First person: Carl Erskine remembers Jackie Robinson as a man who ‘stood his ground’

- Share via

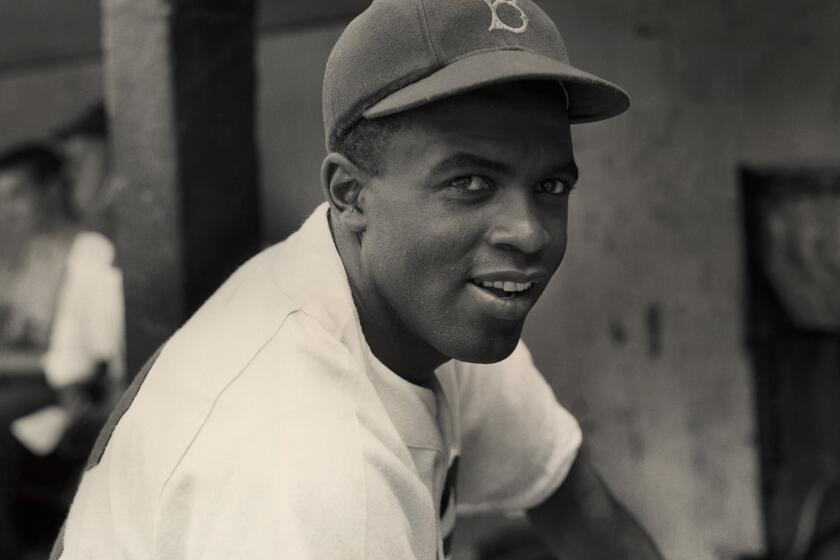

Jackie Robinson made his major league debut 75 years ago Friday. He died 50 years ago, and few fans alive today can say they saw Robinson play.

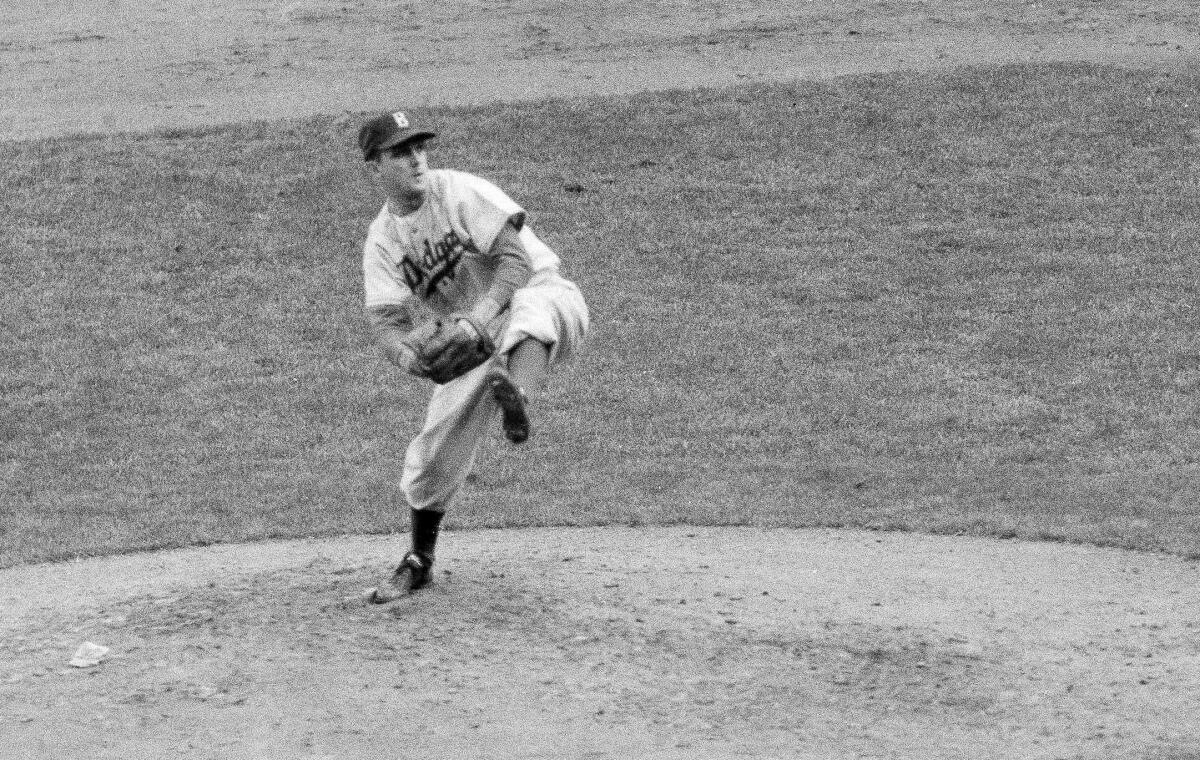

Carl Erskine saw him play every day. Robinson made his debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947, Erskine followed in 1948, and the two remained teammates until Robinson retired after the 1956 season. When the Dodgers moved west in 1958, Erskine was the starting — and winning — pitcher in the team’s first game in Los Angeles.

Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey had warned Robinson he would have to turn the other cheek at every turn if he were to succeed at breaking baseball’s color barrier and proving a Black man could endure in the major leagues. Robinson turned endurance into excellence, and ultimately into a place in the Hall of Fame.

Seventy-five years ago Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier. Fifty years ago he returned to Dodger Stadium, a thaw in a frosty relationship.

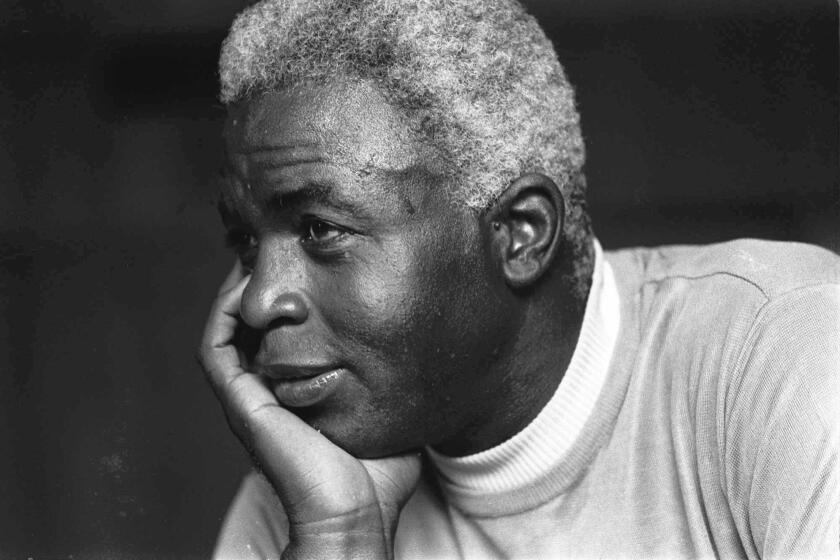

Erskine shared a clubhouse with Robinson then and shares his memories with Los Angeles Times readers now. Erskine, 95, spoke with Times baseball columnist Bill Shaikin from his home in Anderson, Ind.

First up: the first time he met Robinson.

I was in the minor leagues at the time. The big club, the real Dodgers, came through to play us in an exhibition game. After the game was over, Jackie came over to our side of the field and said, ‘Where’s Erskine?’ I went out and shook hands with Jackie. I had never met him before. He said, ‘Young man, you’re not going to be in the minor leagues very long with the way you throw.’ That was a big boost for me. Sure enough, by midseason, I had won 15 games, and they called me up to the Dodgers.

I joined them in Pittsburgh, and the first guy to my locker was Jackie. He said, ‘I told you you couldn’t miss.’ We struck up a good friendship.

In Brooklyn, I came out of the clubhouse one day, and there was an area where wives and family members could wait. When I came out of the clubhouse, Rachel and little Jackie (Robinson’s son) were there. I just walked over, the natural thing to do, and talked with them for a few minutes. The next day, Jackie said he wanted to thank me for what I did. I said, ‘I didn’t pitch yesterday.’ He said, ‘No, you walked over to talk, out in front of the crowd, to talk with Jackie and Rachel.’ I was almost embarrassed. I said, ‘Jackie, don’t thank me for that. Shake my hand for a well-pitched game.’ That was a natural thing for me to do. But he was impressed by that.

I had a lot of good buddies growing up, Black kids in my neighborhood, and I never had any problem at all with that. Jackie asked me one day, ‘How come you don’t have any problem with this black and white thing?’ I said, ‘My best friend growing up, from 10 years old on, was Johnny Wilson, a Black young man in my neighborhood. So that never was an issue with me, and it never will be.’ (Wilson grew up to play for the Harlem Globetrotters.)

There were some early experiences where the hotels would say, ‘We don’t serve Black guests.’ In one instance, Mr. Rickey said, ‘Can he stay in my room with me?’ And that’s how they got by. Once Jackie got established in the league, most of that stuff went away.

In baseball, a lot of nasty stuff comes out of the other dugout. And, when you’re on the road, from the fans in the stands.

Jackie took a lot of heat, but he handled it very well. I knew Robin Roberts of the Phillies. I had pitched against him many times, and I got to be good friends with him off the field. He said, ‘I told our team, we’ve been getting on Jackie, and it’s killing us. Let’s get off him, because the more we get on him, the more he beats us.’ That was the way Jackie was. All the heat that he took just energized him. He took it out on the bases.

He had a dignity about him. As tough as he was, and as fierce a player as he was, he had to make a promise to Mr. Rickey that he would never fight. I never saw Jackie fight in the clubhouse, on the field, in a restaurant, any place. He promised Mr. Rickey he would never fight and, to my knowledge, history can record that he never did. He was true to his word.

All of us on the team watched how Jackie handled himself, in some very tight spots sometimes. He was very intelligent, very well spoken. He handled it. He took the edge off it. And then people began to realize, this guy is a class person, and he’s a great player. Any resentment kind of faded away after they got to know Jackie and watch him play.

I never saw Jackie backhand a ball. He always was able to get in front of the ball, even on a ball up the middle, playing second base. The ball would be hit to his right, and he would always be able to get in front of the ball and make the play.

Jackie was so quick with his hands and feet. That’s why he was a terrific baserunner. He was quick, and you’ve got to separate that from being fast.

He saved my no-hitter. He made a play at third base, a ball hit by Willie Mays, that was to the left of him at third base. It would have been a base hit with almost anybody there, but Jackie was so quick, and he stabbed that ball. It was hit quite a ways to his left, and he turned it into an easy out.

Our nation was truly black and white. That’s the way it was. It was a very distinct cultural divide. So with what Jackie did, people saw what a gentleman he was, and how intelligent he was, and how exciting he was as a player. He broke down lots of social barriers that were ingrained in our society for a couple of centuries.

In 1972, 25 years after he broke MLB’s color barrier, Robinson reflected on the ongoing fight for equality. Former Times sportswriter Ron Rapoport recounts that interview just months before Robinson’s death.

He didn’t push hard, but he stood his ground. He handled the press very well. He was a thinker. So he was aware he was having quite an impact on the game of baseball, not only as a player but as a Black individual.

I think Jackie would have been really pleased that a Black player became a manager. I think he’d say this is a good start, but there’s plenty of room left for advancement.

I admired Jackie. He didn’t have to shy away from anybody. He handled himself so well, with the press and with the fans. He was truly a Hall of Famer.

I always thought it was interesting that, when Jackie went into the Hall of Fame, it was very symbolic. The Hall of Fame plaques are all the same color. They’re all bronze. That’s a symbolic message from the Hall of Fame.

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.