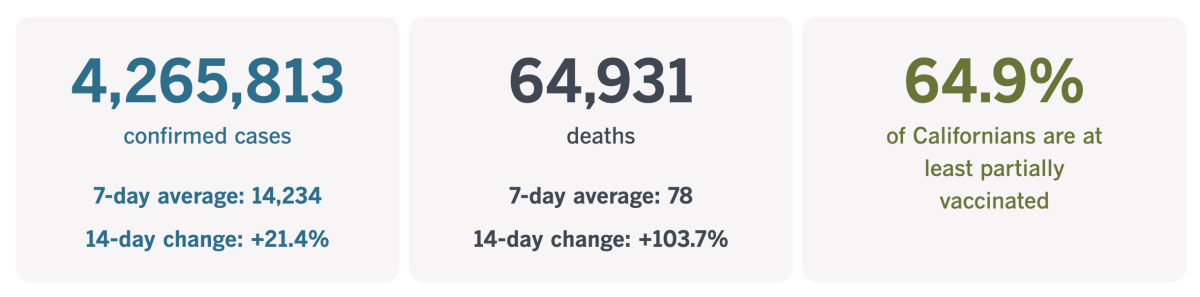

By the numbers

California cases, deaths and vaccinations as of 5:35 p.m. Friday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

How public civility is becoming another COVID-19 casualty

Sometimes the pandemic brings out the best in us — and sometimes it brings out the worst.

The longer the outbreak wears on, the more people lose patience with mask mandates, restrictions on businesses and other rules designed to protect public health. Frustration and exasperation are understandable.

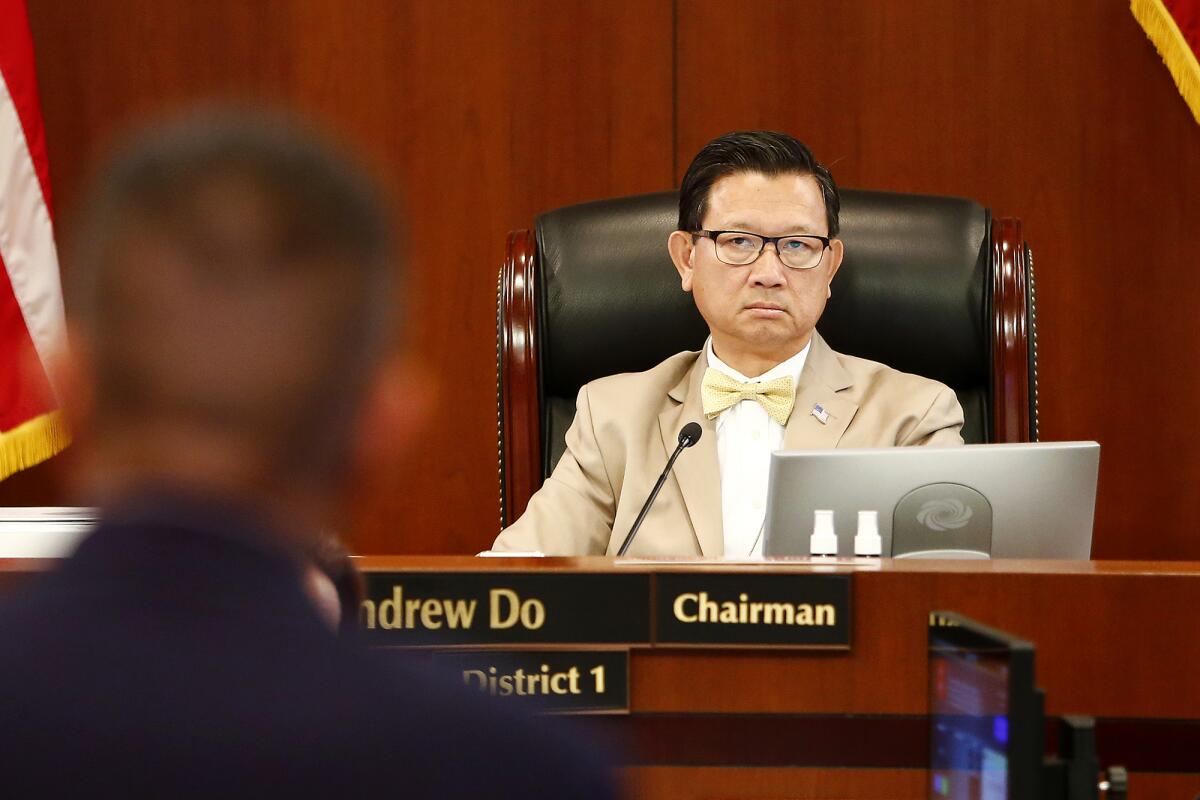

But for a vocal minority in Orange County, those feelings have evolved into anger, resentment — and increasingly, overt racism. It’s been bubbling over at public meetings, especially at gatherings of the Board of Supervisors. Two of the five board members are Asian American, including Chairman Andrew Do.

At a meeting last month, Do touted the fact that 1.2 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine had been administered in the county. Some members of the public responded with hisses and boos. One man in a gray beanie and dark sunglasses shouted at Do, who is Vietnamese American.

“You come to my country, and you act like one of these communist parasites, I ask you to go the f— back to Vietnam,” the man yelled as several others cheered in agreement.

The racist threats aren’t contained to meeting rooms inside the Hall of Administration in Santa Ana, my colleagues Hannah Fry and Anh Do report. Dr. Clayton Chau, the county health officer who is also Vietnamese American, has been forced to contend with protesters outside his Fountain Valley home. On one occasion, they held signs with swastikas, an image of Chau in the guise of Hitler and exhortations to “Go back where you came from.” Another time, they accused Chau of secretly vaccinating children without the consent of their parents.

“I am just an American like everybody else,” Chau said. “For the racists out there, you need to stop it.”

But they’re not listening — and officials aren’t sure what they can do to at least restore public civility (if not actually change people’s minds).

Those who run public meetings have to find a balance between allowing members of the public to exercise their free speech rights and ensuring that other attendees feel safe. Do has threatened to clear the room when crowds become unruly, but he has yet to ask law enforcement officers to remove people who are disruptive.

“We’ve seen hateful rhetoric in the hall of elected officials at so many levels locally here in Orange County. We cannot let this normalize,” said Anti-Defamation League Regional Director Peter Levi. “Every civic and elected leader must call out the hate and do everything in their power to ensure it does not escalate even further.”

The racist sentiments didn’t come out of nowhere, but pandemic fatigue has ratcheted them up and brought them to the fore. And the situation stands to get worse, not better, with the Delta variant pushing the outbreak’s end further into the future.

Protesters regularly gather outside the supervisors’ chambers to demand that Chau be fired. They’re probably encouraged by the fact that his predecessor, Dr. Nichole Quick, resigned last year after defending a countywide mask mandate.

Chau is determined to stay put. The majority of Orange County residents follow the rules and trust science, he said, and he won’t be bullied by an aggressive, misguided minority.

“For my own mental health, I don’t engage with them,” he said. “These are people who are ignorant, meaning they continue to live in their bubble. They don’t step outside. They’re not aware of what’s going on.”

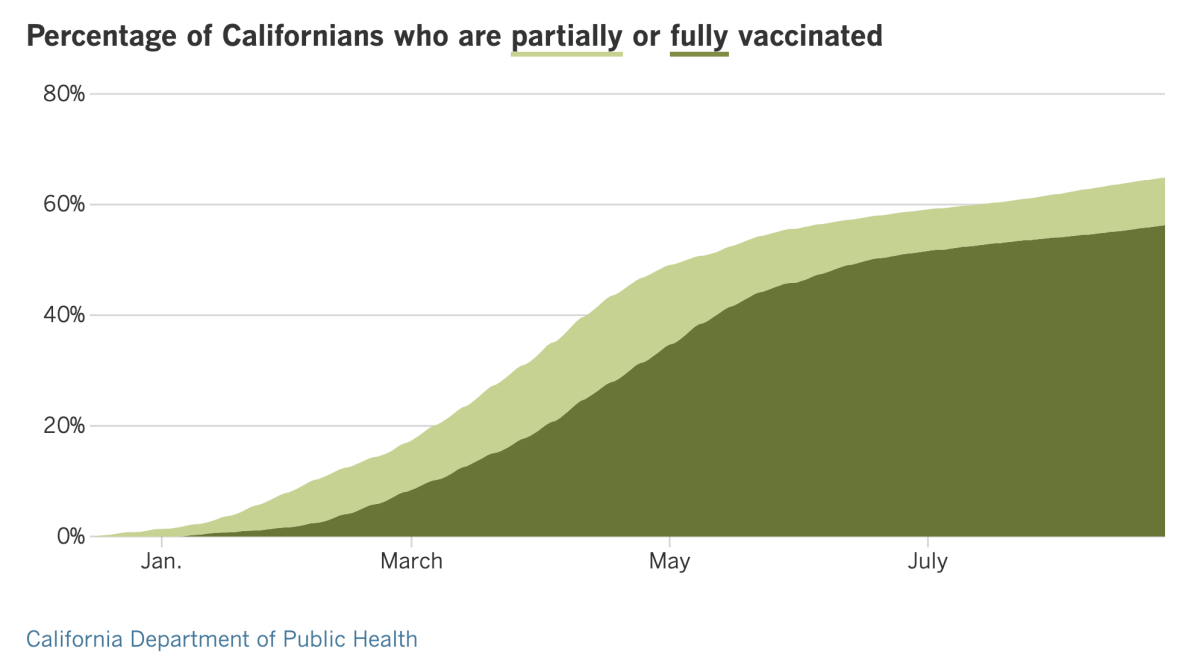

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

In other news ...

A new study of the pandemic’s earliest patients in Wuhan offers a sobering reminder that the health effects of COVID-19 will be with us for a long, long time.

Even a full year after these patients shook off the then-novel coronavirus, survivors were more likely than their uninfected counterparts to be contending with pain, depression and mobility problems. And among those who became sick enough to require hospital care, nearly half reported at least one lingering symptom of the condition that has come to be called long COVID.

The report, published in the medical journal Lancet, offered both good and bad news for COVID long-haulers. On the plus side, the period from six to 12 months after infection brought health improvements for many patients. However, most former patients who were still struggling at six months were not fully well at the 12-month mark.

“This is not good news,” said David Putrino, a rehabilitation specialist who works with COVID long-haulers at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

Meanwhile, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has published several new reports about outbreaks in California. One of them focused on the ripple effects of a single unvaccinated elementary school teacher who showed up for work despite being visibly sick — and then read aloud to the class without wearing a mask, even though face coverings were required indoors. Sure enough, most of the 12 students who wound up being infected were sitting near the front of the room. Four parents and four siblings of infected students also caught the virus. Another six students became ensnared in the outbreak as well, bringing the total number of cases to 27. No one had to be admitted to a hospital.

The outbreak occurred in May and involved the Delta variant, which at the time accounted for only about 6% of samples tested in the state. (It’s now up to 98%, according to the California Department of Public Health.) The teacher said she initially assumed her stuffy nose and fatigue were due to allergies but later developed a cough, headache and possible fever.

A second report published by the CDC focused on coronavirus infections that occurred in Los Angeles County between May 1 and July 25 and helped explain why unvaccinated people have been so much more vulnerable during the Delta surge.

It’s not just that their immune systems are less prepared to beat back a coronavirus infection before it spirals out of control. Researchers from USC and the L.A. County Department of Public Health examined 1,200 adults and found that those who were unvaccinated were more likely to go to bars and clubs, visit friends and family members and attend gatherings — all activities that help the virus spread — and were less likely to be wearing masks while they did so.

Meanwhile, Angelenos who were vaccinated were more likely to avoid gatherings, cover their faces when in public and resist the urge to shake people’s hands, the report said. Add it all up, and you’ll see that by July 25, people who were unvaccinated accounted for five times as many coronavirus infections and 29 times more COVID-19 hospitalizations as their unvaccinated peers.

L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said Thursday that coronavirus cases are still rising among unvaccinated children and teens, some of whom are too young to be eligible for the shots. A few weeks ago, there were 73 cases per 100,000, she said; now there are 307 cases per 100,000.

(Unvaccinated adults are still more likely to be infected than children. The rate of new infections among unvaccinated adults 50 and older was 399 per 100,000, and among younger adults it was 510 per 100,000.)

Cases among children were expected to rise because “as they get back to school and their other activities, there’s just a lot more contact,” Ferrer said. Even so, she called the data from schools “somewhat sobering.”

Five outbreaks involving 27 students and three staffers were reported between Sunday and Wednesday, and those people exposed 135 others. The previous week, there were three outbreaks involving 25 students and 60 staffers, who exposed 79 people.

And then there were nine outbreaks among high school cheerleading and dance teams that affected 131 students and 100 staff members. The infections occurred between July 30 and Aug. 20 and were associated with indoor camps that lasted two to four days and involved students from multiple schools. Each school was asked to enforce its own mask policy, but many students were mask-free during the cheer and dance activities, Ferrer said.

In San Diego, all 11,000 city employees have been told they have until Nov. 2 to become fully vaccinated as “a condition of continued employment.” The notices didn’t specify what would happen to those who refuse to comply. Employees can apply for a medical or religious exemption, though the details of this process are still being worked out.

State lawmakers are looking to boost vaccinations by requiring Californians to show proof of immunization to enter many indoor business establishments. They may also force workers to get vaccinated or submit to regular testing.

The proposal is still in draft form, and the Democrats behind it are weighing things like how much it would cost to implement and how it would be enforced. There’s also the question of how it might help or hurt Gov. Gavin Newsom’s chances of beating back a possible recall.

“I think that the Legislature doing this takes a little bit of heat off of the governor,” said Robin Swanson, a Democratic political consultant. “But at the end of the day, the buck is always going to stop with the governor’s office.”

And we have an update of sorts on how this whole thing began.

According to an unclassified summary of a report ordered by President Biden, four members of the U.S. intelligence community say — with low confidence — that the coronavirus initially spread to humans directly from an animal. A fifth intelligence agency says — with moderate confidence — that the virus jumped to humans though a series of events linked to a lab.

In other words, we still don’t know. And we probably won’t, because China “continues to hinder the global investigation, resist sharing information and blame other countries, including the United States,” the U.S. Director of National Intelligence said Friday.

However, the intelligence agencies agree that China’s leaders weren’t aware of the SARS-CoV-2 virus before the pandemic got going. They also agree that the coronavirus wasn’t created to serve as a bioweapon.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: If COVID-19 tests are supposed to be free, why did I get charged?

Blame it on America’s often irrational healthcare system.

As Business columnist David Lazarus explains, free coronavirus testing was intended to be a cornerstone of the country’s pandemic response. Two federal laws — the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act — explicitly state that patients don’t need to pay for any test that has been approved by the FDA. Those bills are supposed to be paid by health insurance plans, whether public or private.

But if your test provider sends your sample to a lab that’s not in an insurer’s coverage network, the lab may charge higher fees — and the insurer can pass along some of that cost to the patient.

This loophole is made possible by the fact that our system allows different healthcare providers to put different prices on the same service — and insurers get to decide which providers they’ll reimburse, and how much.

Health policy experts have called attention to the loophole, and a trade group that represents health insurance plans has called on Congress to close it by “setting a reasonable market-based pricing benchmark for tests delivered out of network.” If prices are reasonable, the group says, health plans won’t need to share the cost with patients.

What’s reasonable? A report from the trade group says the average in-network cost of processing a test is $130, and some out-of-network labs are charging nearly $400.

Lazarus offers another solution: Do away with coverage networks altogether.

In the meantime, if you’re hit with a testing fee, the onus is on you to deal with it. If you “raise a stink with your insurer,” as Lazarus suggests, it might waive the charges since you weren’t the one who sent your test to an out-of-network lab.

If the insurer isn’t sympathetic, you can file a complaint with the California Department of Insurance.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

Kids in Southern California are settling into their back-to-school routines. For LAUSD students, that includes weekly coronavirus tests.

In the photo above, 15-year-old twins Aniyah, left, and Amiyah Kelly swab their nostrils to gather specimens to test. Younger students, like first-grader Alyssa Ponce, below, have their noses swabbed for them. It’s not exactly fun, but it’s far more comfortable than the brain-tickle test from the pandemic’s early days.

The school district’s $350-million program is the most ambitious of its kind in the country, involving 500,000 tests each week, 1,000 healthcare technicians, 30 lab workers and two daily flights to a facility in Northern California. Public health experts say it will serve as a case study on whether coronavirus transmission can be controlled when hundreds of thousands of students mix with more than 24,000 teachers and nearly 50,000 other staffers on 1,424 campuses across 710 square miles.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Sign up for email updates, and make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Need more vaccine help? Talk to your healthcare provider. Call the state’s COVID-19 hotline at (833) 422-4255. And consult our county-by-county guides to getting vaccinated.

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.