Column: We live in Mike Davis’ L.A. — but not the one you think

As someone who has read most of Davis’ work and knew him personally, I can say that his writings were cris de coeur more than lamentations. He was less Jeremiah and more John the Baptist, preparing the way for who would ultimately save L.A.: Us.

- Share via

Hellish wildfires. Whiplash weather. Destructive winds. Debris flows. Torrential rains accenting punishing droughts.

Welcome to the Los Angeles Mike Davis predicted.

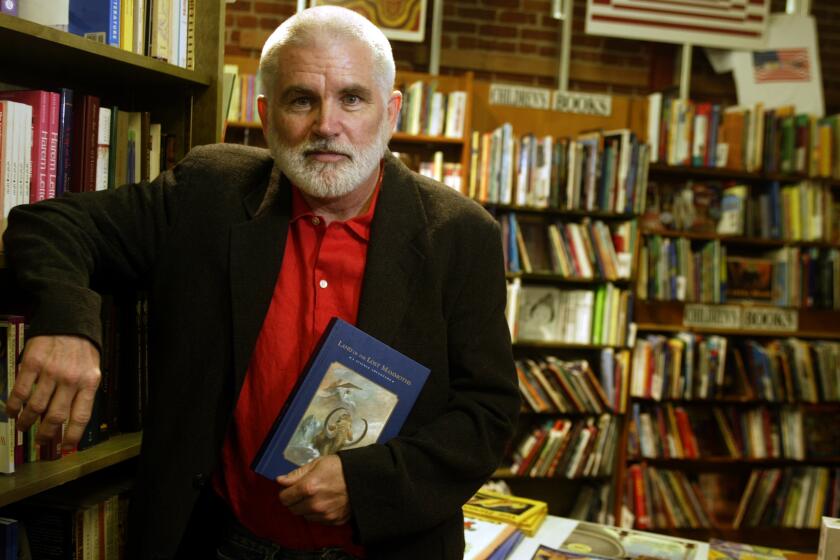

The late urbanist first made waves in the 1990s for forecasting an L.A. that would be one ecological and manmade disaster after another. His work quickly made him controversial among civic boosters, who dismissed him as a negative nabob who didn’t want the city to thrive.

Today, Davis is one face on the Mt. Rushmore of L.A.’s prophets, alongside Joan Didion, Carey McWilliams and Octavia Butler.

His words, more than anyone else’s, have been cited by writers and pundits across the world in this annus horribilis where nothing seems to be going right and everything seems to be getting worse.

The influential author scrapped boosterism for a dimmer view of a city shaped by developers, politicians and a militarized police force.

With respect to his fellow titans, none of them ever assailed the poultry industry for bragging about reaping “profit from the influenza-driven restructuring of global chicken production.” That’s exactly what Davis wrote in a 2006 book warning about the threat of avian flu, complete with a photo of a menacing white rooster on the cover.

Davis is the man of the moment, the person whose work all Angelenos should parse like a secular Talmud — but his premonitions of hellfire and brimstone aren’t what we should heed most.

The rest of the nation has eagerly waited for Los Angeles to collapse into tribal warfare and anarchy the moment a mega-catastrophe happened. If ever there was a time for that, it would be now, after the Palisades and Eaton fires.

While local political leaders have mostly fumbled or squandered the moment, it’s regular folks who have risen to the occasion. They have raised hundreds of millions of dollars for recovery efforts via everything from benefit concerts to donation jars at restaurants. Volunteers continue to clean up burn areas and gather supplies, with the promise to fire victims that they will not be abandoned.

Welcome to the Los Angeles Mike Davis wanted.

As someone who has read most of Davis’ work and knew him personally, I can say that his writings were cris de coeur more than lamentations. He was less Jeremiah and more John the Baptist, preparing the way for who would ultimately save L.A.:

Us.

“Although I’m famous as a pessimist, I really haven’t been pessimistic,” Davis told me in 2022, the last time we saw each other, months before he died of esophageal cancer at 76. “You know, [my writing has] more been a call to action.”

To cast him as an apocalyptic wet blanket is a disservice to a writer remembered by friends and family as all heart — a man who had faith that while L.A. would eventually go up in flames, it would emerge from the ashes stronger than ever.

“Mike hated being called a ‘prophet of doom,’” said Jon Wiener, a retired UC Irvine history professor who hosts the Nation’s weekly podcast and was a co-author of Davis’ last book, “Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties.” “When he wrote about environmental disasters, he wasn’t offering prophecy — he was reporting on the latest in climate science, and considering the human cost of ignoring it.”

Even while he was writing “City of Quartz” and “Ecology of Fear,” Davis was picking away at “Set the Night on Fire,” which he invited Wiener to shepherd toward publication.

“He wanted to show that the young people of color of Los Angeles had played a heroic part in fighting for a more equal future for their city” as a way to teach a new generation of activists to not lose hope in even the most dire of times, Wiener said.

I asked Wiener what his longtime friend would say about post-fire L.A.

“While hundreds of millions [are] being raised to rebuild big houses in the Palisades and Altadena,” Wiener responded, Davis would remind folks not to forget “the people who had worked there as gardeners, housekeepers, nannies and day laborers ... [who] are having trouble paying the rent and feeding their kids.”

Advocates gather to demand equitable fire recovery for longtime Altadena residents, immigrants and others

People packed a Pasadena church Friday to highlight the needs of domestic workers, seniors, renters and others who lost homes and jobs to the Eaton fire.

Thankfully, Davis wouldn’t have had to say that. The National Day Laborer Organizing Network, the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles and others have stepped up to help those affected, even as some of their volunteers have lost jobs and housing. Social media remains packed with fundraisers to buy new equipment for gardeners, patronize food vendors and find jobs for the unemployed.

Such efforts bring comfort to Davis’ widow, Alessandra Moctezuma, and their son, James Davis. In a phone call from their home in San Diego, the two told me how they’ve grieved the tragedy in L.A. from afar.

Moctezuma attended Palisades High and hiked above Altadena with Davis while he was writing “Ecology of Fear” in the mid-1990s. On social media, she saw photos of her alma mater in flames, posts from friends who lost everything in Palisades and videos of hills burned beyond recognition.

“He loved it up there,” she said, remembering that they lived in Pasadena, just seven minutes from Eaton Canyon. “I was already feeling all the emotions from that, and that’s when people started sharing Mike’s articles.”

She and James are grateful that people are citing Davis as a way to cope with the calamities of the past month — but the two urge readers to go beyond his best-known quotes and works.

“The problem is a lot of people misinterpret a lot of my dad’s work as schadenfreude, when it’s really not,” James said. The 21-year-old feels his father was, above all, trying to warn about the dangers of unchecked development, especially in more recent writings.

In the pages of the London Review of Books and the Nation, Davis tracked how California had changed during his lifetime, from a state with a wildfire season centered mostly on wilderness areas to one where the menace of conflagrations is year-round — and everywhere.

James recalled a 2021 documentary in which a gaunt, gravelly-voiced Davis told an interviewer, “Could Los Angeles burn? The urban fabric itself? Absolutely,” over shots of burning suburban tracts that looked eerily like what happened in Altadena and the Palisades.

“He talks about not just the possibility but inevitability about how there could be a giant fire burning down Sunset Boulevard,” James said. “That’s exactly what happened.”

With his love for Southern California and its people, Davis would “be happy to see all the mutual aid happening,” James said. “That’s the kind of stuff he advocated for.”

Moctezuma, an artist and curator, agreed. Her students at Mesa College filled four big U-Hauls with supplies and drove to Pasadena.

“Just seeing everyone sharing, that’s one of the things Mike always talked about,” Moctezuma said. “The kindness of people and importance of organizing — and the next step is organizing ourselves to help ourselves.”

She recounted one of her late husband’s favorite Irish proverbs: Under the shelter of one another, people live.

“I’m sure he’d have a lot of things to say right now,” Moctezuma continued. “He’d probably start looking into all sorts of things — the response from firefighters and politicians, regular people. Everyone would be interviewing him.”

Then she got quiet.

“He’d be heartbroken to see everything burnt down. And if his health was good, he’d be up there helping.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.