- Share via

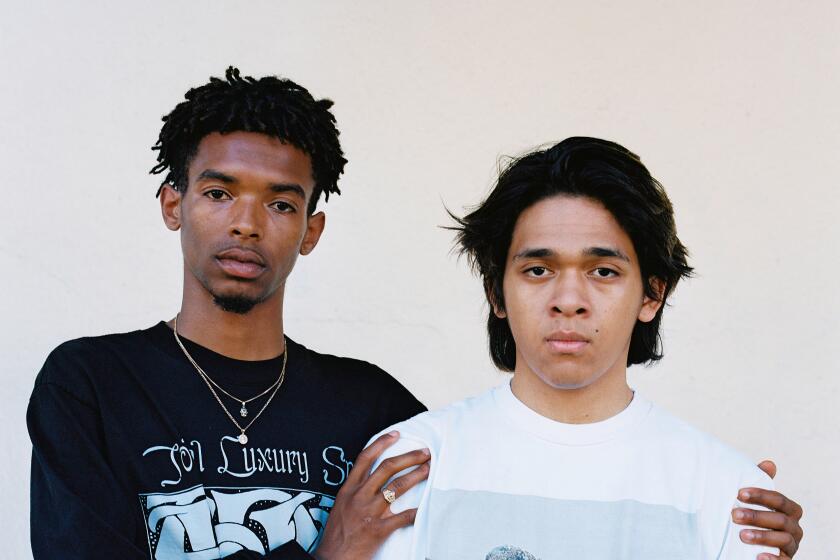

If you haven’t yet heard of Little Tokyo Table Tennis, also known as LTTT, chances are you’ll now start noticing it everywhere. The table tennis club in the Little Tokyo neighborhood of Los Angeles, held at Terasaki Budokan every Tuesday evening, is more than a sports club — it’s an expansive network of hundreds of people, both young and old, and it’s also a fashion brand. Jiro Maestu, LTTT’s founder, is the designer behind the table tennis-inspired merch, including caps, jerseys, pants, bags, socks and paddle covers (prior to LTTT, Maestu designed whimsical, sculptural hats for his other brand, Poche). His hope? To shift “the mentality of what ping pong can become.”

In this conversation, Sonya Sombreuil, designer and founder of streetwear brand Come Tees, sits down with her friend Maestu to get the backstory on how LTTT came to be and how it’s exploded into this “unspoken but blatant community.”

There is no normalcy to the clothing artist Sonya Sombreuil makes. She is moving at her own speed.

Sonya Sombreuil: LTTT recently celebrated two years. Could you tell me about how it’s evolved since the start?

Jiro Maestu: Well, the brand has become this force of hundreds of people.

SS: Do you consider the people that attend your programming a part of the brand?

JM: I would say so. I’m making the decisions with “x” amount of other people, but I consider myself a part of the brand as much as anybody else that wants to engage with it.

SS: Is it almost like a collective?

JM: It’s a table tennis club first and foremost for me. Anybody that comes becomes a part of the club. I go on Tuesdays, so I’m a part of the club. That’s really how I want to consider it.

There’s a classic feeling to L.A.’s favorite regalia that transcends genre and class. Every time you freak it, you step into a high-fashion world that is all your own.

SS: I was thinking earlier about how I perceive LTTT, and I realized it has an element of paradox. You have this hypnotic logo that is easily recognizable, but it’s also very veiled and accessible at the same time. From the internet, you can’t tell what’s going on. It’s really an invitation to show up in person to understand what the f— is happening. But I love that — the fact that it’s super pop, super available and also confusing, mysterious.

JM: I guess some people wouldn’t know that it’s a real club; Little Tokyo is a small community. I’ve had homies tell me when they’re traveling around the world, they’ll go up to someone with an LTTT hat and go, “Oh my god, you know LTTT!” And it’s often met with, “No, I do not know what this is.” That happens a lot.

SS: Right now, with a lot of brands, there is this parlance around identity and community but it’s totally about selling the product. I think there is a real resistance to that in the way that you present your product.

JM: I’m not inventing anything, which is a state of mind that I’ve matured into. I used to always want to feel as though I’m doing something that’s never been seen before, whereas now I am obviously conscious that anything I am doing is a regurgitation of something else. Since I happen to be dealing with a sport that’s rather niche in America, I’ve found the freedom to reinterpret that with my own perspective. Everything I’m doing is adding into this conversation.

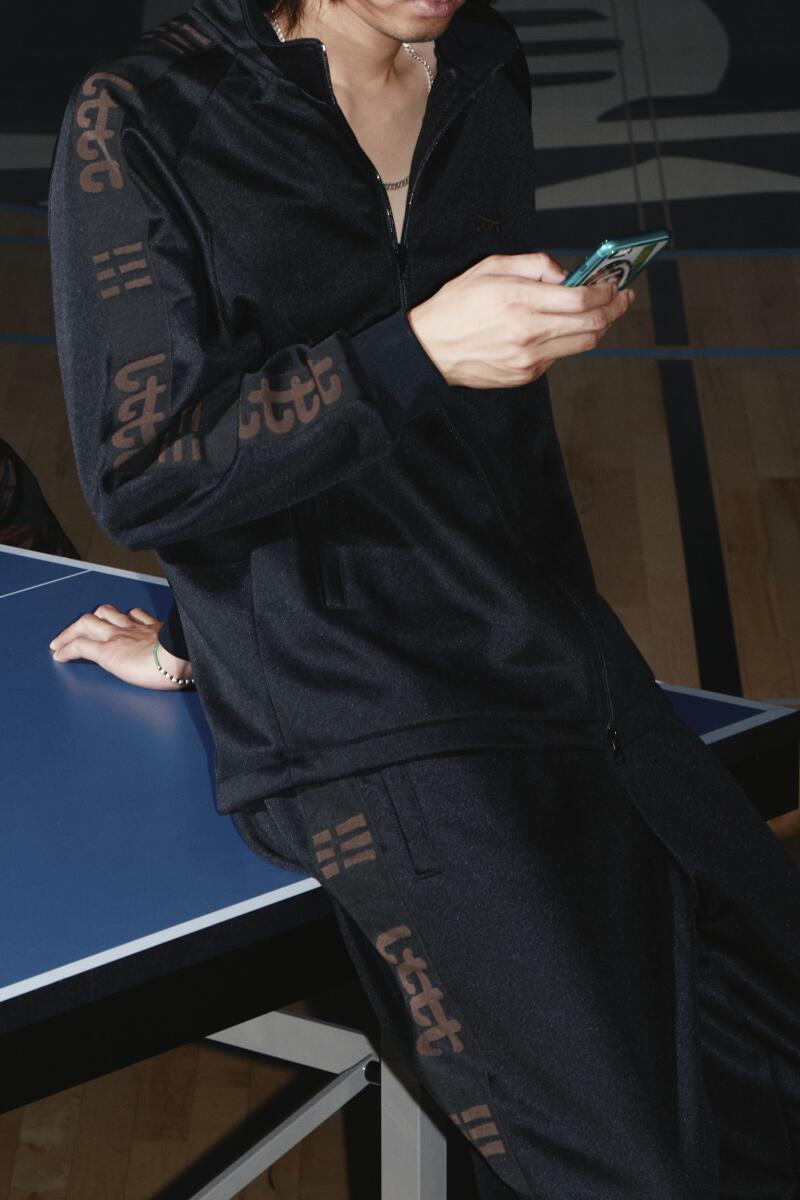

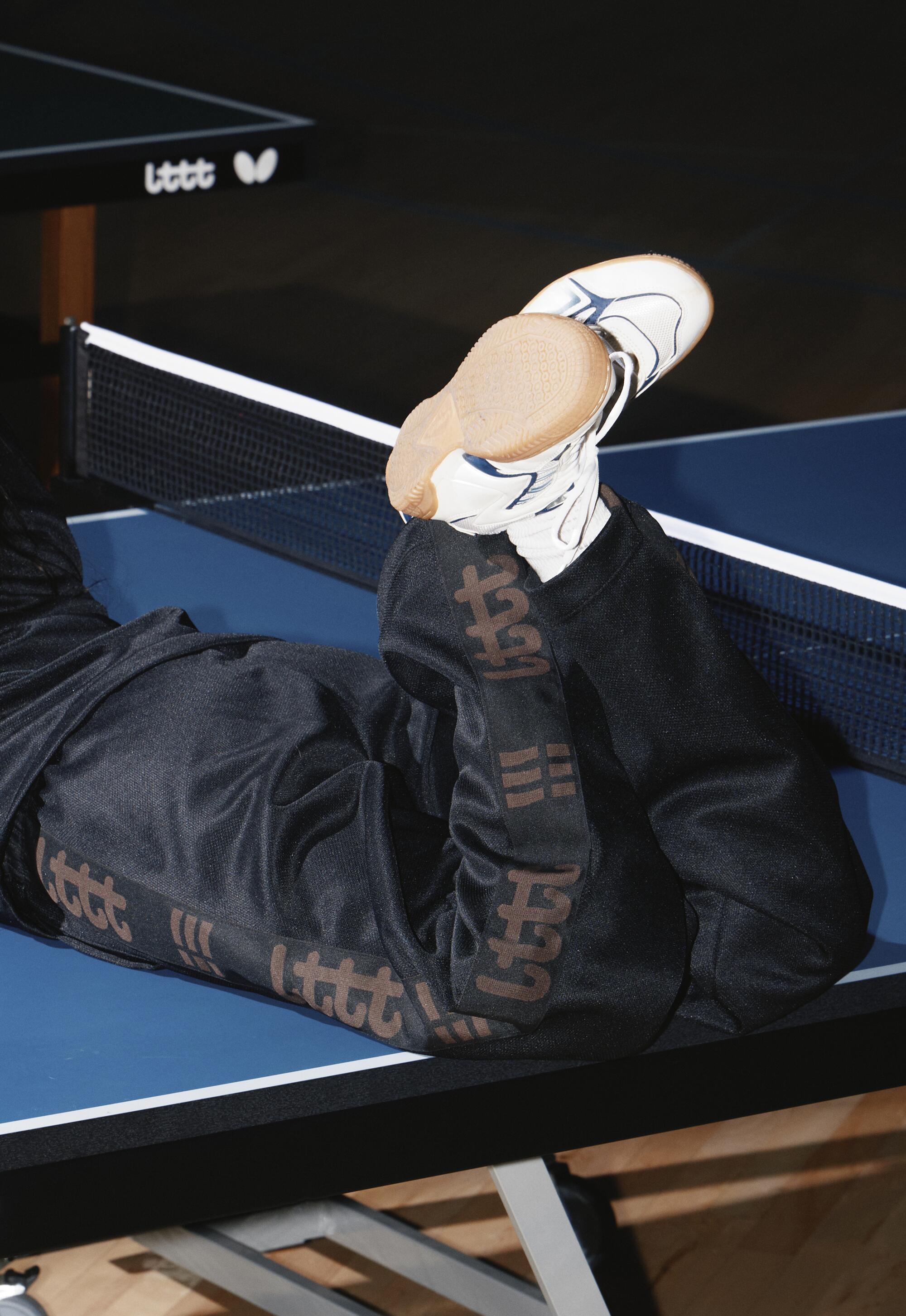

LTTT tracksuit in black; “I was very hellbent on having that one logo you can just put everywhere,” says Maestu. LTTT tracksuit in black (left) and LTTT bag (right). (Angella Choe / For The Times)

SS: The jerseys that you just released are recycled, right? It’s like a legacy project.

JM: I’m selling a product through the club, but the jerseys have so much information and culture tied to them — that’s the angle, for me, beyond the product. When you buy this or you want to look up the original brand of the jersey, you’ll find out tons of information about the sport that you inadvertently participated in just by being attracted to the product that I’m presenting.

SS: The way that apparel relates to sports is so different.

Daniel DeSure’s brand and the artist community behind it are pushing the possibilities of communicating through graphics on clothes.

JM: It’s different but also the same. Because even in the industry of table tennis, you automatically begin to think, “Who am I? What kind of athlete or participant am I going to be?” Am I going to be like, “Oh, these brands are wack,” or “These are cool” — or these are the ones that were cool, so I’m only going to reference the stuff they made from 20 years ago. That’s what is so fun for me as a designer because I get to make those decisions. Of course, I’m pedaling my point of view with this sport.

SS: Could you say a little bit more about your point of view about this work?

JM: Table tennis has a pretty kitschy identity in the U.S. Superficially, you’ll see a ping pong table at a summer camp or at a frat house. People think it’s mini tennis, it’s cute. What we’re doing in Little Tokyo, as Asian Americans, is reappropriating table tennis. For the younger generations, a big aspect is bringing over a culture that is huge in Asia and translating that and giving our own perspective here. We also feel a tie to it — it’s like our identity in a way.

SS: Is LTTT intergenerational?

JM: There is a really wide age range. Over the past year, because it’s accessible and it’s playful, there’s a lot of really young kids, like some high schoolers. We’ve helped these high schoolers start their own ping pong club at their school because they wanted to have their own version of what we do. That’s what is actually going to change something like a sport. Every sport that wants to be reinvigorated or do something important starts with the younger generations. We also have seniors that have their own club and play three times a week using our equipment. Right now, we have anywhere from 16 to 50 year olds that come on Tuesdays.

SS: In reading one of your past interviews, on the subject of sustainability, you said that it hurts to make new things.

JM: It always hurts to make anything. A lot of brands make so much s—, pushing the sustainability rhetoric, but 90% of the things produced just feels like … why? Just don’t make it at all. But I think about that all the time. I don’t have an answer for sustainability other than just stop making s— altogether.

SS: There are ethical arguments for everything at this point, but I resonate with that. There is a part of me that internally shudders every time I buy 1,000 shirts. Yet I love making things. It is cool that you repurpose.

The Taiwanese American artist’s designs are an antidote for a textile industry status quo that just talks the talk.

JM: I’m repurposing on such a small scale, still, that it feels almost inconsequential. If I could only repurpose, I would, but there is a finite amount of [jerseys]. We only release 20 at a time. I’m not capable of doing more because I have to find them one by one.

SS: How did you come up with the LTTT logo? It’s such a compelling logo.

JM: I got lucky. It would be completely different if this were in Koreatown or the San Gabriel Valley — we have three of the same letter. I was researching a lot of logos because the graphic design in Japan and specifically around table tennis is very distinct. It was a lot of research about table tennis brands, what their logos are — what companies are sponsoring them, how they place their logos on jerseys. The Japanese national team is sponsored by Zen-Noh, which is an agricultural conglomerate, and their logo is a simple but strong oval with the characters inside. And I thought: It needs to be strong and unchangeable. I was very hellbent on having that one logo you can just put everywhere.

SS: It resonates with me, coming from a DIY, punk or underground music background, that to be a participant all you have to do is show up. But having the curiosity and being compelled to show up is a big deal. I feel people don’t necessarily have that in the ways that they used to. LTTT is beckoning, open and invitational.

JM: It is something that wouldn’t exist without its counterpart. The brand is only there as a commodity to prove that you are a part of it.

SS: A souvenir.

JM: We’ve nurtured this feeling among participants that by having these things they really are a part of this. There is an understanding between people who own things; they see each other on the street. I hear this all the time — people will lock eyes that have hats on. It’s an unspoken but blatant community.

Smart fashion is not about an aesthetic. The brand once called a cross between Comme des Garçons and Levi’s knows that it’s about putting something extra on it just for you.

SS: A subworld. It’s like when you’re into a band that not a lot of people know about — to have the gear means you showed up.

JM: You showed up or you know someone; there is a connection. That’s what makes the whole thing work.

SS: How do you intend to hold onto that as you grow?

JM: What’s going to help us retain this feeling is that firstly we are a club in Little Tokyo and every week we do this thing. That’s what keeps us on the ground and for the community that we’re serving. We’re activating a space that is a community center. It should never go away, and I don’t think it will, no matter how we grow elsewhere.

SS: Come Tees is a difficult project because the aesthetic is so me and I am always compelled to make things that can be difficult to wear. There can be a sort of exclusivity to that, but I love the anti-hype quality of a low bar to entry — all you have to do is come. And so much fashion is the inversion of that.

JM: That’s definitely something that I am still new to, but I am loving every moment of what it is and becoming. I’m sure it can be a different experience for other brands as the idea can often be, “Let’s get this s— on as many people as possible.” Whereas this is more of an organic growth. But it comes after having done what you’re doing — I love that also about design and fashion.

SS: My introduction to you was carrying your hats at [my shop] Classic Hits. That was an insane, weird, eccentric thing. Each hat was different. People would hit me up all the time from all over the world asking for them since there was such a limited amount. And this speaks to your sensibility and ability to communicate. Your products are polarized in a way — you have the LTTT hat and the Poche hat — but they have a similar charisma.

JM: I’ve come to realize that I really love the marketing side. Obviously, I really love making things but sometimes that only goes as far as the way you’re able to present something. I was getting really into it with Poche: How am I going to show this? What kind of image am I going to make out of this thing that I just made, which looks completely ridiculous?

SS: Is Poche still alive?

JM: Right now, not really. But it’s not like it disappeared. I found myself doing things that I didn’t really want to be doing. Because I started doing things with LTTT, I decided to stop and let Poche breathe. I want to find a time when I am really strong with LTTT and more financially stable to allow Poche to be what it needs to be. I’d rather not make any money with Poche and fully prioritize making things that truly mean something to me.

SS: You picked up table tennis during the pandemic, right?

JM: A year or two before, and then during the pandemic is when we got …

SS: When you got nasty?

JM: When we got nasty. We had a table at my mom’s house, where I was living during the pandemic.

SS: I’ve seen this legendary table.

Oversized is a lifestyle, not a trend for the brand from the San Gabriel Valley. Its designs are driven by the idea of feeling like you can grow, change and move around in clothing.

JM: I won it at a raffle at the Hammer Museum in 2014. The museum has all these ping pong tables on the mezzanine. They were raffling one off, and I won it. So, during the pandemic, my three friends and I would roll up to my mom’s house and play for 12 hours a day, every day, for a year. Around the same time, the Terasaki Budokan was opening. So, I asked them about ping pong, and they were like, “I don’t know if anyone really plays ping pong.” I said, “I swear, at least me and three others do; let me start this club.” They said sure, and there it is.

SS: It seems table tennis is coming back, living again.

JM: It’s living differently. I don’t know if it’s ever lived the way it wants to live in the U.S. because it’s always been alive in Europe and Asia. And it’s not that I want to make this American table tennis brand, we just happen to be in the U.S. My focus, the purpose, is to glorify Little Tokyo as a community. Because that’s where I am every day, where my family is from. I want to see this neighborhood be the s—. I do this for Little Tokyo to make sure this neighborhood is preserved and has, possibly, a new legacy.

SS: Table tennis is interesting — first of all, its status in the U.S. made it ripe for you to have a voice in it, but also, it’s a sport where you can be a casual member. You don’t need certain apparel; you can pull up. It makes sense to have a social club around that.

JM: That’s the fluke characteristic that not a lot of other sports have. It can be as casual or as serious as you’d like it to be. I see it all the time, people who come for the first time, I think because of my background and other projects ...

SS: Fashion people [show up].

JM: Yeah, people come through very fitted — heels, boots. They play, and they can totally do it and still have so much fun. But then they’ll come for three consecutive weeks, and by the fourth week they come in shorts. It’s funny to see. I love seeing people who show up for the first time and the people who have been coming for two years straight. At this point, we have a really tight knit community that is ever expanding. Some kids have really been there every Tuesday for two years.

SS: What a gift.

JM: It’s so fun. It’s a crazy liberty that we have to write a part of history with this sport that hasn’t really been developed in these ways that every other sport has. There is infinite space.

SS: Someone could start a rival club.

JM: I say that all the time! There should be — I don’t own ping pong. I feel blessed to be contributing to a part of it.

Sonya Sombreuil was born in 1986 in Santa Cruz, Calif. Alongside her painting practice she founded the Los Angeles-based fashion label Come Tees in 2009. She was featured in the Hammer Museum’s 2020 biennial “Made in L.A.”

Lettering by Jake Garcia / For The Times