Must Reads: An Irish team was cursed by a priest. One of its living champions hopes to see the losing streak end

- Share via

On the table sits a notebook; in it a list of villages, towns and cities, each with a notation.

At every stop, whether in Ireland or the United States, it lists a trophy or medal he won. Between them, universities and hospitals — early steps in a medical career that lasted more than 60 years and took him from the Irish village of Swinford to Long Beach.

Padraig Carney has prepared for this interview. If the notebook wasn’t evidence enough, it’s clear from what he’s wearing.

The jersey is newer and much lighter than the thick cotton version he wore in the 1950s, and it’s without a lace-up collar. There are a few extra decorative touches of red among the green, more work put into the design. The midriff bears the most notable change, the name of a sponsor.

But the main pattern is the same: Green with a thick, solitary, horizontal bar of red. County Mayo’s colors. Just as he wears on the postage stamp that honored his induction into the Gaelic Athletic Assn. Hall of Fame.

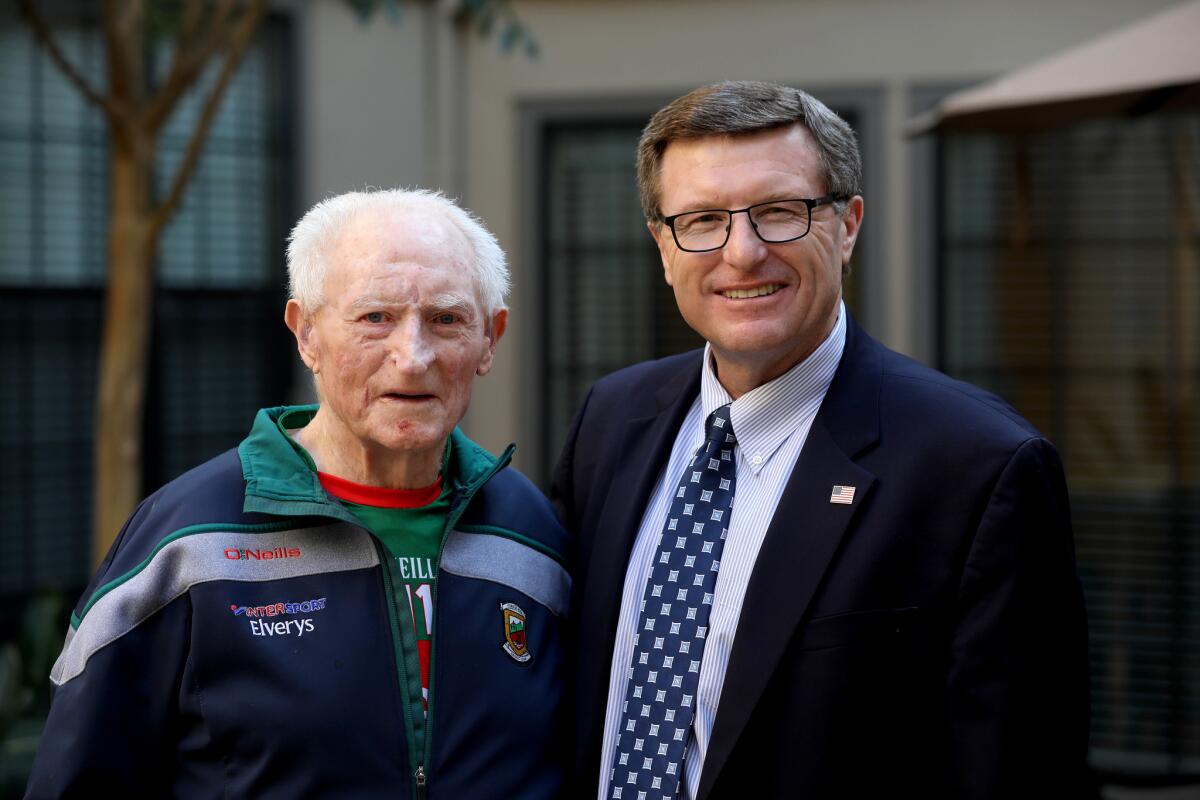

Carney, 90, has welcomed a visitor into his tiny but tidy studio apartment at an assisted living facility in south Orange County. A retired physician, he is the father of four, including son Cormac, a record-setting receiver at UCLA in the early 1980s.

He will talk about his career as an athlete, his time as “the Flying Doctor,” his children and grandchildren. But first he wants to put a legend to rest.

There are people who say the old doctor is cursed.

In 1951, Carney’s county, Mayo, won the All-Ireland Senior Championship in Gaelic Football. That much can be verified.

From there, lore has it that as the team returned from Dublin it stopped in the village of Foxford, where a funeral procession was taking place. The players, still buoyant from victory, were said to have continued to celebrate as the funeral passed.

Which is when the presiding priest declared that Mayo would never win another All-Ireland title while any member of the team was alive.

Since then, the team has played for championships in 1989, 1996, 1997, 2004, 2006, 2012, 2013, 2016 and 2017.

And lost them all.

Carney is one of two living members from that ’51 team; Paddy Prendergast, 92, is the other.

Could the jinx be real?

“I don’t believe in curses,” Carney says.

Each of Mayo’s championship losses seems to have gone one of two ways, instant capitulation or last-second heartbreak. Last year, forward Cillian O’Connor struck the post with a stoppage-time free kick that would have won the game. Instead, Mayo lost in extra time by a single point.

“It wasn’t the curse that cost them those finals, it was just bad decisions,” Carney says, recalling the close calls from last year’s final. “There was O’Connor missing by less than a foot, there was a Mayo player (halfback Lee Keegan) brought down for a penalty but the referee gave a free.

“It might get into the minds of the players sometimes, but a couple of these finals something else was the difference.”

There are other reasons as well that Carney thinks the curse is a farce. He produces an article quoting Gaelic Athletic Assn. historians who found no mention of the curse until decades later, and who said some of Carney’s late teammates denied it happened.

“We didn’t all travel back together, so the story that we all passed a funeral coming back couldn’t be true,” Carney says. “I wasn’t aware of it until much later. I only heard it being said about these recent teams that started getting so close.”

This year, Mayo was upset in the qualifier rounds by Kildare. Still, Carney, who used to travel back to Ireland to watch every final at Croke Park, woke up early on Sunday to watch Dublin win its fourth consecutive title, 2-17 to 1-14 over Tyrone.

There’s a good chance the “Curse of ’51,” isn’t real. The list of honors scrawled in Carney’s notebook — the stuff that made him a legend in Gaelic football — is.

Resembling a cross between soccer and rugby, Gaelic football is Ireland’s most watched sport; the All-Ireland Final, played annually before sellout crowds at 80,000-seat Croke Park and watched by around a quarter of Ireland on television, is its annual pinnacle.

The game’s ties to Irish identity go deep — the rules were codified in 1887 as an alternative to the English codes of football. In 1920, during the Irish War of Independence, the symbolic importance of the game became more clear, as British forces opened fire on Croke Park during a game, killing one player and 13 spectators.

Carney was a prodigious talent from the start. His toughness and skill in a sport so central to the Irish identity may have been tied to the lives of his parents.

His father, Tom, fought in the Irish War of Independence, where he was wounded in an ambush. His mother, Nellie, was a member of Cumann na mBan, a women’s paramilitary group, and spent a year in prison for the association between 1923 and 1924.

After excelling on the field and in the classroom at Culmore National School, Carney made his debut for the Mayo senior team at the age of 17, before he’d made a single appearance for its minor (under-18) team.

He scored with his first kick of the game.

“As soon as I stepped on the field, I felt like I could hold my own out there,” Carney says.

In 1946, he earned his first appearance in the sport’s premier competition, the inter-county championship, where the 32 counties of Ireland — alongside emigrant teams based in London and New York — compete to lift the 19.05-pound, 45-pint silver trophy known as the Sam Maguire Cup.

In 1948, Carney, then 20, played in the All-Ireland Final against Cavan. Mayo was seeking its first title since 1936.

“There’s nothing like being in Croke Park on the day of the All-Ireland Final and walking around that field,” Carney said. “You really feel it, that pride inside you. You’re eager to get out there and tackle that other guy.”

In the final minute, Carney had a chance to tie the game with a free kick, but it was blocked — though Carney says the defender was allowed to encroach on the 14 yards of space kickers are granted.

Two years later, Mayo returned to Croke Park. And this time, it defeated Louth for the title. But for Carney, celebrations would just get in the way of his budding medical career.

“Everyone in Mayo was so excited about it,” Carney said. “We toured to different towns all around the county. But I had to get back to reality very quickly. I had to make a living.”

The next year, Carney and Mayo returned for the game that inspired the legend. Carney led both teams in scoring with six points and earned Man of the Match honors on his way to a second Sam Maguire Cup.

“Padraig Carney made all the difference,” the Western People reported the next day. “This statement was on the mouth of every spectator leaving the field.”

Carney, on first-name terms with the trophy, says: “It’s a great honor to hold Sam and know you’ve won it. Everyone who plays the game wants to win an All-Ireland.”

His medical career took him all around Ireland. He studied at University College Dublin, where he won the inter-college Sigerson Cup three times in four years. Then he worked at the County Hospital in Castlebar, Mayo’s largest town. There, he played for the Castlebar Mitchels and won county championships in 1951 and 1952. Next it was the village of Charlestown, where he won the All-Ireland junior club championship.

Soon, his career sent him to New York, alongside his wife, Moira, also a doctor. But Mayo still came calling. Carney flew back to Ireland to compete in the National League, a secondary inter-county competition.

“I’d fly out of New York on a Friday,” Carney said. “Out of Idlewild. It wasn’t called JFK yet.”

The first part of the trip took 12 hours, a flight that took him to Newfoundland, then to Shannon in the west of Ireland. From there, he caught another flight to Dublin, arriving in time to sleep at his father’s home on Saturday night. “On Sunday, after the game was over,” he says, “I’d go to the airport and fly back and get to work on Monday in the hospital in New York.”

Hence the nickname “The Flying Doctor,” bestowed by radio commentator Michael O’Hehir.

Padraig Carney’s accomplishments as a Gaelic football star never caused more than a ripple of interest in the United States. Around Southern California, where the family moved to stay in 1959, his main connection to the sports landscape was as Cormac’s father.

Cormac never played Gaelic football; he played the much different sport of American football. A wide receiver, he led UCLA in receiving yards in 1980, 1981 and a Rose Bowl-winning 1982 season. He earned All-Pac-10 honors as a junior and senior and finished his career with the Bruins as the program’s career leader in receptions and receiving yards.

“I remember one game against Wisconsin,” Padraig Carney says. “He caught a pass and then took a big hit. He didn’t move for a little while, but he wasn’t badly injured and he held onto the ball. I was concerned about his safety when he played much more than I was concerned with my own when I was playing.”

After a brief stint in the USFL, Cormac graduated from Harvard Law School in 1987. In 2001, he was named to the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California, where in 2014 he would rule that the death penalty in California was unconstitutional.

Cormac was not the only Carney child to have success on and off the field. Brian, the eldest, played linebacker for Air Force before becoming an orthopedist at Dartmouth. Terrance played guard for the University of the Pacific and is a lawyer in Orange County. The youngest, daughter Sheila, is a librarian at Johns Hopkins University.

The sporting gene was passed on to a third generation of Carneys, too, including Jake, a former Notre Dame defensive back, and Katie, a former soccer midfielder for Nevada Las Vegas.

The family patriarch, they probably know, was quite the showman in his day.

The ball would go left and right as Padraig Carney worked his way past his man. Then, into the air, where it remained stationary at the end of his arm. As if to prove that he had advanced beyond the defender with the ball still in his possession, he would hold it aloft for all to see before kicking for a score.

His antics were noted by Sean Purcell of neighboring County Galway, who once described his great rival as a “character” with “a little bit of arrogance, but the skill to match.”

Carney recalls that his flashy style was on full display in the ’51 final. “I was having one of my best games,” he says, “and when I was playing well I liked to entertain too.”

Carney chuckled when presented with accusations of showboating.

“You have to go after it,” he says.

Then again, if he really wanted attention above all else, he probably wouldn’t let the truth get in the way of the “Curse of ’51.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.