Flagstaff finds new life in Old West heritage

- Share via

This town used to bill itself as “The City of Seven Wonders” — a reference to the Grand Canyon and other nearby Northern Arizona attractions. The catch? Not one of the wonders was actually in Flagstaff.

Nowadays, the official slogan is more local and less grandiose: “They don’t make towns like this anymore.”

I lived in Flagstaff until age 5 and have passed through a few times since, but my vague memories of the downtown district were not especially glowing. A row of seedy bars and curio shops lined Route 66, just north of the railroad tracks. Northern Arizona University dominated the south side, but the campus was invisible from the main drag.

I was intrigued by rumors of a resuscitated downtown. The city’s first public plaza, Heritage Square, opened in 1999. The surrounding town center reportedly was hopping with new restaurants and shops. So I decided to see how Flagstaff fared without leaning on its more famous outlying wonders.

My octogenarian mother, who lives near Phoenix, also wanted to revisit her former haunts — but Flagstaff would be too cold for us during much of the year. Located a few miles south of the 12,000-foot, snowcapped San Francisco Peaks, Flagstaff is just shy of 7,000 feet in elevation, which makes for generally wonderful summer weather. As we escaped Phoenix, the temperature was on its way to 104. After driving north for nearly three hours — slowed slightly by fellow travelers presumably escaping the heat — we found it an agreeable 78.

Flagstaff is surrounded by the Coconino National Forest, part of the largest stand of ponderosa pines in the country. We ate a light lunch at Jackson’s, a contemporary American restaurant a few miles south of town with windows that provide forest and meadow views. Then we entered the city limits.

The community was born around 1880 near a spring that still runs today in a tiny park on the west side of Flagstaff. The original buildings are long gone; the spot is marked only by a plaque and playground equipment.

We drove by the park with Alan Lew, a professor who specializes in the geography of tourism and recreation at Northern Arizona University, whom we met through a family friend. Five minutes later, we arrived at a lookout point atop Mars Hill, slightly farther west. From our perch about 200 feet above the streets, we looked down at a city that has grown from fewer than 10,000 residents when I lived here in the ‘50s to nearly 60,000.

We could easily see the railroad track that has bisected Flagstaff from the beginning. The first depot — actually just a boxcar — was stationed on flatter ground in 1882 east of that first settlement. By 1884, local businesses had abandoned the spring to relocate next to the boxcar, and that spot became the center of downtown Flagstaff. The logging and ranching economy grew up around the rails.

By the 1980s, Lew said, downtown was dead. Much of the retail had been lured by a new type of boxcar: a shopping mall on the eastern outskirts.

At the heart of things

The centerpiece of Flagstaff’s revitalized urban core is Heritage Square, a brick plaza with architectural details that represent local history and geology, such as a wooden flagpole with a base made of Grand Canyon rocks arranged chronologically.It’s often abuzz with activity. On our Friday afternoon, it was swarming with families, toddlers bouncing to the beat of a live band covering “I Shot the Sheriff.” A few hours later, the place was even busier, although quieter. Free movies are projected outdoors on Friday nights during the summer, and several hundred people with picnic hampers were taking in “The Incredibles.” The next afternoon, a troupe of Middle Eastern dancers and musicians defied threatening clouds and occasional showers.

Surrounding Heritage Square are several blocks of shops, restaurants and bars — although the bars are now young-adult hangouts instead of the dives that used to line these streets. We ate well at Pasto, a Mediterranean restaurant across the street from Heritage Square, with intensely colored interior walls and a back patio that provided a retreat from the hubbub of the square.

Examining the nearby shop windows, my mother and I noticed that not one of the shops was selling curios; they appear to have been replaced by stores selling Native American crafts.

But the most distinctive feature of downtown Flagstaff’s gentrification is the dearth of chain stores. Local retailers rule their own retail roost.

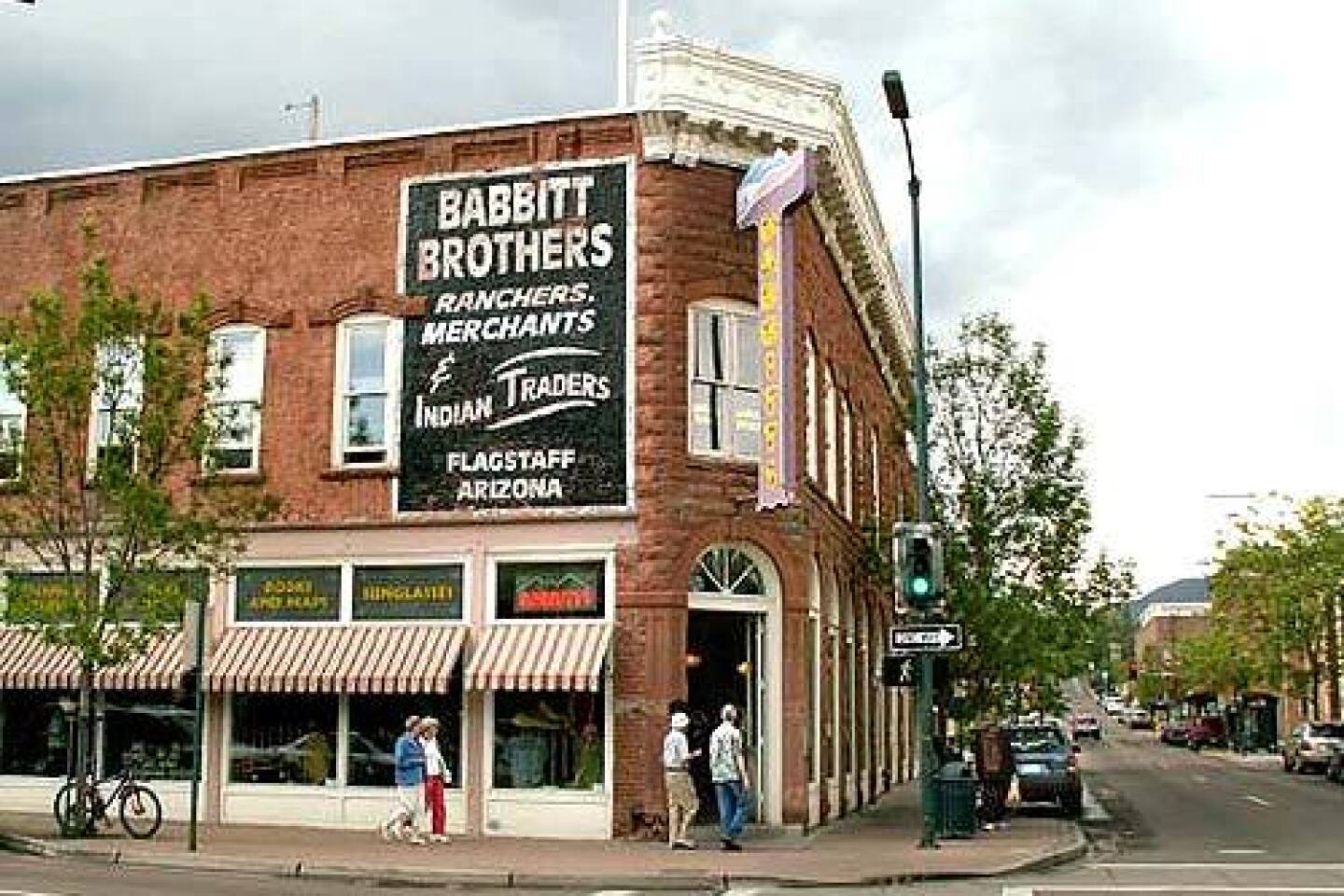

Exhibit A: Babbitt’s. Once the biggest department store in town, it withered in the face of mall competition. (It was founded in 1889 by five brothers, the same family that later produced Bruce Babbitt, former Arizona governor and U.S. secretary of the Interior.) But several Babbitt’s boutiques survive; the former headquarters is now a mountaineering shop. The exterior was restored to its original red sandstone after the removal of a modernistic white facade tacked on in the late ‘50s.

Our lodgings also respected Flagstaff’s history. We stayed in a Western-style suite at the Inn at 410, a bed-and-breakfast in a Craftsman-style house a few blocks from the downtown bustle. It’s impeccably maintained and serves elegant breakfasts in the parlor or in a garden gazebo.

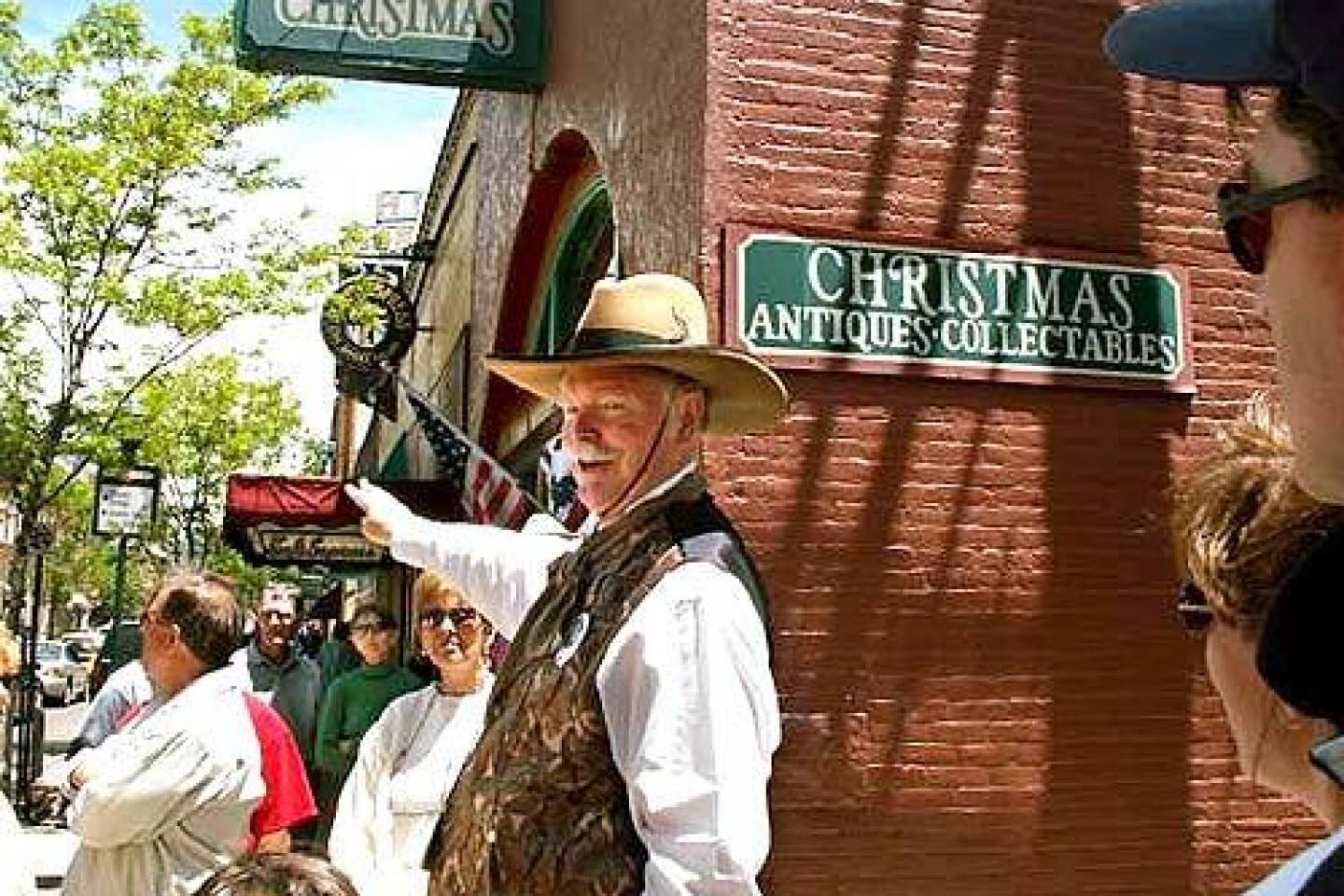

On alternate Sunday mornings during the summer, Richard and Sherry Mangum, wearing elaborate period-style outfits, conduct strolling tours of downtown. He’s a Flagstaff native who retired after 17 years as a Superior Court judge; she’s lived here since childhood.

They split us into two groups departing from the railroad depot; we followed the former judge. (He’s a well-known local fixture; one man who saw our group coming barked, “Here comes da judge! Here comes da judge!”) Towering over most of his listeners, Mangum delivered anecdotes about Flagstaff’s wilder days with a laconic style and a twinkle in his eye.

Sights on the outskirts

FLAGSTAFF’S charms stretch beyond those few blocks of downtown. We toured the Riordan Mansion, a 13,000-square-foot duplex near the college campus filled with gorgeous Craftsman furnishings. It was constructed in 1904 by two brothers, the town’s logging moguls, and is now a state historic park.More glimpses of local history are on display at the Pioneer Museum, northwest of downtown. It’s in a former hospital for the indigent built in 1908. I laughed out loud over an exhibit about the hospital itself, where payroll records reveal that one of the official job titles was “flunky.”

We couldn’t ignore Flagstaff’s most famous landmark, Lowell Observatory, best known as the place where apprentice astronomer Clyde Tombaugh discovered the planet Pluto in 1930. After dark, visitors stand in line, sometimes for hours, to peer through the 1896 Clark Telescope, located under the observatory’s soaring wooden dome.

A more contemporary portable telescope is set up outside as well. The evening star shows can be curtailed by summertime thunderstorms, but a visitor center built in 1994 offers an array of kid-friendly exhibits.

Astronomy buffs can pass the daylight hours at another attraction — free and not found in the standard guidebooks. The U.S. Geological Survey drafts its lunar and planetary maps in its Flagstaff quarters. The hallways in the USGS Shoemaker Building, northeast of downtown, are covered with colorful maps and photos — some with 3-D glasses provided — of the celestial bodies.

A display in one long corridor illustrates the relative distances in the solar system. At one end are colorful balls representing the sun and the closest planets, including ours; at the other end — far away — is Flagstaff’s own favorite-son planet, Pluto.

They may not eclipse Sunset Crater or the San Francisco Peaks, but Flagstaff has some wonders all its own.

Budget for two

Lodging

Two nights at Inn at 410, with tax $408

Transportation

One round-trip airfare, LAX to Phoenix, rental car $239

Meals

Jackson’s Grill lunch $20

Josephine’s lunch $20

Pasto dinner $54

Other meals $38

Entertainment

Riordan Mansion, Lowell Observatory, Pioneer Museum $24

Total $803

Distance from L.A. 467 miles

WHERE TO STAY:

Inn at 410, 410 N. Leroux; (800) 774-2008, inn410.com. Doubles and suites, $150-$210.

WHERE TO EAT:

Jackson’s Grill, 7055 S. Highway 89A; (928) 213-9332.

Josephine’s, 503 N. Humphreys St.; (928) 779-3400.

Pasto, 19 E. Aspen Ave.; (928) 779-1937.

WHERE TO GO:

Heritage Square, Aspen Avenue east of Leroux Street; (928) 774-6929, heritagesquaretrust.org.

Riordan Mansion State Historic Park, 409 W. Riordan Road; (928) 779-4395, azstateparks.com.

Lowell Observatory, 1400 W. Mars Hill Road; (928) 774-3358, https://www.lowell.edu .

Arizona State Historical Society Pioneer Museum, 2340 N. Fort Valley Road; (928) 774-6272.

Flagstaff Historic Walk, (928) 774-8800. 10 a.m. today and alternate Sundays through Sept. 4. Reservations suggested. Donation only.

USGS, Shoemaker Building, 2255 N. Gemini Drive; (928) 556-7000. Free. Closed weekends.

— Don Shirley

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.