Against the odds, some Syrians rebuild amid the ruins

- Share via

ALEPPO, Syria — Bakri Sino spends his days combing through the rubble of a Scud attack, putting aside reusable blocks of concrete, twisted metal rods and still-intact doors. On one of the few walls left standing, someone has spray-painted, “Now what?”

Dressed in a dusty black T-shirt and matching grimy slacks, he steps over piles of concrete balanced atop the detritus of interrupted lives as if he’s walking on steady ground.

The former metalworker has grown accustomed to crossing these heaps after a month of this labor.

“These rocks, they can all be reused,” Sino says, managing to see something more than a lost cause in the debris. “It can be fixed.”

Owners of the destroyed homes pay Sino $2.50 a day to salvage what he can. They have moved elsewhere temporarily, but all plan to return soon, he says.

A young boy from the neighborhood works by his side.

“They’re all going to rebuild — what else are they going to do?” the boy says.

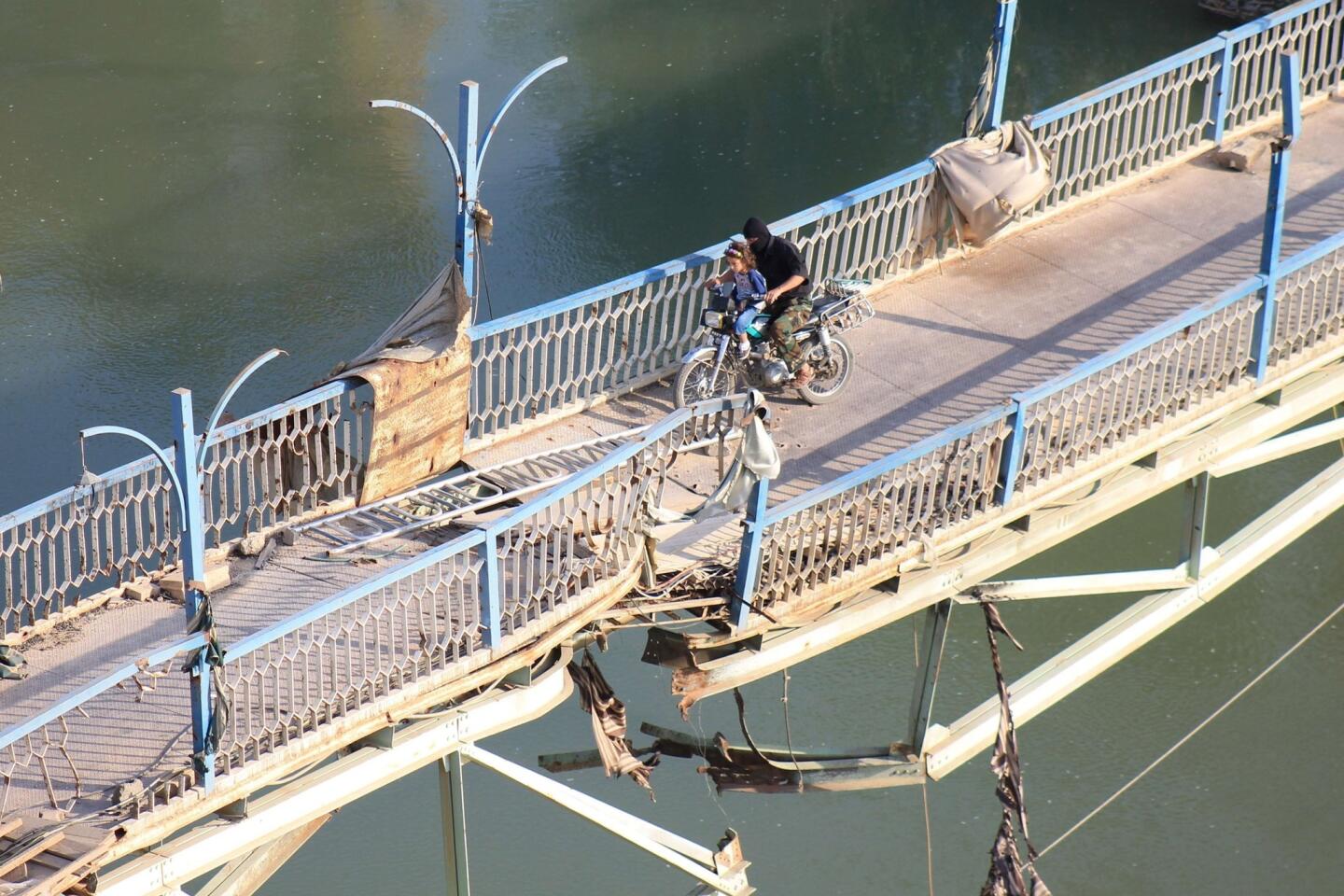

Here in one of Aleppo’s battle-scarred neighborhoods, where urban warfare has been met with heavy artillery, residents teeter between fatalism and faith. Even as surface-to-surface missiles are launched their way and warplanes fly above, they’re building amid the ruins, knowing it may not last.

Many who remain in their homes speak of preserving their dignity; they say they would rather die on their own land than be humiliated in refugee camps or elsewhere abroad.

“The person who is rebuilding his house knows that it can be hit the next day with a shell and destroyed again,” says Abu Ahmad Yassin, an electrician who heads the Islamic Administration for General Services, which restores water and electricity in opposition-held Aleppo.

With his bushy beard and eyebrows, and dressed in a plaid shirt and a yellow hard hat, Yassin looks like an Arab Bob the Builder. Hope dies last, he says.

“They are rebuilding with faith in God and hope in the revolution that soon it could be over.”

**

When the Scud missile struck less than 50 feet from Abdulaziz Haizaan’s home, three generations of his family braced under the force of the attack.

Much of the top floor crumbled, doors blew out, and glass shattered throughout the house.

Around them, homes that had stood next to one another for decades became one massive gray mass of rubble with dozens of his neighbors’ bodies buried underneath. Even in buildings that remained standing, floors lay pancaked atop one another. The neighborhood seemed uninhabitable.

But a week later, the retired factory worker borrowed about $1,150, an amount he doesn’t know how he will repay, and began to rebuild.

“Where are we going to go?” Haizaan said, repeating what has become a bleak anthem for those who have chosen to remain in their homes despite the destruction wrought by government bombardments.

Six neighbors have rebuilt parts of their homes, and others are living in severely damaged houses. Only a few have left.

Across Syria, nearly 2 million people have fled the country and more than 4 million are internally displaced. But many are unwilling to abandon their homes or, more often, feel they are financially unable to.

Additionally, neighboring Jordan, Iraq and Turkey have prevented many refugees from entering in recent months, leaving tens of thousands of Syrians stranded and with few options.

And so, under the barrage of forces loyal to President Bashar Assad, the cycle of destruction and construction has been put on repeat.

Few parts of the country are unscathed. Neighborhoods have been flattened, leaving Syrians stunned by the destruction with one-word comparisons: Stalingrad. Grozny.

Because families in Syria tend to be large and several generations often live together, the destruction of one building may leave more than a dozen people homeless.

Haizaan, in his early 60s, was born and raised in the three-story stone building in the Jabal Badro neighborhood. He lives there with 20 members of his family, including three children and their spouses and 13 grandchildren. His youngest granddaughter was a day old when the missile struck.

Jabal Badro was the first neighborhood in Aleppo to be struck by a Scud missile, on Feb. 17, residents say. Even Syrians who had grown accustomed to shelling and airstrikes were shocked by its pulverizing power.

Haizaan stood on the top floor of his home and pointed out all the reconstructed parts, including an extra layer of concrete to strengthen the walls. The rectangular outlines of bricks are now hidden beneath a coating of flimsy concrete that would do nothing to withstand a shell but gives the inhabitants some measure of comfort nonetheless.

“In case another one falls,” Haizaan explained. “If another powerful missile hits us, at least the house won’t entirely fall on top of the children.”

The previous night in a nearby neighborhood, a surface-to-surface missile struck several closely built homes, tearing a large path through them and making the structures unrecognizable; bunches of metal rods were twisted around one another like stiff, fallen streamers.

The rocket struck at dusk as families were sitting down to break the daylong Ramadan fast; more than three dozen people were reported killed.

Residents dug through the rubble into the morning hours, pulling out the bodies of neighbors and family members.

“We got used to it,” Haizaan said, the sound of shelling in the distance reinforcing his point. “Every day there are a thousand shells.”

**

Muhammad Mustafa Ali, 61, never considered leaving his home, even after a Scud missile landed a couple of blocks away, obliterating an entire block of homes. The force of the attack destroyed the second floor of his home, where Ali’s two sons and their families lived, as well as the front two rooms on the first floor. (No one was badly injured.)

Days later they began rebuilding the walls of the front rooms. Metal rods still stuck out overhead, now covered with a UNICEF tarp. The tarp, he said, was the only aid his family had received.

“We rebuilt this wall, but we are afraid it will get destroyed again,” said his son Mustafa Ali, 32.

“We are afraid of its sister,” his father added, referring to the Scud missile.

A few homes down, their neighbor Umm Noor invited a stranger into her house to give a brief tour of the DIY repairs she and her husband did to make the house livable.

A few weeks before, the family had applied to be admitted to a refugee camp in Turkey. But when the approval finally came, Umm Noor decided against leaving.

The couple, who have four young children, could not afford to hire anyone to make the repairs, so they bought two bags of cement and went about it themselves.

Large cracks in the white walls are now covered in streaks of gray cement. Concrete blocks cover blown-out windows, keeping everything out, including the sunlight.

Abdulrahim was recently on assignment in Aleppo.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.