Would you want a big wind or solar farm in your community? We took a survey

- Share via

This story originally published in Boiling Point, a newsletter about climate change and the environment. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

In last Thursday’s Boiling Point newsletter, I posed two questions: If you wouldn’t want to see a solar farm, wind turbine or power line in your backyard, what would it take to change your mind? And what, if anything, could private companies or government agencies do to make the renewable energy infrastructure a worthwhile trade-off for you?

Thanks very much to the nearly 150 people who filled out our survey, and the many more who emailed their thoughts. Your responses were almost uniformly thoughtful and constructive. I read them all and want to share a few takeaways.

First off, I was struck by how strongly many of you feel that rooftop and community solar systems in urban areas — on homes, parking lots, warehouses and more — are the only truly sustainable clean energy technology.

As Glendale resident Willard G. wrote, “Solar farms could go up en masse on rooftops of every community in Southern California.”

“There’s nothing more degrading to the environment than the thousands of warehouses sprouting like weeds, particularly in the inland communities,” Willard G. wrote. “There isn’t one square inch of their rooftops that shouldn’t be covered with solar panels. Every urban panel means one less square meter of pristine desert landscape torn up for solar development.”

I hear similar arguments all the time, so I wasn’t especially surprised. But I was also intrigued by how many folks pushing rooftop solar didn’t outright reject large solar and wind facilities on public lands. Instead, they said those lands should be developed only after all the available rooftops, parking lots and other infill space within cities is exploited.

“Maybe put up solar to shade the freeways,” Patrick W. suggested. “If that is still not enough, then we can talk about converting natural habitat to solar farms.”

Survey respondents cited all sorts of reasons for being skeptical of large solar and wind farms, including environmental damage, visual impacts, noise levels and dust emissions during construction. They also proposed a variety of alternatives, such as using less energy overall — or building nuclear power plants that take up less land area. To the extent that big solar and wind farms are still needed, they urged improved recycling of equipment to make those projects more sustainable.

Some rooftop solar proponents went further, calling for a fundamental overhaul of the energy industry to limit the dominance (and profits) of large utility companies. Rooftop solar panels, they said, should be made much more affordable, if not free — a major shift from the current situation in California and other states that have slashed solar incentives.

“Big Energy is the cause of climate change, and Big Energy in sheep’s clothing will never be the solution,” Sheila B. wrote.

Others said they would embrace big renewable energy facilities in their communities — or at least tolerate them.

Richard S. spoke for many survey respondents by describing NIMBYism — the anti-development “not in my backyard” attitude — as “selfish and immoral” and in the context of worsening climate change. Texas resident Kristin H. was even blunter, dismissing concerns over not wanting to look at solar and wind farms with the comment, “Visuals matter less when you’re dying.”

Or as Denny R. wrote, “Every community should be open to this. If not in our backyard, then where?”

Some renewable energy supporters were more measured, describing large-scale projects as a necessary sacrifice, with downsides but greater benefits. Maguire M. wrote that while they find wind turbines unattractive, “I’d be OK with it if it helps improve the environment.” Bay Area resident Judith K. had a similar perspective about the region’s parks and preserves.

“While many would fight to the death to keep them open space, I would be willing, for the survival of the planet and of us, to contribute some of that space for the cause,” they wrote. “The wind farm would have to be safe for birds, and neither that nor solar could block the trails wildlife use to move around.”

Simon K. took the “sacrifice” mentality even further, saying we should approach the battle against global warming “with the same single-minded focus the Western alliance member countries marshaled in World War II.”

“All segments of society should be enlisted to make sacrifices and participate in this effort to combat a threat every bit as dangerous as the fascist regimes of the last century,” they wrote. “Our parents and grandparents collected scrap metal and newspapers, bought war bonds and donated their tires, living by the motto, ‘Make It Do, or Do Without.’ We need to mobilize patriotic citizens, young and old, from every country to fight this existential threat.”

Much to my delight, many people shared ideas for what might make rural communities more likely to support solar or wind farms in their backyards — which was the main point of the survey, after all.

Jo L., for instance, said they’d be more likely to support a solar farm in their community if it was “surrounded by high vegetation” to reduce visual impact. They’d be more likely to support a wind farm if the turbines were “non-contiguous” along the horizon, so that it was possible “to see a partial stretch of wind farm, but not only wind farm, when looking at a view.”

Other survey respondents said it will never be enough for rural towns to know they’re helping tackle climate change — they need to see local benefits from renewable power projects, not just supply electricity to far-off population centers.

Several people said towns adjacent to solar and wind farms should be offered free or low-cost electricity, or be given batteries to help them store clean power for after dark. One rural resident called for an end to California’s property tax exemption for solar developers — a subject of controversy in Sacramento. Another said they’d support clean energy in their town but would want to see financial support for homeowners whose property values might be negatively affected by a solar or wind farm.

Some folks said developers should be required to fund local schools, public parks and other community priorities.

Lana M., for instance, wrote about living in the rural high desert in the 1990s, and the senior center’s role as a community hub for their small town. The building was used for holiday parties, picnics and water board meetings, but it fell into a state of decay.

Ongoing funding from renewable energy companies, Lana M. said, could help to maintain those kinds of facilities.

“Even giant [one-time] piles of money are not enough,” they wrote.

Orange County resident Debbie S. was one of several respondents who mused about direct payments to rural residents. As an example, they pointed to the Alaska Permanent Fund, which distributes royalties from oil extraction to all Alaskans.

“It is the people in the region/county who will lose the open space and views when large installations are built, and it is the local ecosystems that will suffer,” they wrote. “There should be significant and ongoing tangible compensation as a benefit to offset the losses. ... I also think it would make people more ‘invested’ in the success of renewable energy.”

Not everyone is going to be swayed by money, though. One rural Sacramento County resident, Daniel P., said they would support a local renewable energy project only “if it minimized environmental impact and was cost efficient.”

“I would not expect the project to eliminate all environmental impacts or provide unrelated ‘benefits’ to our community,” they wrote. “Too often ‘benefits’ are simply bribes paid in the permitting process that needlessly add to ultimate energy costs.”

What about more transparency? Eli S. suggested solar and wind developers “produce a packet of information that describes the trade-off being made” — how much energy will be generated, which wildlife species will be affected, how much fossil fuel the new facility would displace, etc. That kind of information is typically buried in dense, difficult-to-parse regulatory documents.

“Have it approved by some science research group that isn’t biased. Make the community feel more involved,” Eli S. wrote.

Others suggested that growing local support for clean energy could be as simple as better listening.

“The best way to find out what a community would want from a development or conservation is to ask them,” Dave M. wrote. “Listen more to the younger people than the older people — older rural people don’t care about climate change because they won’t be around to experience it. But their kids will.”

Shared responsibility was another theme.

“Force urban centers and suburbs to build out and pay for solar and wind assets located in their backyards first. Make it fair, make them deal with the pollution, eyesores, noises, land being seized, etc.,” rural resident Stephen V. wrote. “Then after they have sacrificed their peace some, we’ll consider it out in flyover country.”

On the flip side, at least one urbanite wasn’t sympathetic to the concerns raised by renewable energy skeptics.

“Minimizing climate change and its associated horrors — mass death from heat, famine, war, societal breakdown, extinction of millions of species — is obviously good for everyone,” Daniel M. wrote. “It’s beyond idiotic to talk about needing to hear additional specific benefits locally.”

Maybe that’s the case — and maybe it doesn’t matter. The reality is, American democracy gives local governments and the courts all sorts of power, meaning opposition to renewable energy can — and has — blocked badly needed projects.

If rural residents don’t want solar and wind farms in their backyards — or homeowners associations see rooftop solar systems as eyesores — then the burden shifts to the rest of us to take those concerns seriously and decide how best to respond.

Several survey respondents framed the problem in a more hopeful light.

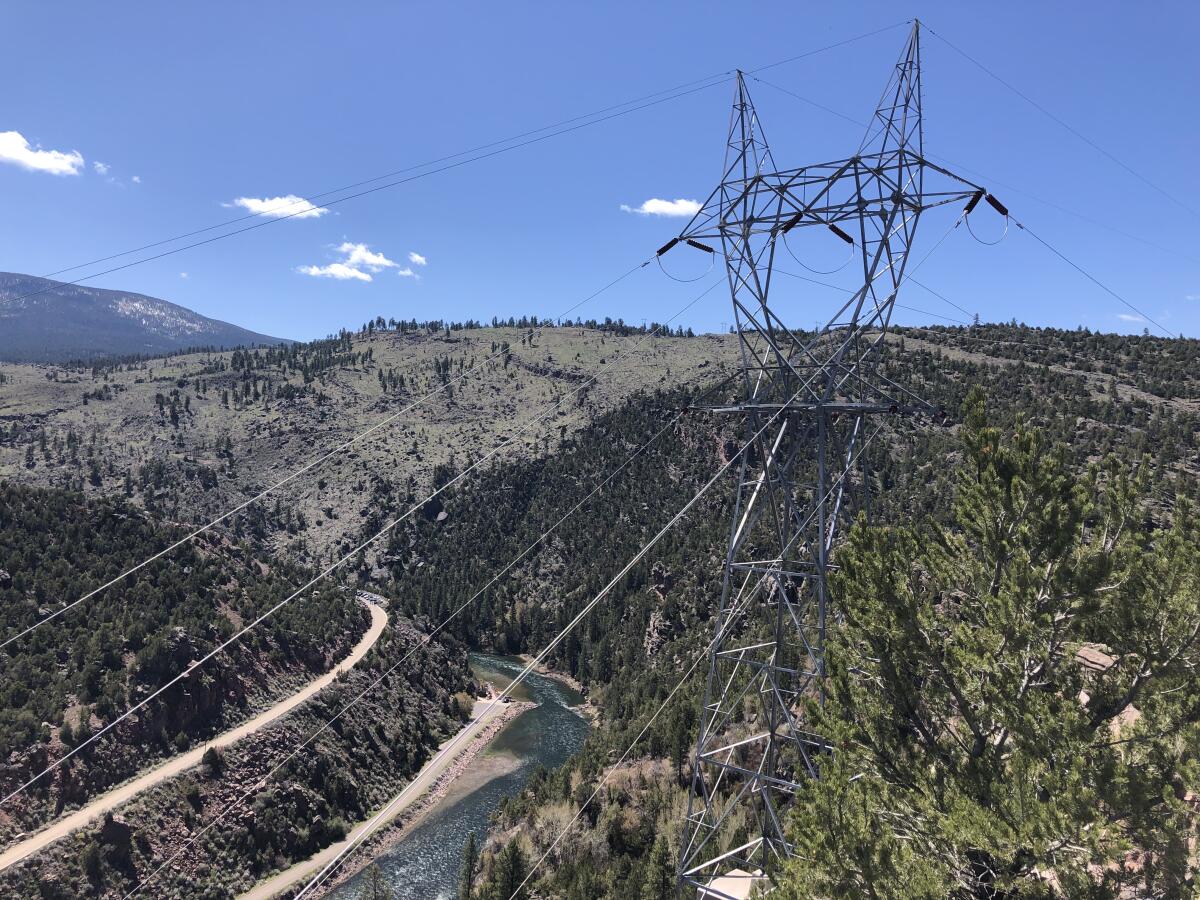

Orange County resident Michael S. said they’d be “proud to see both solar installations and those beautifully sleek, white wind towers from my living room windows,” knowing that less fossil fuel is being burned as a result. Gary S., meanwhile, was one of several individuals who said renewable power plants are a lot nicer to look at than traditional energy infrastructure.

“People have gotten used to seeing transmission lines and towers, refineries and oil wells everywhere,” they wrote. “These are way, way more unsightly than flat fields of solar panels, or gracefully spinning wind turbines. Once in place, these would quickly become accepted as a normal sight.”

David W. talked about putting up rooftop solar panels and adjusting to the aesthetics.

“When first installed both my wife and I looked at the house and said, ‘That’s pretty ugly.’ A week later we didn’t even notice,” David W. wrote. “This infrastructure will become the new normal if we just get going.”

Other survey respondents suggested all sorts of middle-ground ideas: putting solar panels and wind turbines on farmland or industrial sites, redesigning projects to better accommodate wildlife, starting with private lands before developing public lands. I’ll have more in-depth reporting on those types of ideas in future installments of our Repowering the West series.

Thank you as always for reading, and for moving this conversation forward with me. More to come.

ONE MORE THING

My L.A. Times colleague Alex Wigglesworth wrote this week about a new peer-reviewed study finding that 37% of the forest area burned by wildfires in the American West and southwestern Canada since 1986 can be traced to climate pollution from just 88 fossil fuel companies, cement manufacturers and current or former centrally planned states.

Here’s Alex’s story. And because we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that specific companies are responsible for the climate crisis, here’s an alphabetical list of all 88 entities, courtesy of the Union of Concerned Scientists, which produced the study:

- Abu Dhabi National Oil Co.

- Alpha Natural Resources

- Anadarko

- Anglo American

- Apache

- Arch Coal Co.

- Bahrain Petroleum Corp.

- BG Group

- BHP Billiton

- BP

- British Coal Corp.

- Canadian Natural Resources

- Cemex

- Chevron

- China

- CNOOC (China National Offshore Oil Co.)

- Coal India

- ConocoPhillips

- CONSOL Energy

- Cyprus Amax

- Czech Republic

- Czechoslovakia

- Devon Energy

- Ecopetrol

- Egyptian General Petroleum

- EnCana

- ENI

- Exxon Mobil

- Former Soviet Union

- Gazprom

- Glencore

- HeidelbergCement

- Hess

- Holcim

- Husky

- Iraq National Oil Co.

- Italcementi

- Kazakhstan

- Kiewit Mining Group

- Kuwait Petroleum Corp.

- Lafarge

- Libya National Oil Corp.

- Lukoil

- Marathon

- Murphy Oil

- Murray Coal Corp.

- National Iranian Oil Co.

- Nigerian National Petroleum

- North American Coal Corp.

- North Korea

- Occidental

- Oil and Gas Corp., India

- OMV Group

- Peabody Coal Group

- Pertamina

- PetroChina

- Petroleo Brasileiro (Petrobras)

- Petroleos de Venezuela

- Petroleos Mexicanos (PEMEX)

- Petroleum Development Oman

- Petronas

- Poland

- Polish Oil & Gas Co.

- Qatar Petroleum

- Repsol

- Rio Tinto

- Rosneft

- Royal Dutch Shell

- Ruhrkohle AG (RAG)

- Russian Federation

- RWE

- Sasol

- Saudi Aramco

- Singareni Collieries Co.

- Sinopec

- Sonangol

- Sonatrach

- Statoil / Equinor

- Suncor

- Syrian Petroleum

- Taiheiyo

- Talisman

- Total

- UK Coal

- Ukraine

- Vistra / Luminant

- Westmoreland Mining

- Yukos

We’ll be back in your inbox on Tuesday. To view this newsletter in your Web browser, click here. And for more climate and environment news, follow @Sammy_Roth on Twitter.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.