The lowly appendix may play a surprising role in the development of Parkinson’s disease

- Share via

The appendix has long been dismissed as an organ that has outlived its usefulness in human evolution. But new research suggests it may play an active — and detrimental — role in the development of Parkinson’s disease.

In a finding that extends the link between gut and brain health in a surprising new direction, scientists found that people who had their appendix removed were 20% less likely to develop the neurodegenerative disorder than people who did not have appendectomies.

What’s more, surgical removal of the appendix seemed to forestall the appearance of Parkinson’s symptoms, which include tremors, movement difficulties and signs of dementia. Among older patients in whom Parkinson’s disease was eventually diagnosed, those who’d had their appendix removed experienced their first symptoms 3.6 years later, on average, than people who retained the tiny organ.

The authors of the new study, published Wednesday in the journal Science Translational Medicine, stressed that their findings do not make the case for appendectomies as a strategy to prevent Parkinson’s.

Rather, they said, the study offers new evidence for an idea that is gathering support among scientists exploring the origins of Parkinson’s disease: that at least in some cases, the proteins that accumulate in the brain and shut down production of dopamine are hatched in the gastrointestinal tract, possibly by the immune system.

From there, scientists suspect those proteins — called alpha-synuclein — migrate north along the vagus nerve, one of the longest nerves in the body. In Parkinson’s, these proteins somehow get “misfolded” and contribute to the formation of clumps called Lewy bodies, which invade and damage a site in the brain that helps regulate movement.

Although far from definitive, this emerging picture of Parkinson’s disease has begun to focus scientists on ways they might detect and even treat it years before it harms the brain. Gastrointestinal symptoms such as chronic constipation are often evident in people years before they are diagnosed with Parkinson’s — a fact that has fostered interest in the brain-gut connection in the disease, and in the possibilities of earlier detection .

But there are still many mysteries to unravel. Scientists must nail down the full cast of characters — including genes, environmental toxins and misfolded proteins — implicated in the initiation and progression of the disease. They must discern where and how the disease process begins. And they must understand the exact sequence of events by which these multiple contributors interact to do damage.

The new findings suggest the appendix should be a special place of interest in this hunt.

“It’s a piece to the puzzle,” said Dr. Rachel Dolhun, a neurologist and vice president for medical communications at the Michael J. Fox Foundation, a major funder of Parkinson’s disease research. “It suggests protein misfolding that might happen in peripheral organs to be an initiating factor in the disease, and that the appendix might be an organ that could contribute.”

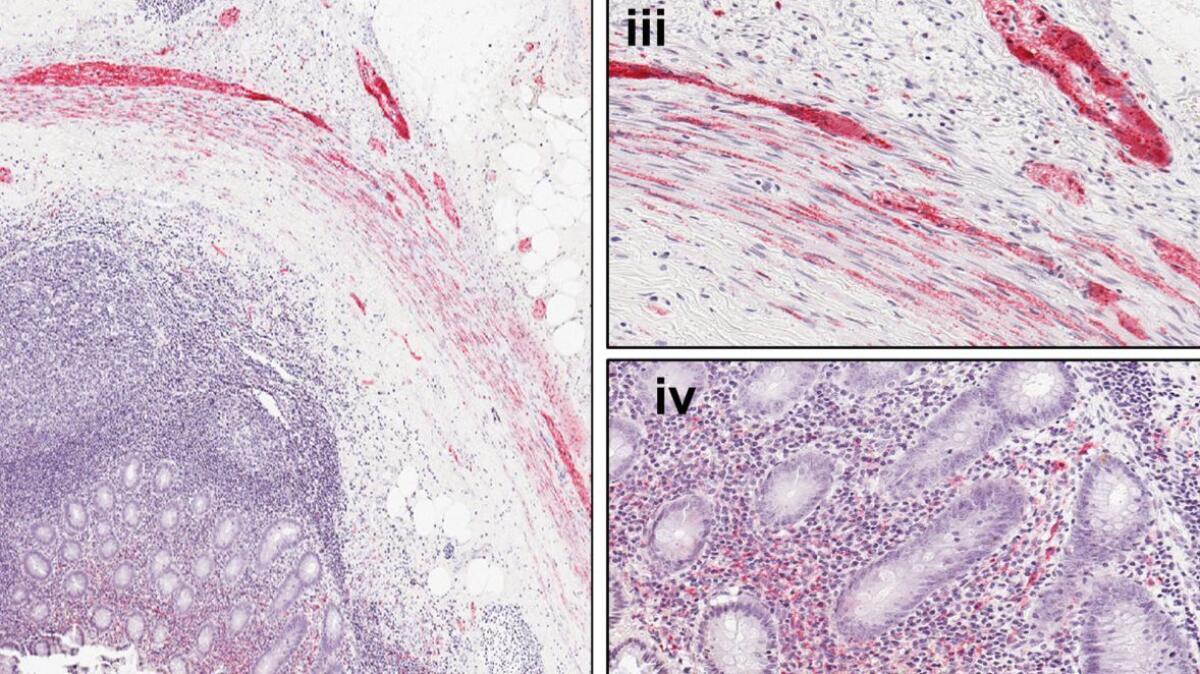

Scientists first observed two decades ago that abnormal alpha-synuclein proteins were evident in the brains of people with Parkinson’s disease, as a component of Lewy bodies. More recently, they have discovered that, in their normal form, these alpha-synuclein proteins were widespread in the guts of healthy younger people.

Suspicions have increasingly fallen upon the appendix as a nursing ground for the potentially troublesome proteins. A thumblike protuberance from the large intestine, the appendix is a common site of acute inflammation, causing pain and inflammation throughout the gut. Surgeons routinely remove it when it flares.

But as scientists have studied the digestive tract’s diverse ecosystem of microbes, they have gained an increasing appreciation for the role of the appendix in regulating immune responses in the gut — with repercussions throughout the body. If alpha-synuclein is created there, or if the appendix spawns the misfolded proteins that are the hallmark of Parkinson’s disease, the presence or absence of an appendix should make a difference in a person’s likelihood of developing that disease, the authors of the new study reasoned.

It was a hypothesis they could test, if they were able to scour the comprehensive medical records of a huge population over many decades. In Sweden, a country with meticulous record-keeping and a national registry of patients followed from cradle to grave, they had two options.

One was a database that contained detailed medical records for 1.6 million Swedes over an average of 54 years. Many of them had appendectomies; far fewer of them were diagnosed with Parkinson’s.

The analysis revealed that removing the appendix early in life was associated with a roughly 20% reduced risk of developing Parkinson’s disease.

The effect was magnified in people who lived in rural areas. Environmental contaminants have been found to drive up Parkinson’s risk, and greater exposure to pesticides in rural areas is widely thought to explain the greater prevalence of the disease there. In that population, appendectomies were associated with a 25% lower risk of Parkinson’s.

When the researchers considered the timing of an appendectomy, they found further evidence to suggest a central role for the appendix in Parkinson’s disease.

The decline in Parkinson’s risk was apparent only when the appendix (and the alpha-synuclein proteins contained within it) were removed early in life. Removal of the appendix after the disease process starts, however, had no effect on disease progression, they found.

The study authors also analyzed appendix tissue samples obtained from 48 people who had undergone routine appendectomies and were not diagnosed with Parkinson’s later in life. They found that 46 of the samples contained high levels of alpha-synuclein clumps similar to those seen in Lewy bodies, and that the age of the person from whom they were excised did not seem to matter. In a disease linked to advanced age, this was a surprise.

In the lab, the researchers found that this excised tissue from healthy individuals could easily be made to form the dangerous clumps seen in the brains of people with Parkinson’s.

All of this suggests a model in which rogue species of alpha-synuclein might jump-start the formation of misfolded protein clumps inside the appendix, the authors wrote.

But that doesn’t mean the riddle of Parkinson’s disease, first described in 1817 by Dr. James Parkinson, is close to being solved. (Coincidentally, Parkinson was the first to describe acute appendicitis, in 1812.)

“There could be many origins” of the disease, said coauthor Viviane Labrie, a neurogeneticist at the Van Andel Research Institute in Grand Rapids, Mich. The removal of the appendix “seems to be associated with a 20% reduction in that risk.” But while that is a robust finding, she said, it leaves much to be explained.

“This work is nicely done, and there is a lot of power in the size of the population these authors used,” said Anumantha Kanthasamy, a Parkinson’s researcher at Iowa State University in Ames who was not involved in the new research.

Kanthasamy stressed that the association found in the study does not necessarily suggest that removal of the appendix directly lowered Swedes’ risk of Parkinson’s. The relationship could well be more complex: For instance, the appendicitis attack that led to the organ’s removal might ultimately be found to be the key to a person’s protection.

“It adds to the concept that, in Parkinson’s disease, changes that take place in the peripheral nervous system, including the gut, probably occur much earlier than what you see as the classical pathology in the brain,” he added. “And it adds to our understanding that the gut and the peripheral nervous system are intimately connected to the brain.”

MORE IN SCIENCE